Shreya, a young girl from Himachal Pradesh’s Kangra valley, has a dream: “I want to move so far ahead in life that I don’t have to make my father do the work he currently does. I want to take care of my family.”

Hundreds of kilometers away, in Kulamua, Assam, Antora echoes a similar wish: “I dream of giving my family a comfortable life, a good life.”

These are not extraordinary dreams. They are as ordinary — and as essential — as any dream a child in Delhi, Bengaluru or Mumbai might have. But for millions of India’s tribal children, the simple act of dreaming big is itself an act of courage.

Why tribal education matters

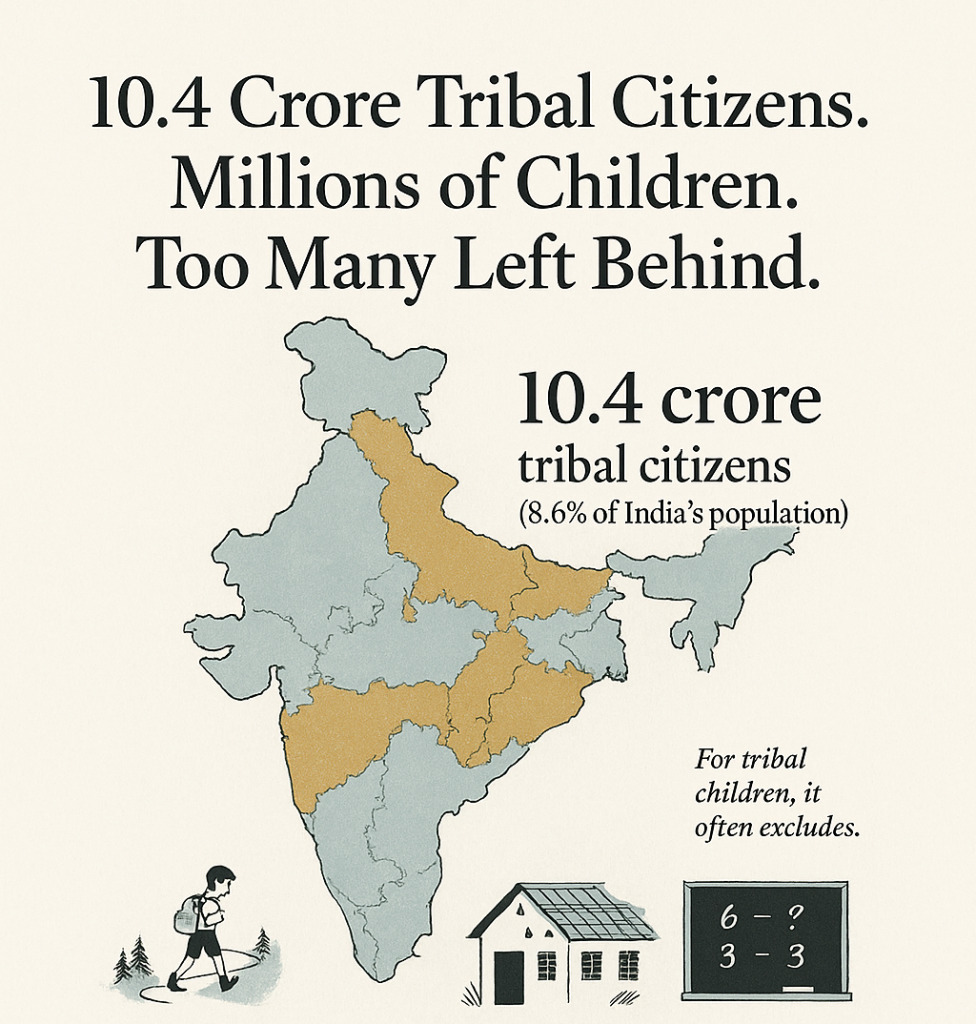

India is home to 10.4 crore people from Scheduled Tribes—8.6% of our population. They belong to hundreds of unique communities, speak dozens of languages, and live across forests, mountains, deserts and islands. Yet, their children face barriers to education that most urban families cannot even imagine.

Think about it — while one child’s worry is whether they’ll get a tablet for online classes, a tribal child’s worry might be whether the nearest school even has a roof. While one child is enrolled in coaching for IIT, another is walking five kilometres through a forest just to attend a Class 4 session.

Education, in theory, is the great equaliser. But for tribal children, it often becomes the great divider.

The ground reality

Why do so many tribal children drop out of school?

- Geographic isolation: Villages are scattered, schools are distant, roads are nonexistent. For a child in Bastar, a “school nearby” might still mean a two-hour trek through forest paths.

- Infrastructure gaps: Even when schools exist, they may not have trained teachers, safe classrooms, toilets or learning materials. A leaking roof can be enough to deter attendance.

- Economic pressure: Survival comes first. If a child can graze goats, fetch firewood or work in fields, that’s one less burden on the family. Education becomes a luxury they cannot afford.

- Cultural disconnect: Curriculums are designed in urban centres, often ignoring tribal languages, values and lived realities. Imagine being taught history that never mentions your people or science in a language you barely speak.

- Bureaucratic hurdles: Even schemes meant for tribal upliftment get tangled in red tape. Delayed disbursements, documentation demands, and lack of local planning all erode trust.

Shreya and Antora: Small stories, big lessons

At Smile Foundation’s Mission Education centres in Kangra and Kulamua, Shreya and Antora have found something rare — classrooms that feel like home.

Shreya, once hesitant, now raises her hand proudly: “Pehle mai participate nahi karti thee, ab mai participate kar rahi hoon.” (Earlier I did not participate; now I am involved in everything.)

Antora, for her part, calls her school “a gift for us.”

The national picture: A policy–reality gap

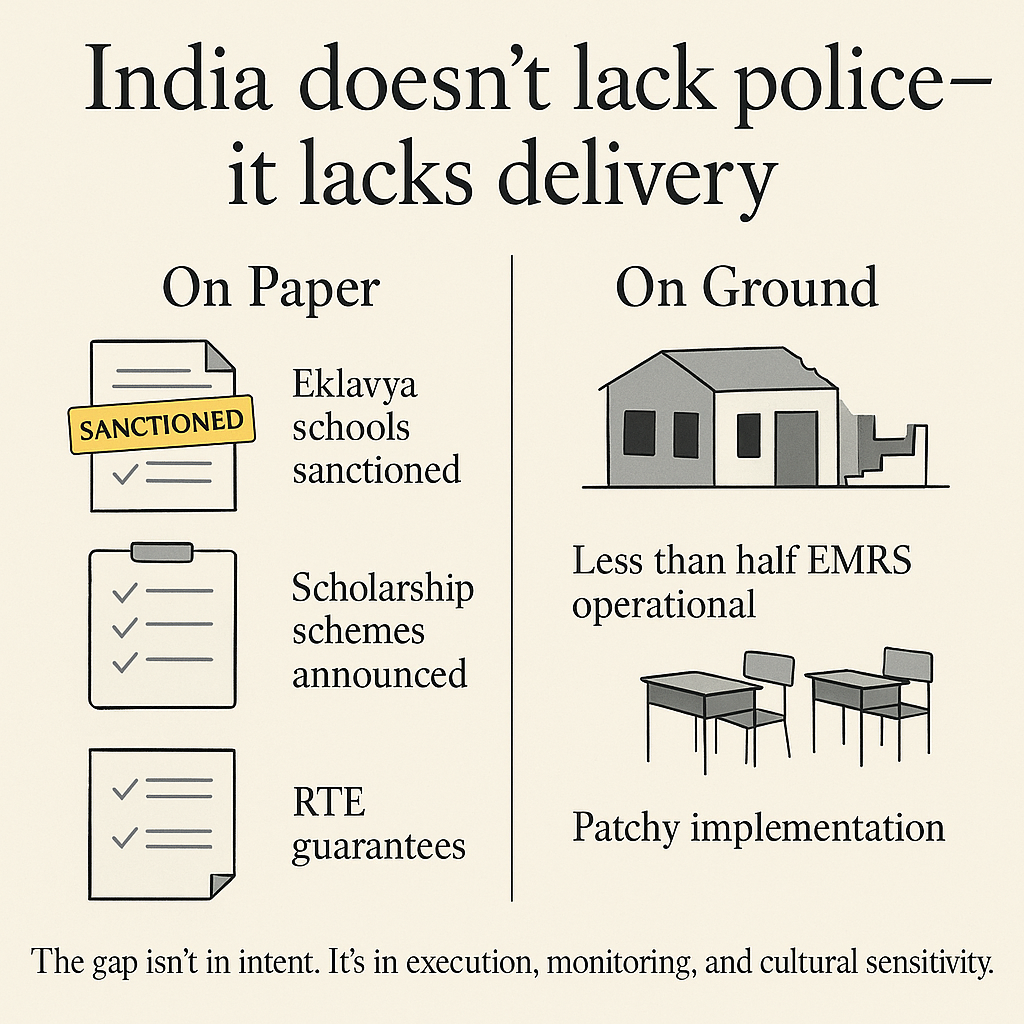

India doesn’t lack policies. From the Right to Education Act to targeted tribal scholarships, from the Eklavya Model Residential Schools (EMRS) to state-level incentives, there’s no shortage of programs on paper.

But execution is still patchy. EMRS schools, for instance, aim to set up one residential school in every block with 50% tribal population. But as of 2023, less than half of the sanctioned schools are fully functional. In many states, dropout rates among tribal children remain significantly higher than the national average.

This gap is not about intent — it’s about delivery.

What needs to change

So how do we turn policy intent into classroom reality? Here’s a roadmap worth considering:

- Localised, culturally rooted education: Curriculums must respect tribal culture, values and languages. Teaching in mother tongues in early grades can dramatically improve learning outcomes.

- Vocational pathways: Culturally relevant vocational programmes — be it eco-tourism, sustainable agriculture or forest management — should be woven into secondary education. This makes school meaningful for families too.

- Flexible access models: Mobile schools for nomadic tribes, year-round admissions and reduced documentation can widen the entry gate.

- Empowered local monitoring: Panchayats, community leaders and local NGOs should be equipped to oversee schemes, track teacher attendance and plug gaps.

- Holistic support: Free coaching, counselling and mentoring can help tribal children not just stay in school but aim higher — entrance exams, skill-building and career planning.

- Higher education access: Setting up IGNOU-style distance education institutes in tribal belts can make college affordable and reachable.

- Corporate and NGO partnerships: Companies under CSR and NGOs like Smile Foundation can complement state efforts, experimenting with models that government schools can later adopt.

Why it’s worth it

- Economic dividend: Tribal communities make up a large share of India’s population. Investing in their education unlocks a vast pool of human capital.

- Social equity: Education is the fastest way to reduce long-standing inequalities rooted in caste and tribe.

- Cultural preservation: Education that respects tribal heritage ensures languages, art and traditions are not lost.

- National integration: A child who feels included in the education system is more likely to feel included in the nation’s story.

Every pencil, a new future

There’s a striking image often shared in classrooms of a pencil as a weapon of change. Every time a tribal child picks up a pencil, they challenge centuries of exclusion. They signal to the world: I belong here, I matter, and I will write my own story.

And when children like Shreya and Antora succeed, the ripple effects are enormous. An educated daughter inspires younger siblings. An employed son supports aging parents. A literate household pushes for better governance. One pencil can rewrite an entire community’s future.

Educating tribal children is about giving children born in forests, deserts and mountains the same right to dream as those born in cities.

NGOs like Smile Foundation are showing what’s possible with community-driven, culturally sensitive models. But to scale this, India needs a coalition: governments, corporations, NGOs and citizens working together.

If India is serious about becoming a knowledge economy, about harnessing its demographic dividend, then no child — especially those furthest from the spotlight — can be left behind.

Closing thought

Shreya’s dream is to ease her father’s burden. Antora’s dream is to give her family a comfortable life.

Neither dream should be extraordinary. And yet, in today’s India, they are.

The true measure of our progress as a nation will not be how many AI engineers we export to Silicon Valley, but how many tribal children we empower to dream freely and how many of those dreams we help come true.

Because in the end, a nation is only as strong as the dreams it nurtures.