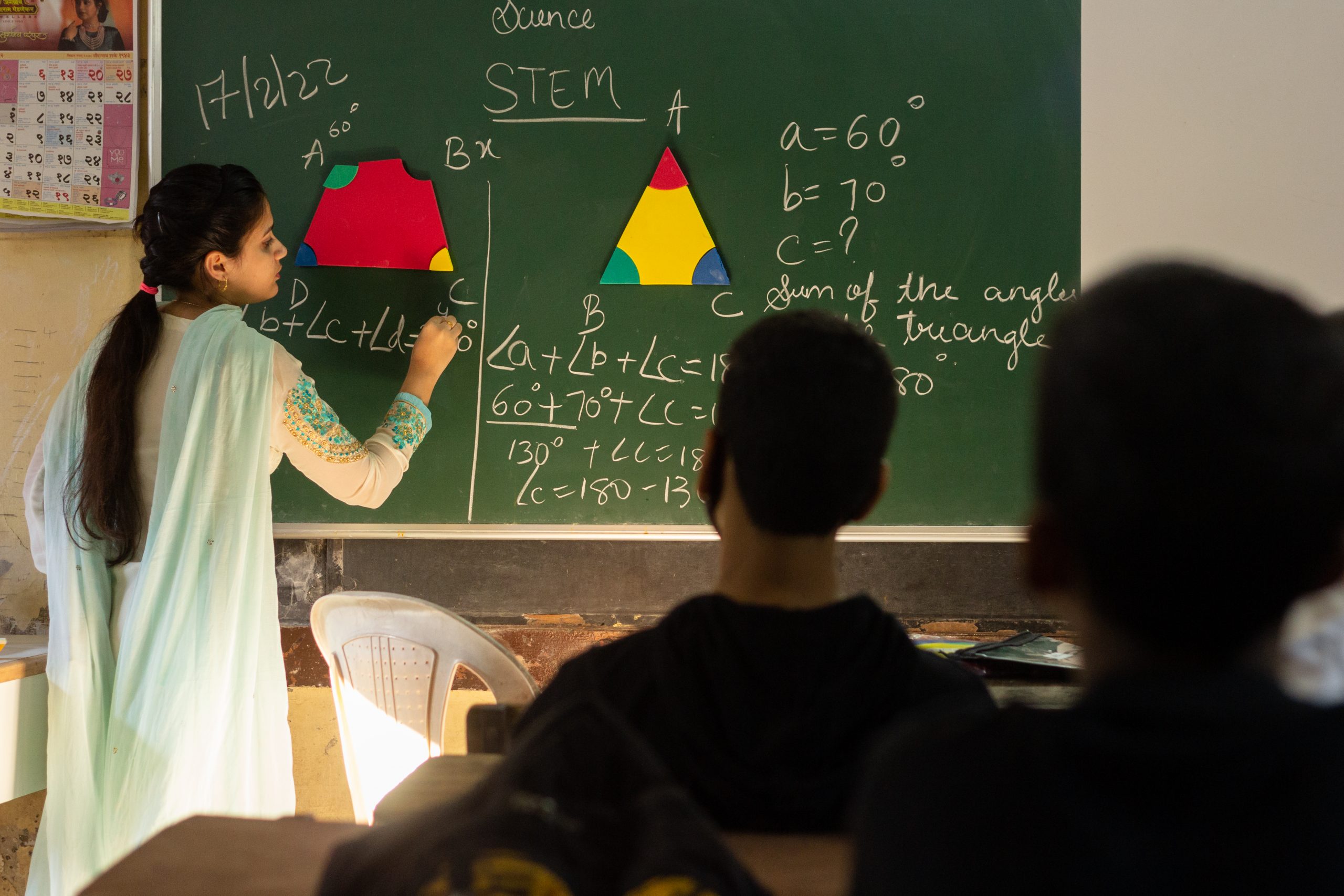

In a government school classroom in Siddharthnagar, eastern Uttar Pradesh, a group of Class 7 students cluster around a simple experiment. There is no laboratory, no expensive equipment. Instead, there are measuring scales, cardboard cut-outs, water bottles and notebooks dotted with rough calculations. The lesson is not about memorising a formula. It is about understanding why a pulley reduces effort, or how fractions behave when translated into real objects rather than symbols on a blackboard.

For many of these students, this is the first time mathematics and science feel real.

This shift from recitation to experimentation sits at the heart of a growing global consensus: children do not learn science by listening to it. They learn it by doing it.

Across education systems worldwide, STEM has become a policy priority, yet classrooms continue to rely on pedagogies that actively push students away from science and mathematics. India’s challenge is particularly stark. Despite near-universal enrolment at the elementary level, learning outcomes in maths and science in government schools remain low by the time students reach adolescence.

The problem is not curriculum overload alone. It is the way knowledge is delivered.

The global evidence for activity-based learning

Decades of research show that activity-based and inquiry-led learning leads to stronger conceptual understanding than traditional lecture-driven instruction. A landmark meta-analysis published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that students in active learning STEM classrooms were significantly less likely to fail than those taught through lectures alone (PNAS, 2014).

Importantly, this evidence is not limited to high-income countries. Studies in low- and middle-income contexts, including research published in World Development and Comparative Education Review, show that hands-on pedagogy improves comprehension and retention even in resource-constrained classrooms. What matters most is not technology or infrastructure, but pedagogy.

This becomes critical during the middle-school years. Between Classes 6 and 8, students encounter abstraction in mathematics and science for the first time. Without conceptual grounding, many disengage permanently. For girls, this disengagement is compounded by social norms, confidence gaps and the absence of visible STEM role models.

UNESCO’s Global Education Monitoring Report (2023) notes that while girls perform on par with boys in science at the primary level, participation drops sharply in adolescence, particularly in rural and low-income settings. The reasons are rarely cognitive. They are structural, social and pedagogical.

India’s learning crisis is not a curriculum crisis

India’s National Education Policy 2020 recognises these issues. It calls for experiential learning, critical thinking and reduced content load. Yet policy intent has struggled to translate into classroom practice.

Teachers in government schools are often expected to deliver ambitious reforms with limited training, overcrowded classrooms and few teaching aids. Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) data repeatedly shows that by Class 8, fewer than half of students can solve basic division or apply foundational scientific reasoning. These are not failures of ability. They are failures of instruction.

Activity-based learning directly addresses this gap. Instead of positioning the teacher as the sole authority, it invites students to test, question and collaborate. Mistakes become part of the learning process rather than a source of shame. This matters deeply in classrooms where fear of being wrong dominates participation.

Why hands-on STEM matters especially for girls

For girls, the stakes are higher. Research published in Nature Human Behaviour and Educational Research Review consistently shows that confidence, rather than competence, is the primary barrier to girls’ continued participation in STEM. Classrooms that reward speed and public correctness tend to silence students who are socialised to avoid visible error.

Activity-based learning shifts this dynamic. Group experiments and problem-solving tasks reduce the psychological distance between girls and STEM subjects. A 2022 review in Educational Research Review found that inquiry-based STEM instruction significantly improved girls’ self-efficacy and interest in science, even when test-score gains were modest.

Over time, these shifts matter. Attitudes shape aspiration, and aspiration shapes persistence.

From pilot projects to system strengthening

Against this backdrop, Smile Foundation’s introduction of a STEM Activity Handbook for Classes 6 to 8 in Siddharthnagar under its education intervention reflects a system-strengthening approach rather than a one-off intervention. Developed in collaboration with the District Education Administration, the handbook helps teachers translate abstract curriculum concepts into hands-on classroom activities using locally available materials.

The emphasis is not on replacing the syllabus, but on reinterpreting it. Each activity aligns with prescribed learning outcomes while offering structured guidance for experimentation, discussion and reflection. This is critical because one of the biggest barriers to pedagogical reform is teacher confidence. Without practical tools, calls for experiential learning remain aspirational.

The handbook also places deliberate emphasis on encouraging girls’ participation in STEM classrooms. By designing activities that reward collaboration, reasoning and curiosity rather than rote recall, it creates space for girls to engage meaningfully with mathematics and science.

Global evidence supports this approach. Research from the OECD and Brookings Institution shows that gender gaps in STEM narrow significantly in classrooms that prioritise inquiry, teamwork and problem-solving over competitive testing.

The formal launch of the handbook by the district’s Basic Education Officer matters not as ceremony, but as signal. When district administrations endorse pedagogical change, it moves activity-based learning from the margins to the mainstream.

Teachers remain central to STEM reform

Activity-based learning does not diminish the role of teachers. It reshapes it. Teachers become facilitators, guides and observers rather than mere transmitters of information.

This transition requires sustained support. Research published in Teaching and Teacher Education shows that successful adoption of inquiry-based pedagogy depends on continuous professional development, peer learning and classroom-ready resources. One-off workshops rarely change practice.

Smile Foundation’s broader education work reflects this insight by embedding teacher support into its interventions. By offering structured tools instead of abstract directives, it reduces the cognitive and logistical burden on teachers already working under pressure.

The danger of getting STEM reform wrong

There is a risk in equating STEM reform with technological fixes alone. Tablets and smartboards, while useful, cannot substitute for conceptual understanding. Without pedagogical change, technology simply digitises rote learning.

Activity-based learning offers a corrective. It reframes STEM education not as early job training, but as the cultivation of curiosity, reasoning and confidence. These capacities matter as much for democratic citizenship as for future employment.

The World Bank’s World Development Report (2018) made this clear: the skills most needed for the future of work are adaptability, problem-solving and the ability to learn continuously. Activity-based learning builds these foundations early.

The transformation of STEM education in India’s government schools will not come from headline-grabbing reforms alone. It will come from quieter shifts in classroom practice that make learning participatory rather than punitive.

The experience in Siddharthnagar offers a glimpse of what is possible when policy intent meets pedagogical realism. A handbook may appear modest in scale, but in classrooms where science has long been reduced to chalk and talk, it can change how students see themselves as learners.

For girls, these changes are especially consequential. When classrooms invite them to experiment, question and lead, futures in STEM become imaginable rather than abstract.

The evidence is clear. Activity-based learning works. The real question is whether India is willing to invest in the slow, relational work required to make it stick. In a system often driven by speed and scale, depth may be the more radical reform.