Walk into a government school in rural India. The classrooms are full, children are in their seats, teachers are at the blackboard. On paper, the numbers might look impressive: more than 96 percent of children aged 6 to 14 are enrolled in school.

But pause for a moment. Hand a Grade 5 child a Grade 2-level storybook and ask them to read. More often than not, they will stumble. Ask another to solve a simple subtraction problem. Chances are, they will look at you blankly.

This is the paradox at the heart of India’s education system. Children are in school, but many of them are not learning the basics. And those basics — what education experts call Foundational Literacy and Numeracy (FLN) — are the very skills that unlock every other stage of learning. Without them, the ladder of education becomes shaky and unreliable.

So why does FLN matter so much and why is the age of 10 such a critical milestone?

The Learning Crisis in Plain Numbers

The Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) 2023 tells us something sobering: nearly half of Grade 5 children in India still cannot read a simple Grade 2 text. In mathematics, the situation is just as troubling. Barely one in five Grade 3 students can solve a basic subtraction problem.

It’s not that children aren’t going to school — they are. But being present in a classroom does not guarantee learning.

COVID-19 only made this worse. Two years of school closures erased nearly a decade of slow progress in reading and arithmetic. By 2022, learning levels had slipped back to what they were in 2012. For children from rural and low-income households, where parents often lacked resources to support learning at home, the damage was even deeper.

In short: India’s schools are open, but for too many children, the doors to actual learning remain closed.

The Turning Point

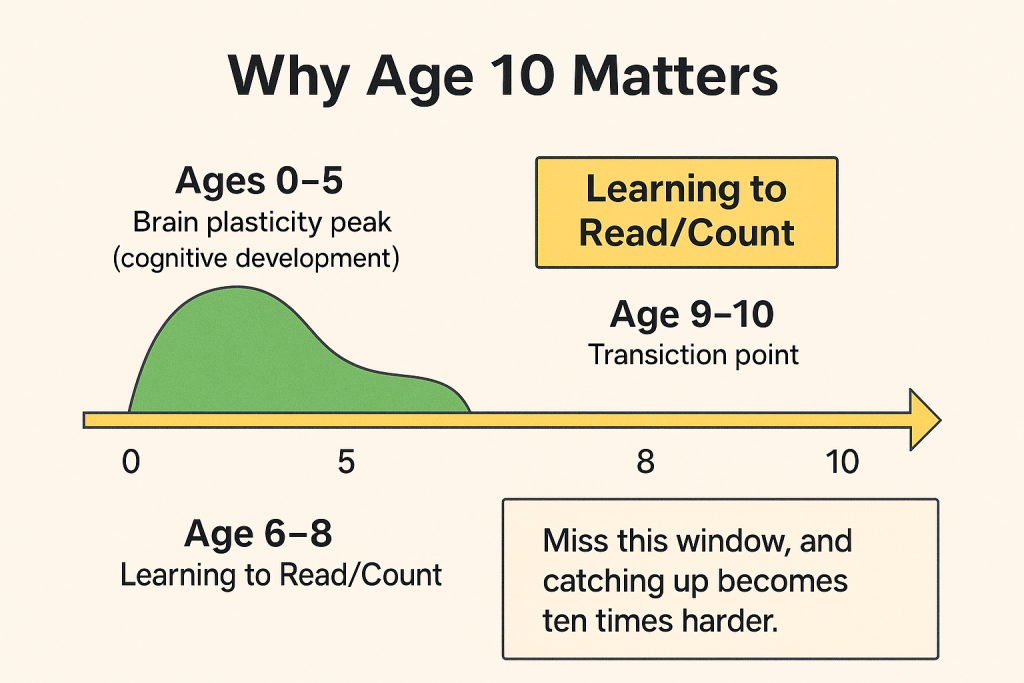

Let’s put aside the data for a moment and think about childhood. Up to around age 8 or 9, children are in the stage of “learning to read.” They are decoding letters, sounds, words and numbers. By the time they reach age 10, something important happens: they are expected to flip that switch and begin “reading to learn.”

If that switch doesn’t happen, the consequences are serious. A child who cannot read fluently by Grade 3 struggles to keep up with science, social studies or even word problems in math. Their self-confidence takes a hit and they begin to disengage.

Research by education scholar J. Douglas Willms shows that students who leave primary school without adequate reading skills are much more likely to face difficulties all the way through secondary school. The effects spill over beyond academics: poor foundational skills are linked to low self-esteem, behavioural challenges and even higher risks of anxiety and depression.

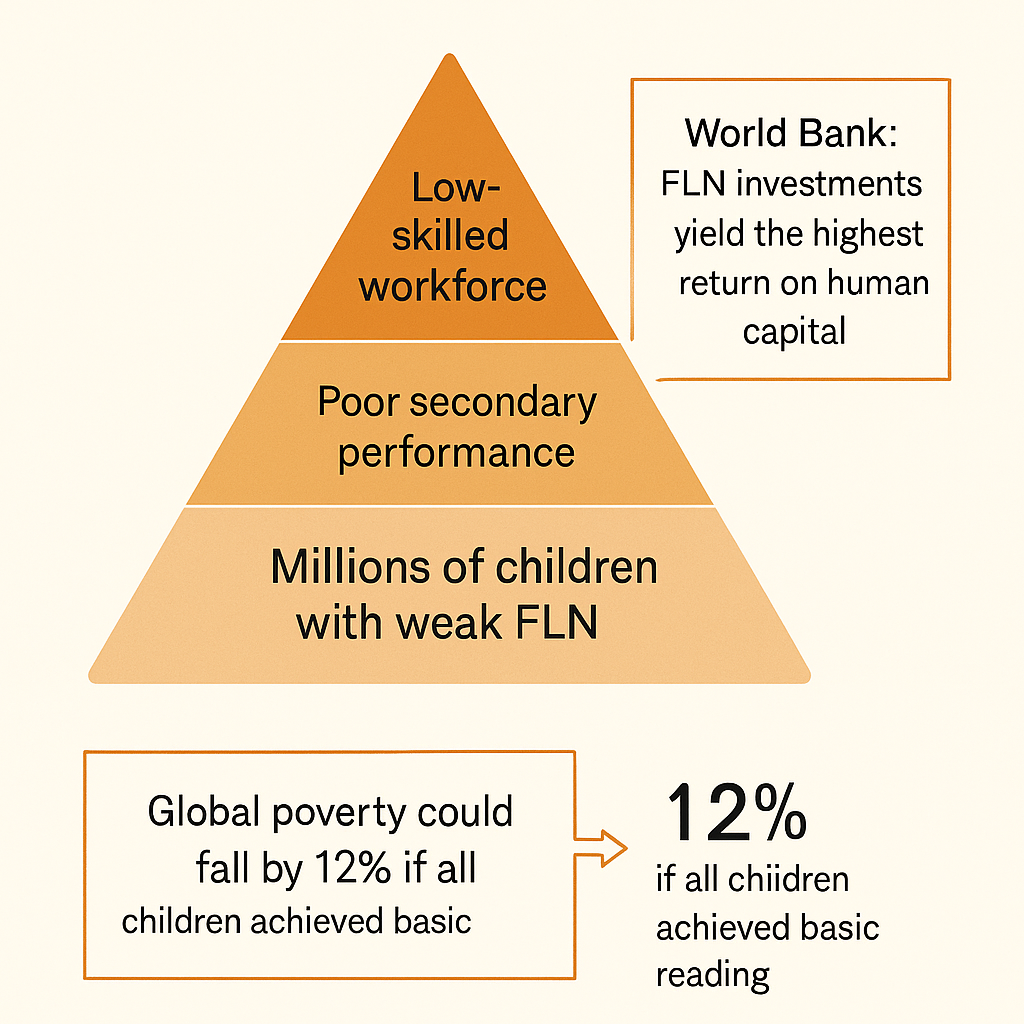

The World Bank has gone as far as to call investment in foundational learning the single highest-return investment a country can make in human capital. For India, where millions of young people will enter the workforce in the coming decade, ensuring FLN by age 10 isn’t just an educational goal — it’s an economic and social imperative.

The Indian Context: Promise and Problems

India is not blind to this challenge. The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 puts foundational literacy and numeracy right at the top of its priorities. It emphasises play-based and activity-based learning in early years, mother-tongue instruction and smaller class sizes where possible.

Building on that, the government launched the NIPUN Bharat Mission in 2021. Its goal? To ensure that every child in India can achieve FLN by the end of Grade 3, with a target year of 2026-27. The mission encourages early assessments, teacher training and close engagement with families.

On paper, this is exactly what India needs. But anyone who has spent time in a government school knows the hurdles: overcrowded classrooms, teachers who are under-trained in FLN pedagogy, children coming from homes where no one can read to them in the evenings and of course, the vast linguistic diversity that makes “one-size-fits-all” teaching almost impossible.

The truth is, schools alone cannot solve this. Families, communities and civil society all need to play a role.

What FLN Looks Like on the Ground: Stories of Change

This is where organisations like Smile Foundation step in. Through our Mission Education programme, Smile works in more than 2,000 villages across 26 states. The goal is simple yet ambitious: to make sure at least 70 percent of enrolled children achieve foundational literacy and numeracy.

But here’s the twist: Smile doesn’t teach children strictly by grade. Instead, we group them by skill level. That means a Grade 4 child struggling with reading won’t be lost in a class that has moved on to advanced material. The teaching meets the child where they are.

Language also matters. Smile Foundation prioritises instruction in the mother tongue during the early years, helping children grasp concepts faster and retain them longer. And critically, the programme doesn’t stop at the classroom. We bring in parents, school management committees and local officials, creating a supportive ecosystem around the child.

The results speak volumes. In one project under Smile’s Shiksha Na Ruke initiative in Gurugram, the percentage of Grade 3 children who could read simple sentences jumped from 38 percent at baseline to 72 percent after targeted FLN interventions. Writing skills improved from 36 percent to 93 percent.

These are stories of children who once sat silently in classrooms, now standing up and reading aloud with confidence.

Barriers We Must Confront

Even with inspiring models, India’s FLN journey faces stubborn obstacles.

- Teaching quality and training: Many teachers are not trained in age-appropriate, activity-based FLN methods. Teaching often defaults to rote memorisation.

- Language barriers: Millions of children start school in a language they don’t speak at home, making early learning unnecessarily difficult.

- Home environments: In rural and low-literacy households, parents cannot always support homework or provide books. This widens the gap between privileged and disadvantaged children.

- Assessment and remedial action: Too often, children who are struggling are not identified until much later. By then, catching up is much harder.

- Equity gaps: Girls, children with disabilities and those from tribal or minority language groups are especially at risk of being left behind.

Unless these barriers are systematically addressed, India will continue to see high enrolment rates but low actual learning.

What Can Be Done: A Roadmap for FLN by Age 10

So how do we ensure every child crosses the FLN milestone by age 10? Here are some essential steps:

- Start early and focus on the first three grades. Invest in pre-primary education so children arrive at school ready to learn. Prioritise play, storytelling and numeracy activities in the first years.

- Teach in the child’s language. Research shows children learn best in their mother tongue in early years. Building literacy in the home language provides a foundation for learning additional languages later.

- Support teachers, not just students. Train teachers in activity-based methods, give them access to high-quality teaching-learning materials and provide continuous mentoring.

- Assess early and often. Simple, classroom-friendly assessments can help identify struggling learners by the end of Grade 1, so remedial support can begin immediately.

- Engage families and communities. Equip parents with simple reading and counting activities. Run community reading sessions. Show families why FLN matters for their child’s future.

- Leverage civil society partnerships. Scale up proven models like Smile Foundation’s Mission Education, which combine classroom support with community mobilisation. Government alone cannot do it all.

- Fund FLN like the national priority it is. Budgets must reflect the urgency. Investing in early learning is not a cost — it is the most cost-effective way to secure India’s human capital future.

Why FLN Matters Beyond the Classroom

Foundational literacy and numeracy are not just about reading textbooks or solving sums. They are about agency.

A child who can read is a child who can understand a medicine label, apply for a job, or read about their rights. A child who is numerate can manage money, measure ingredients or compare prices. These are life skills as much as academic skills.

Economically, the stakes are immense. The World Bank estimates that if all children in low- and middle-income countries, including India, acquired basic reading skills, global poverty could be cut by 12 percent. In India, where millions will join the labour force each year, a failure to achieve FLN translates into lost productivity, lower wages and weaker competitiveness.

Socially, FLN is about equity. When the poorest and most marginalised children fail to learn to read or count by age 10, the gap between them and their peers only widens. Ensuring universal FLN is thus not just an education target — it is a matter of justice.

The Bottom Line

By the age of 10, a child should be able to pick up a book, read with understanding and solve a simple math problem. That is the bare minimum we owe them. Yet today, millions of Indian children are being denied even this.

The good news is that we know what works. Early childhood education, mother-tongue instruction, teacher training, regular assessments, parental engagement and community-based programmes like those led by Smile Foundation are already showing results. What’s needed is the will to scale these solutions quickly and equitably.

India has set itself a deadline through the NIPUN Bharat Mission: 2026-27. That is not far away. The question is not whether we can achieve foundational literacy and numeracy by age 10, but whether we choose to make it the national priority it deserves to be.

Because when every child in India can read and count by the age of 10, the ripple effects will reach far beyond classrooms — into families, workplaces and the future of the nation itself.