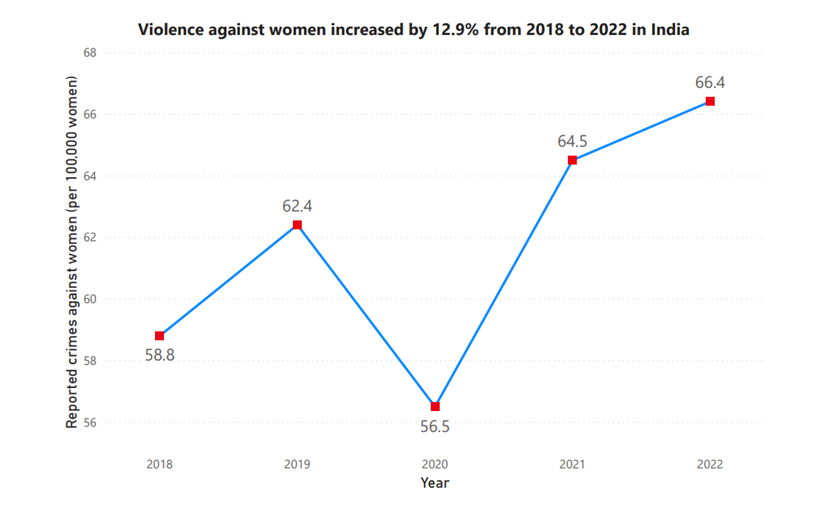

Crimes against women – ranging from domestic abuse to sexual assault – are a pervasive global issue. The World Health Organization estimates that at least one in three women worldwide has experienced physical or sexual violence in her lifetime. In India, entrenched patriarchal norms and economic dependency often compound the problem. Official data show disturbing trends: the 2022 NCRB report recorded 66.4 crimes per 100,000 women, up from 58.8 in 2018 (a 12.9% increase). Most reported cases are domestic (31.4% involve cruelty by husbands or relatives) or sexual (7.1% are rape cases).

Even workplace harassment is rising. Complaints under the POSH Act grew from 402 in 2018 to 422 in 2022. Globally too the toll is high – in 2022 about 89,000 women and girls were victims of intentional homicide – and South Asia bears a heavy burden. India, ranked 128th out of 177 countries on women’s security in 2023, continues to see heinous crimes despite legal reforms.

Chart: Reported crimes against women in India climbed from 58.8 to 66.4 per 100,000 women between 2018 and 2022 (NCRB data). This 12.9% rise highlights growing violence and/or better reporting.

Forms of violence against women

Crimes against women take many forms, all rooted in gender inequality. Major categories include:

- Domestic violence – Physical, emotional or sexual abuse by a husband or family member (cruelty under IPC §498A). This is the most common crime: about 31.4% of all reported violence against women in India is “cruelty by husband/relatives”. Such abuse can range from beatings and intimidation to coerced suicide.

- Sexual assault and harassment – Non-consensual acts like rape, molestation and sexual abuse. Rape accounted for 7.1% of crimes against women in 2022, though experts note under-reporting. Outraging a woman’s modesty (molestation) was 18.7% of cases. At the workplace or in public spaces, harassment (now punishable under the 2013 POSH Act) is also widespread.

- Dowry Harassment and Death – Demands for dowry often lead to cruelty and even murder. Despite legal bans, thousands of cases are reported annually. In 2020 India logged about 10,366 dowry harassment cases and 6,966 dowry deaths. Victims may face torture or death when in-laws demand more gifts or money.

- Trafficking and exploitation – Women and girls are trafficked for sexual or labour exploitation. This includes prostitution and bonded labour (IPC 370–372). Many young women are lured or kidnapped into a network of abuse. Under special laws, immoral trafficking and buying/selling of minor girls are recognised offences.

- Child marriage and child abuse – Forced underage marriage and sexual exploitation of minors violates the law (Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, POCSO Act). Adolescent girls are especially vulnerable to rape and forced marriage, which carry their own penalties. Child marriage is officially banned, but enforcement gaps persist.

- Honour killings and witch-hunting – In some regions, women are murdered by relatives for perceived ‘honour’ violations (e.g., marrying outside caste) or accused of witchcraft. These extrajudicial crimes are rooted in superstition and patriarchy. The government has special provisions, but cases still surface in tribal and rural areas.

- Acid attacks – Deliberate pouring of acid (often by rejected suitors or relatives) to disfigure women. Since 2013 acid attacks are a distinct crime (IPC 326A) punishable by 10 years to life imprisonment. However, cases have risen. Media reports cite hundreds of attacks a year. Acid violence is most common in South Asia; Bangladesh’s strict laws have reduced attacks by ~20–30%, but India continues to see many incidents.

- Cyber and online abuse – Digital stalking, harassment, non-consensual sharing of images (‘revenge porn’), and bullying of women online. This emerging threat is covered under IT laws, but enforcement is still developing. A recent NCRB category ‘cybercrime against women’ reflects this growing trend.

These forms often overlap and compound one another. For example, a woman facing dowry torture may also be raped or threatened with acid. Children can be victims of sexual abuse at home or trafficked. In India, the United Nations notes that gender-based violence includes all these facets – domestic abuse, dowry violence, honor crimes, acid attacks and more. Each form leaves deep scars on survivors and families.

Impact of violence

The consequences of crimes against women are devastating on multiple levels. Physically, victims suffer injuries, chronic pain, disabilities or unwanted pregnancies. Psychologically, they face trauma, depression, stigma and loss of trust. Many survivors struggle with social isolation and economic hardship, as abuse often destroys livelihoods.

According to public health experts, these individual impacts add up. Violence increases women’s health problems, can lead to STIs or death, and even disrupts entire families. At a societal level, gender-based violence violates basic human rights and undermines development goals. It reduces women’s participation in education and the workforce, cutting productivity. UN reports warn that such violence hinders progress on Sustainable Development Goals (like good health, equality, and decent work).

In India, these impacts are compounded by social and economic factors. Many women lack financial independence or legal awareness, making it hard to escape abusive situations. For instance, under many custom and inheritance norms women cannot claim property, and most work in informal jobs without protection.

The National Family Health Survey (2019–21) found 29.3% of women aged 18–49 have experienced spousal violence in their lifetime. Even if crimes are reported, justice can be slow; patriarchal attitudes often blame victims or discourage their testimony. As a result, many cases never enter the official record at all. Experts note that cultural shame and fear of retaliation are huge barriers to reporting.

Real stories illustrate these hardships. Laxmi Agarwal, for example, was just 15 when a jilted man threw acid on her. She spent years in surgery and faced social stigma, even as she tirelessly campaigned for stricter acid laws. Her efforts (and similar ones by activists) led the Supreme Court in 2013 to impose tighter controls on acid sales and higher compensation for survivors. Today Laxmi heads a foundation that helps fellow survivors rebuild their lives. Her courage shows how victims can become voices for change but it also underscores the brutality of these crimes.

Legal protections and government schemes

India has a broad legal framework to address violence against women. Key laws include:

- IPC 498A (Cruelty by husband/relatives) – Penalises physical or mental cruelty to women in marriage, including dowry demands.

- Protection of women from Domestic Violence Act (2005) – Allows survivors to seek protection orders, residence rights, and maintenance from abusive partners.

- IPC 304B (Dowry Death) – Punishes death of a bride within 7 years of marriage if dowry harassment is proven.

- Dowry Prohibition Act (1961) – Bans requesting or giving dowry gifts; harassment under this Act saw over 13,000 cases in 2019.

- POCSO Act (2012) – Protects children (including girl children) from sexual offences with stringent penalties.

- Criminal Law (Amendment) Acts (2013, 2018) – Enacted after high-profile cases, these strengthened rape laws (including fast-track courts, death penalty for gang-rape), and clarified offenses like stalking and acid attacks.

- Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace Act (2013) – Mandates employers to prevent and address sexual harassment on the job (though social awareness and complaint rates remain low).

Beyond laws, the government runs many schemes and support systems. For victims of violence, One Stop Centres (also called Sakhi Centres) were launched in 2015 to provide integrated aid. These centers offer medical care, legal counselling, police liaison, and temporary shelter under one roof for survivors of domestic or public violence. The Ministry of Women & Child Development reports over 708 One Stop Centres were operational by 2022, assisting 540,000 women nationwide.

Other initiatives include a 24×7 Women’s Helpline (1091/181) and the unified emergency number 112 for immediate assistance; Beti Bachao Beti Padhao campaign to promote girl child welfare; Safe City Projects (in major cities) installing CCTV and better lighting; and Mahila Adalats (special women’s courts) for resolving complaints quickly. Police stations also now have Women’s Help Desks for gender-sensitive handling of cases.

Funds from the Nirbhaya Fund are used for training investigators, setting up trauma rooms, and providing forensic kits to speed up rape case trials. The National Commission for Women (NCW) itself operates a dedicated WhatsApp helpline (72177-35372) to report violence. All these measures aim to plug gaps in the system.

Despite the laws, enforcement is uneven. Experts urge further action. Educational campaigns in schools, community-level gender-sensitisation, and better funding for support services. For example, the Women’s Commission notes that combining legal aid with job training and counselling is crucial to help survivors rebuild independent lives. In other words, legal remedies must go hand-in-hand with social change to truly curb these crimes.

Crimes against women: India vs. Global context

While violence against women is universal, its shape and prevalence vary by region. Globally, WHO data indicate that about 30% of women experience intimate partner or sexual violence in their lives. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) reported nearly 89,000 gender-related homicides of women/girls worldwide in 2022. South Asia bears a disproportionate share of certain crimes.

For example, India – like neighbouring Pakistan and Bangladesh – has historically high rates of acid attacks and honour killings. Notably, Bangladesh’s strict acid laws have led to a 20–30% decline in attacks, a success India still strives for.

India’s Women Peace and Security Index rank (128/177 in 2023) trails most developed countries. Factors include continuing social inequality, access to justice, and political representation. In some metrics India outperforms its neighbours. According to the 2021 National Family Health Survey, the child sex ratio (females per 1000 males) improved to 1020, indicating progress against female infanticide.

However, in crime statistics the picture is worrisome. The NCRB found criminal cases against women per 100,000 population are significantly higher in states like Delhi (144.4) and Haryana (118.7) than the national average.

It’s clear that India’s challenge is both similar to and worse than global trends. Like many countries, India struggles with under-reporting and stigma. But deeply rooted gender bias and large population density mean even a small percentage of unreported crimes translates to very high absolute numbers.

Comparing international data underscores that every country has a stake in solutions – from enforcing international conventions to sharing best practices. India’s recent improvements in laws and awareness are positive, but the on-ground reality still lags behind many peers.

Empowering women and girls – The role of Smile Foundation

Stopping crimes against women requires prevention and empowerment, not just punishment. Smile Foundation addresses root causes by empowering women and girls in vulnerable communities. Our flagship Swabhiman programme (launched in 2005) offers a holistic mix of health, nutrition, and livelihood support to marginalised women.

Swabhiman helps women start microenterprises, learn financial literacy, and access healthcare. For instance, Smile provides skill training (e.g. sewing, farming) along with seed capital, so beneficiaries can earn their own income.

Image: A Smile Foundation beneficiary uses vocational training (here, tailoring) and support to build a livelihood. Programmes like Swabhiman equip women with skills, tools and awareness, enabling them to earn independently.

Smile’s approach ties into broader development goals by combining reproductive health awareness with entrepreneurship, Swabhiman makes women more self-reliant. In practical terms, nearly 190,000 women across six states have benefitted from Swabhiman in recent years. These women learn to plan family health, start savings, and even lead local groups. For example, in Maharashtra Smile recounts how Ishwati – once a daily-wage laborer – received seeds, a pump and training to start farming. She now earns about ₹10,000 from selling her crops, supplementing her family’s income and inspiring others in her village. Stories like hers show that when women gain skills and confidence, they can resist exploitation and lift their families out of poverty.

Smile also focuses on educating and empowering girls. Our She Can Fly initiative (alongside other campaigns) encourages girls to stay in school, get vocational training and focus on health and nutrition. Educated girls are far less likely to be married off early or fall prey to traffickers. By promoting financial literacy and life skills, Smile helps girls become change agents in their own communities. Together, these programmes aim to reduce vulnerability. We believe that an informed, skilled woman is better able to assert her rights and avoid abusive situations.

For donors and policymakers, Smile’s impact is a model worth supporting. The organisation’s integrated work – combining nutrition programmes, reproductive health camps, and women’s entrepreneurship – addresses several risk factors for violence. Recognising this, Smile aligns with national schemes (like Anemia Mukt Bharat and Poshan Abhiyan) to strengthen government initiatives.

Our partnerships have helped set up community kitchens, support mothers’ groups, and equip health workers to be more responsive to women’s needs. In short, Smile Foundation illustrates how empowerment and awareness can complement laws to actually reduce crimes against women.

What can be done

Experts emphasise a multi-pronged approach by educating boys and girls about gender equality, sensitising communities, strictly enforcing laws, and expanding support for survivors. Engaging youth is vital – curricula and media must challenge stereotypes that condone violence. Policymakers must ensure funding for women’s shelters, legal aid, and healthcare is adequate and effectively used. The public can play a role by supporting and volunteering with NGOs like Smile that empower at-risk women.

Real change also needs cultural shifts. Indian society must move beyond protective attitudes to genuinely value women’s autonomy. Everyday citizens can help by speaking out against harassment, supporting survivors, and demanding accountability. Even small steps – a bystander intervening in public harassment, or communities educating young couples about mutual respect – can add up.

In India and around the world, ending crimes against women will require everyone’s effort. The legal toolbox is in place, but enforcement and social support must be strengthened. Programmes like Smile Foundation’s Swabhiman and She Can Fly show that empowering women economically and socially can break the cycle of abuse. By combining legal remedies with education and opportunity, society can turn the tide – ensuring every woman and girl can live free of violence.

Sources: Official crime data (NCRB, NFHS) and expert analyses; global stats (WHO, UNODC); Smile Foundation reports and case studies; academic and media reports.