Economists like to ask what replaces what. When a new technology enters everyday life, what does it substitute, and at what cost? In India, the smartphone has substituted classrooms during pandemics, libraries in crowded homes, and long journeys to government offices. It has replaced waiting with immediacy and distance with access. What it has not replaced—at least not yet—are the social protections that usually accompany entry into public life.

For adolescent girls, this gap has proved consequential.

India now has more than 750 million smartphone users. The growth has been swift and uneven, propelled less by leisure than by necessity. During the pandemic, phones became classrooms. After it, they remained lifelines—to teachers, friends, government portals, potential employers. Digital access, once a marker of privilege, hardened into expectation. Digital safety, by contrast, lagged behind, treated as a private matter to be negotiated within families.

The result is a familiar pattern in development history: the benefits of progress arrive upfront, while the costs surface later, distributed quietly and unevenly. Girls, as they often do, absorb those costs first.

An incomplete market

From an economist’s perspective, this is an incomplete market. Access expanded without safeguards; participation increased without protection. Girls were invited into a vast public space—the internet—without the social infrastructure that usually regulates public life: norms, accountability, recourse.

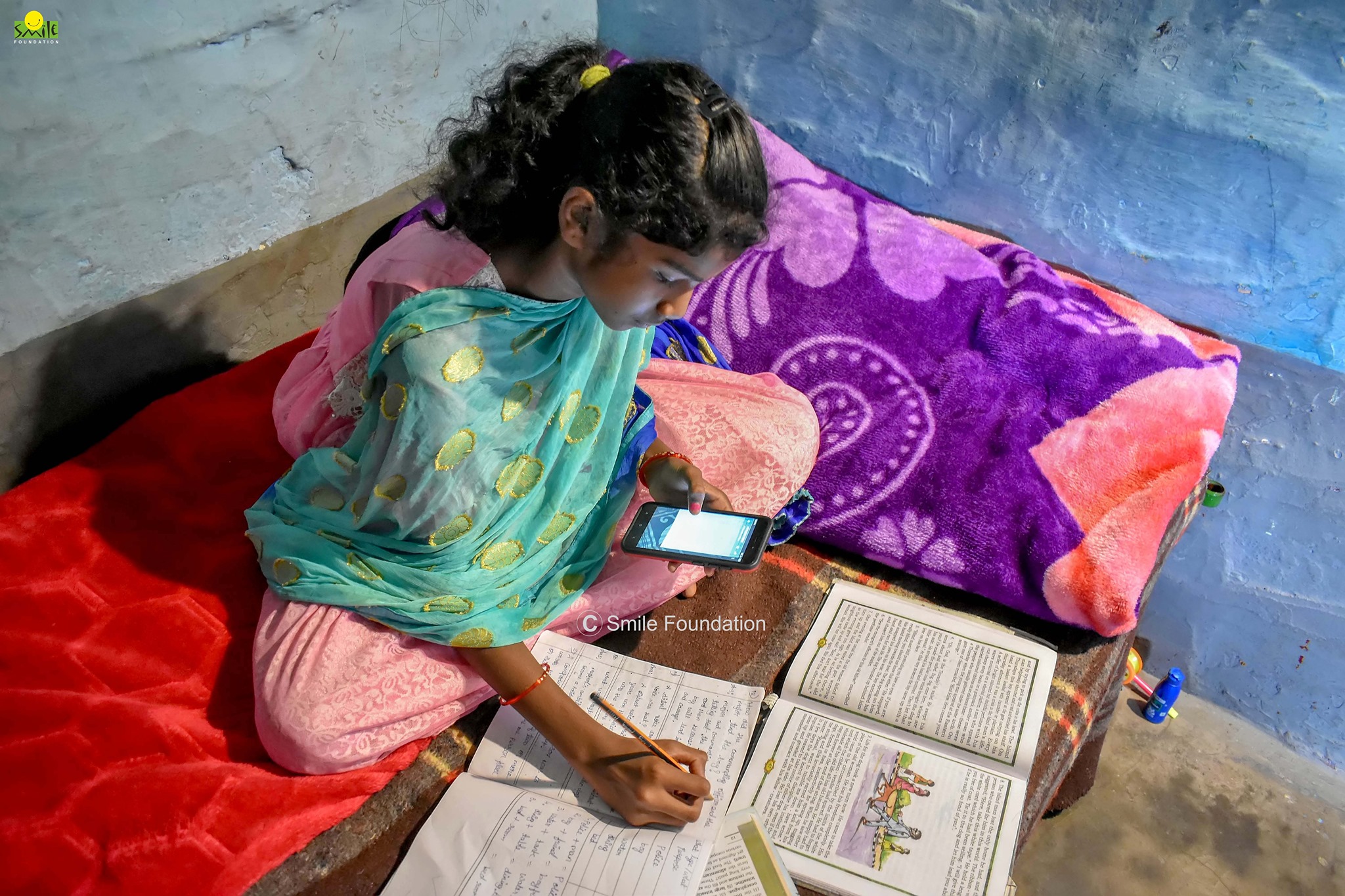

Consider how this plays out. A smartphone lands in a household during COVID-19, bought for online classes. The device is shared. Passwords are known. Privacy is conditional. A girl learns to navigate WhatsApp groups and YouTube tutorials with speed and ingenuity, often teaching adults around her. She also learns, without instruction, to manage attention from strangers, rumours among peers, and the lingering fear that a screenshot can travel faster than truth.

National surveys capture the expansion of access but struggle to register its texture. According to IAMAI–Kantar’s Internet in India 2023 report, adolescents are among the fastest-growing cohorts online, with a narrowing gender gap in access. What the data doesn’t show is how access feels when it is policed, shared, and surveilled—when the promise of connection arrives bundled with risk.

When safety becomes surveillance

In many households, concern about online harm translates into control rather than conversation. Phones are confiscated at night. Passwords are demanded. Girls are warned to “be careful” without being told what caution looks like. If something goes wrong—an unsolicited message, a doctored image—the response is often punitive. Why were you online? Why did you reply?

This is not parental cruelty so much as institutional absence. Schools rarely teach digital citizenship in ways that grapple with consent, boundaries, and reporting. Teachers themselves are uncertain, wary of discussing sexualised harassment in online spaces. The National Education Policy gestures toward digital literacy, but implementation remains uneven and narrow, focused on functional skills rather than social ones.

In the vacuum, responsibility is individualised. Safety becomes a test of character. Girls learn to self-censor, to disappear from platforms, to carry risk quietly. The phone does not close at night; the anxiety does not either.

The economics of attention

The smartphone is not a neutral tool. It is an attention economy designed to reward visibility and engagement. For adolescents—especially girls—this creates pressures that are hard to name and harder to resist. Social comparison is constant. Algorithms surface ideals of beauty, success, and romance that are both aspirational and punishing.

Clinicians in urban India report a rise in anxiety and sleep disruption among adolescent girls, patterns mirrored in global research linking heavy social media use to mental distress. India’s mental health data remains sparse, but the stories accumulate: girls who withdraw from class discussions, who scroll late into the night, who feel watched even when alone.

What makes these harms elusive is their invisibility. A girl scrolling appears occupied, not overwhelmed. Distress is mistaken for distraction.

Gendered risk

Boys and girls experience the internet differently. Boys are more likely to be encouraged to explore, to fail and recover. Girls are taught to anticipate harm and avoid it. The asymmetry mirrors the offline world, where public spaces are navigated with caution. Online, the consequences can be swift and amplified.

Cyberstalking, non-consensual image sharing, grooming—these are not rare. The National Commission for Protection of Child Rights has repeatedly warned about gaps in reporting mechanisms for minors. Yet reporting remains low. Shame travels faster than help.

Here, an economist’s concept is useful: capabilities. Access alone does not equal freedom. What matters is whether individuals have the real ability to use resources to pursue lives they value. A smartphone without the capability to navigate it safely is not empowerment; it is exposure.

Education systems catch up—slowly

Schools could be the obvious place to build those capabilities. They are not. Digital literacy curricula, where they exist, emphasise tools, not terrain. How to submit an assignment. How to search. Rarely: how to recognise manipulation, how to set boundaries, how to seek redress.

Teachers cite discomfort and lack of training. Parents, many of whom came online late themselves, feel outpaced. Platforms promise safety features that are poorly understood and inconsistently enforced. The architecture of protection is fragmented.

And so girls learn informally, through peers and trial and error. Mistakes are inevitable. Support is not.

The first generation to grow up online

What distinguishes this moment is scale. Today’s adolescent girls are the first generation to grow up with digital footprints that begin in childhood. Their reputations—social and academic—are shaped online early. The internet does not forget easily, and forgiveness is not automated.

India’s digital public infrastructure is expanding rapidly, from education portals to health records. The state understands scale. It has not yet matched it with care.

Where civil society steps in

In the absence of robust institutional support, civil society has begun to do the slow work of translation. Digital safety, in practice, is less about rules than relationships—about spaces where girls can speak without fear of punishment and learn without spectacle.

Smile Foundation’s work with adolescent girls offers a window into what this looks like. Through programmes such as Swabhiman and Mission Education, digital safety is folded into life-skills education rather than isolated as a warning. Conversations begin with lived experience: what it feels like when a message crosses a line; how rumours move; what consent means online and offline.

Parents are brought into the room—not to police, but to listen. Counsellors link online harm to mental health, recognising that anxiety, withdrawal, and academic decline often share a digital root. The goal is not to eliminate risk—an impossible task—but to distribute responsibility.

These efforts are small compared to the scale of the problem. They matter because they treat girls as citizens-in-training rather than liabilities to be managed.

The cost of getting this wrong

The stakes extend beyond individual safety. Digital participation shapes who speaks, who leads, who is visible. If girls learn that public space—online included—is unsafe unless they shrink themselves, the costs are civic.

Economists warn that when risks are borne privately but benefits accrue publicly, markets fail. The smartphone era has delivered collective gains—connectivity, efficiency, growth—while offloading safety onto those least equipped to negotiate it. Girls pay with time, attention, and silence.

Toward a public understanding of safety

What would it mean to treat digital safety as a public good? It would mean teaching consent and boundaries alongside coding and training teachers to recognise online harm as a learning barrier. It would mean designing platforms with accountability that does not require victims to become investigators and, above all, shifting the moral frame—from “be careful” to “be prepared, and be supported.”

The girl with the cracked phone in Delhi is not naïve. She is navigating a world built quickly and explained poorly. Her safety depends less on her restraint than on our willingness to build the social infrastructure that should have accompanied access.

Progress, economists remind us, is not just about substitution. It is about who bears the costs. In India’s smartphone era, girls have carried those costs quietly. Making them visible is the first step toward sharing them.

Selected sources

- UNICEF on children and digital safety: https://www.unicef.org/end-violence/how-to-stop-cyberbullying

- IAMAI–Kantar, Internet in India 2023: https://www.iamai.in

- NCPCR guidelines on online child safety: https://ncpcr.gov.in

- Centre for Internet and Society (India): https://cis-india.org

- National Education Policy 2020: https://www.education.gov.in