Imagine a world where getting healthcare is as easy as making a phone call, where no one is forced to choose between their health and their livelihood. In this world, everyone – from bustling cities to remote villages – can access the full range of health services they need, when and where they need them, without falling into financial hardship. Health experts have a fancy term for this ideal: Universal Health Coverage (UHC). It’s a cornerstone of the Sustainable Development Goals and countries around the globe have pledged to achieve it. Turning that lofty vision into reality is no small feat, especially in the sprawling and diverse Indo-Pacific region. Yet, in the past decade, India has made giant leaps in using digital technology to bring healthcare closer to people’s doorsteps – leaps that offer fun, instructive lessons for many Indo-Pacific nations facing similar challenges.

A Tough Prescription: Health Challenges in the Indo-Pacific

From the highlands of Papua to the atolls of the Pacific, the Indo-Pacific region faces some daunting healthcare hurdles. Consider a place like the Arfak Mountains in West Papua, Indonesia: the scenery is stunning but breathtakingly unforgiving – jagged mountains, dense forests and long winding roads make it a nightmare for health workers to reach far-flung villages. In these communities, modern medicine competes with deep-rooted beliefs in witchcraft. Many villagers attribute illness to “suanggi” (sorcery) and may delay or avoid seeking treatment from clinics. Add to this a shortage of trained medical staff and scant awareness about diseases like malaria and you get a perfect storm of obstacles to delivering care.

Hop over to the Pacific Islands – say Fiji, Vanuatu or Micronesia – and you’ll find a different set of challenges with a similar result. These small island nations struggle with chronic shortages of doctors and nurses, making it hard to achieve universal health coverage. It’s not that people don’t want to train as health professionals; the issue is that there aren’t enough training opportunities locally and many of those who do qualify often move abroad for better pay and facilities.

The World Health Organization notes that nearly every Pacific Island country falls below its recommended health worker-to-population ratios. Despite various international aid programmes and WHO-supported initiatives, the remoteness and isolation of these islands, limited resources and weak health data systems have hampered sustained progress in building an equitable health workforce. In short, small populations spread across vast ocean distances face big hurdles in getting quality healthcare.

If all this sounds like a tough prescription to fill, it is. But this is where India’s recent experience can offer a dose of inspiration. India’s sheer size and diversity mean it has grappled with many of the same issues – remote communities, cultural barriers, limited doctors in rural areas – and it has found innovative, community-driven fixes. Let’s take a closer look at how India’s digital health revolution unfolded and what lessons it holds for its Indo-Pacific neighbours.

From Health IDs to Telemedicine: India’s Digital Health Revolution

Not long ago, India’s healthcare system was largely analouge and urban-centric. Medical records were paper files gathering dust and rural patients often travelled long distances to see a specialist or simply went without care. Over the last decade, however, India set out on an ambitious digital journey with a simple idea: connect every citizen to the health system through technology. The result is a rapidly evolving digital health infrastructure that is bridging the urban-rural divide and making healthcare more accessible than ever before.

At the heart of this transformation is the Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission (ABDM), launched in 2021. Think of ABDM as the digital backbone of India’s healthcare. One of its first initiatives was giving every citizen a unique digital Health ID (now called Ayushman Bharat Health Account or ABHA) to store their medical records securely in the cloud. The response has been staggering – as of early 2025, more than 73 crore (730 million) Indians have created their digital health IDs. To put that in perspective, that’s like the entire population of Europe having an interoperable digital health record! Over 5 lakh (500,000) healthcare professionals are registered on the national platform, which means a vast network of doctors and nurses can both contribute to and access patients’ records with the patients’ consent. This nationwide framework makes it possible for a person in a remote village to consult a doctor in a big city and have the prescription or test results added to their digital record instantly. It’s a game-changer for continuity of care.

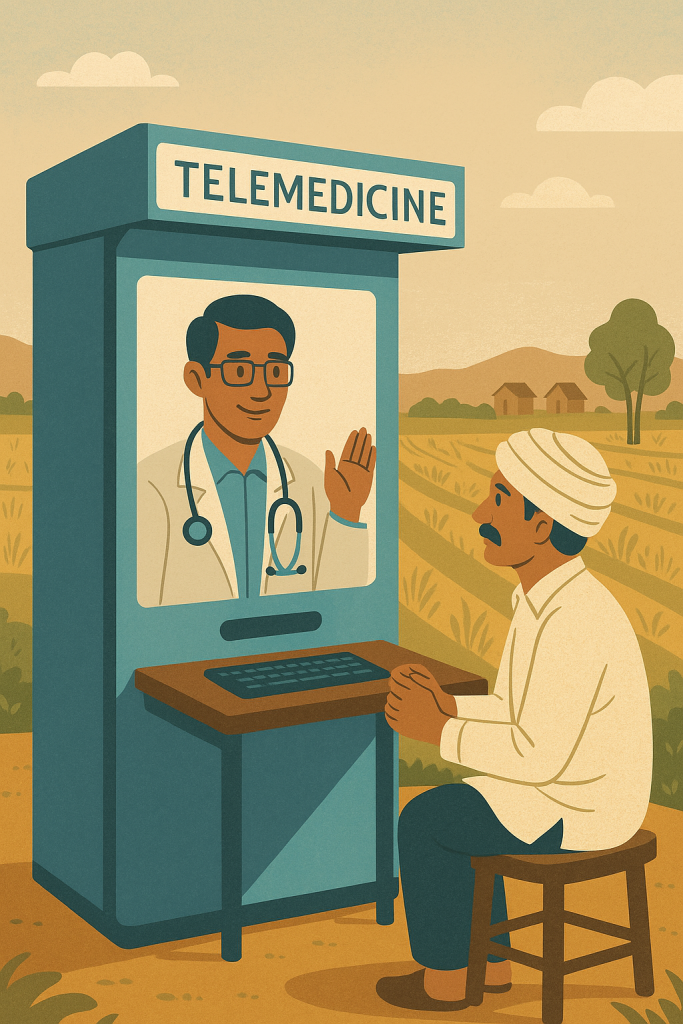

Building on this digital backbone, India has rolled out telemedicine on an unprecedented scale. The flagship telemedicine platform eSanjeevani is a prime example. Initially piloted to connect rural clinics with city hospitals, eSanjeevani became a household name during the COVID-19 pandemic when lockdowns made physical consultations difficult. Today, it’s the world’s largest telemedicine service for primary healthcare. By February 2025, eSanjeevani had facilitated over 34 crore teleconsultations (340 million and counting) since its 2019 launch. From Kashmir to Kanyakumari (north to south) and Kutch to Kohima (west to east), the platform covers all 36 states and union territories, bringing online doctor consultations to even the most sparsely served areas.

Importantly, these eSanjeevani consultations are recorded (with patient permission) into the person’s digital health account, creating a secure health history that travels with them. This integrated approach has not only eased the burden on crowded city hospitals but also ensured that people in rural and remote areas get medical advice without spending half a month’s wages on travel. Little wonder India’s Health Minister calls eSanjeevani a “health sector revolution”, noting how it has made quality healthcare available at home and “democratized healthcare”.

Telemedicine in India isn’t just about general doctor consultations either. It’s being used for specialist services and screenings. For instance, through hub-and-spoke telehealth models, a community clinic (Ayushman Bharat Health and Wellness Centre) can connect patients to a specialist in a city hospital. There are documented cases of AI-powered diagnostic tools being piloted, such as apps that help detect diabetic eye disease or cervical cancer from images, allowing local health workers to conduct screenings that would normally require a specialist. These tech tools mean that a village nurse, armed with a tablet or smartphone, can prevent serious diseases by catching them early and then consult a remote specialist via eSanjeevani for follow-up. The result is better availability of care when and where people need it, minimising the need for patients to undertake costly, arduous journeys to far-off hospitals.

India’s digital health leap is not limited to cyberspace; it also has wheels and even rudders! A number of mobile medical units – essentially clinics on wheels – are bringing healthcare to the hinterlands. The Smile on Wheels program by an NGO is one notable example: these are buses or vans outfitted as tiny clinics that visit villages on a regular schedule. In riverine areas of Assam and other states, “Smile on Boat” clinics literally sail to the remote river islands with doctors and medicines on board.

In a recent public-private initiative in Assam, two mobile medical vans and a boat clinic were launched to serve over 25,000 people annually across 12 hard-to-reach districts and river islands. Each unit comes with doctors, nurses, diagnostic equipment, and free essential medicines. Importantly, they focus on the three A’s – Availability, Accessibility, Affordability – by delivering care right to communities that previously had little access. Patients who might have been an entire day’s travel away from the nearest hospital can now get check-ups, basic lab tests and medicines in their village or island. And if a serious case is identified, the mobile clinics coordinate referrals to bigger hospitals, even assisting with transport if needed. These innovative outreach efforts show a clever blend of old-school community health (bringing services to the doorstep) with new-school tech, as some mobile units are equipped with teleconsultation facilities linking to specialists in real time. It’s healthcare on the move, quite literally.

Making Healthcare Affordable and Inclusive

One of the biggest barriers to healthcare, especially in developing regions, is cost. It’s not just the doctor’s fee; it’s the bus fare to the clinic, the day’s wages lost in travel and waiting and the price of medicines that can all add up to devastating out-of-pocket expenses. In India, these factors historically pushed millions into poverty each year. The government recognised that achieving UHC isn’t just about having services available – people need to afford and access them without hardship. Here again, digital and community innovations have helped bend the cost curve and make healthcare more inclusive.

Telemedicine = savings. Every eSanjeevani consultation a rural family does from their village saves them the cost of a trip to the nearest town or city. Multiply that by 34 crore teleconsultations and you have hundreds of millions of travel miles and rupees saved. In fact, the eSanjeevani service is provided free of charge to patients, effectively eliminating consultation fees for those who use government doctors online. According to official reports, this platform has been instrumental in “ensuring availability, accessibility and affordability” of care by providing free advice and reducing the need for physical visits. It especially benefits those who live in far-flung areas or cannot easily travel – such as the elderly, women with young children or people with disabilities.

The inclusivity impact of these digital services is striking. Over 57% of eSanjeevani’s users are women and about 12% are senior citizens. Traditionally, these groups faced greater barriers in traveling to clinics – women often have household responsibilities or societal constraints and seniors may be too frail. By bringing consultations into the home via a simple smartphone app or a common service centre, telemedicine has opened the doors of healthcare to those who were left standing outside. It’s a powerful reminder that technology, when used thoughtfully, can level the playing field. One might even say telemedicine has become the “great equalizer” for healthcare access in India, much like how mobile phones revolutionized access to communication.

Another major expense in healthcare is medicines. Here too, India has used digital platforms and clever supply-chain thinking to help citizens save money. The government’s Jan Aushadhi scheme, a network of generic medicine pharmacies, uses an online inventory system to stock affordable generic drugs at thousands of stores nationwide. These Jan Aushadhi Kendras offer quality-assured medicines at prices 50% to 90% cheaper than their branded equivalents. For example, a blood pressure pill that might cost ₹100 under a big brand name could be ₹10 at a Jan Aushadhi store. By 2024, over 13,000 such outlets were operational, often linked with digital dashboards to manage stock and demand. Patients can even use a simple online lookup to find the nearest Jan Aushadhi outlet or check if a specific medicine is available. The impact is huge: people with chronic illnesses (who need monthly meds for diabetes, heart disease, etc.) can save thousands of rupees each year.

On the private sector side, a host of online pharmacies and health apps have also emerged, competing to deliver medicines at discounts and sometimes even for free for the poorest. During the pandemic, India’s medicine delivery apps became lifelines and today many of them offer teleconsultation plus medication delivery bundles. Some startups coordinate with local health workers to ensure even remote orders are delivered via postal service or courier to villages.

Then there’s CoWIN, the digital platform India developed for its COVID-19 vaccination drive, which showcased inclusivity by design. The app and website were developed in multiple Indian languages, but recognising that not everyone has a smartphone, the system also relied on old-fashioned SMS and IVR (interactive voice response). People could register for vaccines using basic mobile phones – they’d receive OTPs and confirmation via text – and even get guidance SMS messages in 12 different languages on what to do and where to go for their shot. This multi-channel approach (smartphone app, website, call center and SMS) meant that language or lack of internet wasn’t a barrier. In fact, many village communities mobilized WhatsApp groups where one person with a smartphone would coordinate vaccine appointments for others, using CoWIN and sharing the SMS details. The CoWIN platform ended up facilitating over 2.2 billion vaccine doses, a success unimaginable without its inclusive, digital-yet-accessible architecture.

Crucially, India’s push for digital health hasn’t side lined the human touch – it has augmented it. The real heroes of India’s rural health system are the Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) – nearly one million female community health workers who are the first point of contact for care in villages. Recognising their importance, many digital initiatives are built around empowering ASHAs with new tools. For example, ASHAs across several states use a mobile app that replaces the old pen-and-paper registers for tracking pregnancies, immunisations and clinic visits.

One such app, used in Rajasthan, immediately flags high-risk pregnancies (say, if a woman’s haemoglobin is dangerously low) so the ASHA can prioritise follow-up. ASHAs also form WhatsApp groups of new mothers to share infant care tips and vaccination reminders, creating a supportive digital community. These community innovations – local language chatbots, WhatsApp help groups, voice reminders via phone calls for illiterate patients – may seem small-scale, but they significantly boost participation in healthcare programmes. During recent vaccination drives (for COVID-19 and for childhood immunisations), these personalised, community-based digital nudges helped dispel fears and improve coverage. It’s like having a friendly neighborhood health auntie in your phone, guiding and comforting you in the dialect you understand best.

Community Innovations: Health Tech with a Human Face

If there’s one theme that stands out in India’s digital health journey, it’s that technology works best when it’s woven into the community fabric. High-tech command centres and glossy apps alone won’t move the needle on public health; it’s the marriage of tech solutions with on-the-ground human effort that produces magic. India provides plenty of examples of this principle in action.

Take telemedicine again – the eSanjeevani platform is digital, yes, but its massive reach was achieved by linking it with physical Health and Wellness Centres and training community health officers to assist patients in using it. In many rural clinics, an ASHA or nurse is present to help an elderly farmer have a video call with a doctor in the city. These “telemedicine kiosks” or booths at clinics ensure that even those uncomfortable with smartphones can benefit. The technology is humanised – it comes with a helping hand.

Mobile Medical Units (the “clinics on wheels”) similarly rely on local community health volunteers to spread the word of their arrival and encourage villagers to come out for check-ups. In some remote areas, they’ve even experimented with bike ambulances and boat ambulances, and used walkie-talkies or simple apps for scheduling visits when cell networks are unreliable. It’s all about adapting to local context. In mountainous Ladakh, for instance, solar-powered telemedicine kits were given to health workers to use in villages that are cut off by snow in winter – ensuring consultations can continue even when roads are closed.

Another grassroot innovation is the use of vernacular-language voice bots and helplines. One healthcare start-up, BigOHealth, realised that many rural users struggled with text-based apps but were quite comfortable speaking over the phone. So they launched a 24/7 helpline where patients can describe their symptoms in their own language to an operator or AI-driven system, which then connects them to a doctor. By using local dialects and even illiterate-friendly interfaces (like voice commands or icon-based navigation in apps), such services break the literacy barrier. This approach has been vital in expanding the reach of digital health in a country with dozens of languages and varying education levels.

Perhaps the most powerful lesson from India’s experience is that trust and technology must go hand in hand. People trust people – the local nurse, the ASHA didi (sister), the friendly pharmacist – more than a distant app or website. So India has often put those trusted people at the center of its digital rollouts. The government didn’t just launch a Health ID and wait for people to sign up; it enlisted ASHAs and village councils to help families register for their digital IDs during health camps. It wasn’t just a top-down tech deployment, but a ground-up mobilisation. This community-first mindset ensured that digital health tools were seen not as alien intrusions, but as helping hands that amplified what communities were already doing.

Lessons for the Indo-Pacific: A Healthy Dose of Innovation

So, what can countries across the Indo-Pacific region take away from India’s digital health leap? While every nation has its unique circumstances, a few broad lessons emerge that could be as useful as a first-aid kit:

- Meet people where they are (literally and linguistically): A one-size-fits-all approach won’t work for diverse communities. Health tech must be tailored to local languages, cultural beliefs and realities on the ground. That might mean having vaccine registration platforms that operate in multiple languages and even via basic SMS – like India’s CoWIN did or using audio and video content to reach populations with low literacy. Humanising the technology is key: a chatbot that speaks the local dialect or informational videos featuring community leaders can go a long way in building trust.

- Empower the frontline troops: Community health workers are the unsung heroes in healthcare delivery. Training and equipping them with digital tools can multiply their impact. Imagine a village midwife in the Pacific islands using a tablet app to monitor pregnancies or a health volunteer in a Papuan village doing a video call with a distant doctor to treat a fever. When frontline workers become fluent in using these technologies, they serve as both care providers and tech educators for the community. Plus, their endorsement can assuage fears of new technology. Investing in their continuous training (and yes, paying them decent wages) is one of the best moves a health system can make.

- Bring the clinic to the community: Distance and difficult terrain are common challenges in the Indo-Pacific. If people can’t easily reach healthcare, bring healthcare to them. Mobile clinics on vans, boats or even motorbikes can deliver basic services and preventive care. Set up telemedicine kiosks in post offices or community centres where people can drop in for an online consult. Use radio or SMS blasts to send health alerts (for example, reminders for vaccination drives or malaria precautions before the rainy season). These last-mile delivery innovations, as India showed, can dramatically expand access while keeping costs low. In Assam’s case, a couple of boat clinics now serve dozens of islands that had no doctor visits before – an idea easily replicable in archipelagos or riverine communities elsewhere.

- Public-private partnership is a prescription for success: One striking aspect of India’s digital health story is the ecosystem that formed. The government built foundational infrastructure (like ABDM, eSanjeevani, CoWIN), but a lot of the innovation came from start-ups, NGOs and the private sector plugging the gaps – be it low-cost apps, health devices or last-mile delivery methods. This kind of collaboration can greatly benefit Indo-Pacific countries. Governments can provide support and scale, while NGOs and tech innovators provide agility and fresh ideas. For example, an NGO in the Solomon Islands might pilot a solar-powered telehealth kit for outer islands, which the government can then scale up nation-wide if successful. Or a tech company in Fiji might develop a bilingual health app for diabetes management that could be adopted by the public health department. Breaking silos and working together multiplies impact.

- Commitment and continuity matter: Digital leaps don’t happen overnight. India’s progress came from years of policy push (like the National Digital Health Blueprint) and sustained funding in both tech and basic healthcare. Indo-Pacific countries looking to emulate this should view it as a journey – start with pilot projects, learn and adapt, and importantly, scale up what works with political and financial commitment. Even maintaining a simple telemedicine network requires training people, updating software and spreading awareness so that citizens know such services exist. Consistency in approach, with room to tweak based on feedback, will build public confidence over time.

In essence, the Indo-Pacific region can take a page from India’s playbook: leverage technology to leapfrog traditional barriers, but do it in a way that’s grounded in community needs and human relationships. A digital health tool is only as good as its adoption by the people on the ground. And people embrace what they find useful, affordable and trustworthy.

A Healthier, Shared Future

India’s digital health leap isn’t about shiny gadgets or cutting-edge AI in isolation – it’s about how these tools were used to include and uplift communities. It demonstrated that a developing country can indeed pioneer health innovations and implement them at mind-boggling scale. For nations across the Indo-Pacific, from small islands to vast archipelagos, the core message is optimistic. You don’t have to wait decades to build hundreds of hospitals and train thousands of doctors to start improving healthcare access. By intelligently deploying technology – and partnering with the people who know their communities best – even resource-constrained countries can make rapid, meaningful gains.

The path to Universal Health Coverage will look a bit different in each country, but sharing successes and solutions is vital. India’s experience shows that digital health, when done right, can be a great leveler, making healthcare more democratic and patient-centric. Other countries in the region are already taking note and adapting these ideas to their contexts. In Bangladesh and Indonesia, for example, telemedicine and health hotlines have taken off. In the Pacific, countries are exploring digital health record systems and e-learning for health workers with support from international partners.

As we move forward, imagine an Indo-Pacific where a mother in a remote Pacific isle can consult a pediatrician in the capital via telehealth, where a community nurse in Papua has a solar backpack to power her medical tablet, where medicine deliveries by drone or boat are routine, and where health awareness info is as common on local radio as the weather report. It’s not a far-fetched dream – it’s the next logical step, building on innovations already in motion.

The famous saying “health is wealth” holds true not just for individuals but for nations. By learning from each other and scaling up community-based digital innovations, we can make huge strides toward that world of accessible, affordable, quality healthcare for all. In doing so, they won’t just be improving health outcomes – they’ll be investing in the overall well-being and economic future of their people. And that is a dividend that will pay off for generations to come. The doctor is (virtually) in – now it’s time to make sure everyone can get an appointment.

Sources:

- UNICEF – Challenges of healthcare delivery in remote West Papua

- CSIS – Pacific Islands health workforce shortages and migration issues

- Press Information Bureau (Govt. of India) – Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission stats (73+ crore health IDs, 5+ lakh providers)

- The Economic Times – India’s eSanjeevani telemedicine platform crosses 34 crore consultations (impact on accessibility and affordability)

- Invest India – Telehealth usage in India (57% women and 12% senior beneficiaries)

- ET Healthworld – Jan Aushadhi scheme providing medicines 50–90% cheaper than market prices

- Syllad News – Mobile medical units (“Smile on Wheels/Boat”) serving remote areas in Assam and focusing on availability, accessibility, affordability