Visiting Smile Foundation’s Mission Education (ME) center located at Shri J J Colony, Dhaula Kuan, New Delhi which doubled itself up as a tailoring-training center for the empowerment and skilling of community women in partnership with The Health and Care Society (a grassroots nonprofit) a few days ago, threw me back to my childhood days.

The extremely narrow lanes, the electricity wires hanging close by to our heads, a local ice cream vendor, and the unbearable smells of the open drainage, all led me back to a world I was a part of, for a long duration of my life.

My father was a migrant from a rural part of West Bengal who made Delhi his second home in the early 80s searching for a better life. Migrants always look for their communities or the proximity to them when they move places. The language, the food, the clothes— mainly the culture and its familiarities, is what one seeks to feel comfortable in their initial days of homesickness and alienation.

It shudders my heart to think of my mother, barely 15, when she was married off to my father being in a city that wears, walks, and talks differently. Till my early adolescent years, I saw her wearing taant cotton sarees whose stiffness was maintained by dipping it in hot rice water (a suspension of starch obtained by draining boiled rice or by boiling rice until it completely dissolves into the water) in a drape that I see alive only in remote pockets of Bengal now. It was a drape without pleats looking nothing like the graceful drapes of the lead characters of Devdas and Parineeta.

My parents started out with a small semi-furnished rented room in Beadon Pura, Karol Bagh wherein they made great, warmly fuzzy relationship with the owners of the house with their closeness peaking when one of them nicknamed me Guriya. Daknaams or nicknames are a big part of Bengali culture and your whole family— intimate and extended would know you by your Daknaam. You ever mention Hasina or Husnaara (the name prophesized by my mother for me) to them when speaking about me, and they will be lost, completely lost! Hasina, who?

My father worked hard (and, as I got to know later on, partied harder— making it tough on my very young mother) and soon he bought a building to himself floor by floor in the same gali (you don’t go by block numbers in semi-ghettoes; also, my permanent address is still this place). Every floor was a mere 25 Gaj (223 square feet) including staircase and alleyway spaces. The concepts of living, drawing, study, and master bedrooms all were alien to me till I developed an intense short time interest in architecture and read all about home layouts and their detailing.

There were no trees inside my gali, just one banyan tree outside the gali, on the main street (still there and standing proud). So, the frequent power cuts of the 90s and early 2000s meant sweaty nights with everyone out with their steel torchlights if they realized that the power cut is going to be a long one. Men would get into conversations of “value”— business, cricket, politics, and women would talk about their children, dinner menus, mayekas, with one saying “Hamare waha toh itni light nahi jaati.” (My mother’s place never sees such frequent power breaks); always eager to give up her belonging at her husband’s house when things got too inconvenient too often.

Some of the relationships soured over the years and some became steel-strong withstanding the harshness and the gentle days of life.

We were not poor. My father a goldsmith, and a bloody good one at that, made enough money for us to earn the ‘middle-class’ tag. But it was hard for my illiterate parents to get me admitted into a small private school that at most looked like a small hospital building of a Tier- 2 city but where I would spend the best years of my life and would also win one of my closest friends for life, Shalini. My father used jugaad and bribery to get my brother and me to become a part of the English-speaking world. What he wouldn’t know is that 99% of the students and even teachers there would be conversing only in Hindi.

Our house’s window opened up into another’s, that was at best two feet away. Privacy, ventilation, and the traveling of sunlight and wind were all concepts never understood with the times spent inside the home.

You will have to go to the bathroom to cry ugly in your teenage years. You will have to wait for the whole family to go to sleep to find some alone quiet time for yourself. Children surrounded by noise all the time crave quiet, quite badly.

You cannot invite friends over for night stays— not that Maa would have ever allowed that. You get used to taking small spaces inside your home and exhibiting peak imposter syndrome when in other spaces. You will witness your parents fighting because they cannot ask you to go to your own room and keep the door shut.

And, if you happen to witness violence, followed by showering of intense love, your idea of love will shape into something that will want and expect wars. Because blood is red, and oh, so attractive!

I never got a proper room to myself till 2013 (just fresh out of my graduation college) when we shifted to the rich locality of Karol Bagh densely populated by Punjabis. I was welcomed with ample sunlight, a big bed, all the modern furnishings, and a washroom whose floor was so perfect that I would spend many weekend afternoons lying on it because my friend that was a luxury that I hadn’t dreamed of, but came to my lap willingly, and I grabbed it— like a moth to a flame.

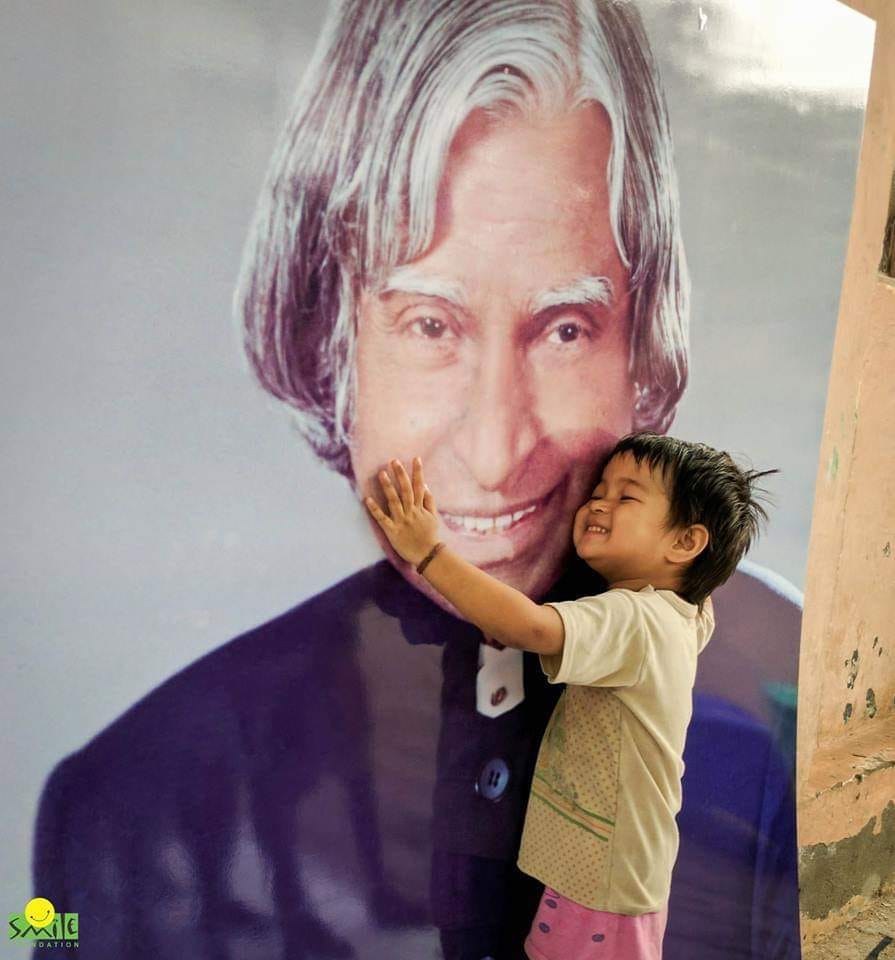

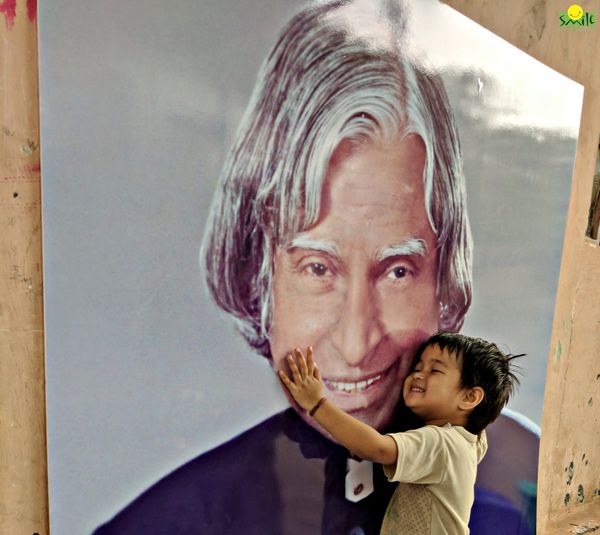

Entering Shri JJ Colony (the center’s location) and navigating its streets made me lose my breath for a few seconds. This area is an urban slum where most houses are less than 100 square feet in size. The children use the education center’s front space as their playing ground. They come to the place in the hope of getting an education, a place to camaraderie with their friends and to get refreshments that their daily-wage laborer parents cannot afford every day.

The time I spent there felt less like an education center and more like witnessing children hanging out with friends, settling scores, the older ones coying around their crushes and every such delicious wasteful indulgence.

A group of three girls made a circle to hear the story of one of them who had something urgent to share. As I pulled myself out of their world, remembering that privacy should be made space for in public spaces too, I think of this country’s unchanging apathy, disregard, and indifference in terms of housing disparities. The news of Vienna’s 80% population being eligible for public housing adds salt to the wound.

Looking out of my small balcony attached to my room in my newly rented space overlooking a banyan tree, I am confident that no person should be living in slums. That cheap labor is what is going to make this country remain poor. That living in the margins is not by destiny, but by design.

And finally, that inaction is never an option when our fellow humans are suffering every day.