India is at the epicentre of a diabetes epidemic. With over 101 million people currently diagnosed and nearly 136 million pre-diabetic, the country has the second-largest population of people with diabetes in the world—second only to China. The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) warns that these numbers could rise dramatically if structural interventions are not implemented swiftly.

While public discourse on non-communicable diseases (NCDs) has increased in recent years, India’s strategy for diabetes remains reactionary and overly concentrated on tertiary care. As the burden grows, the focus must shift decisively toward prevention, early detection, and community-based management where a robust primary healthcare system can serve as the first and most important line of defense.

This article examines India’s diabetes crisis, the socioeconomic, and health system factors exacerbating it, and why strengthening primary healthcare is the most sustainable and inclusive response.

Diabetes in India: The numbers should alarm us

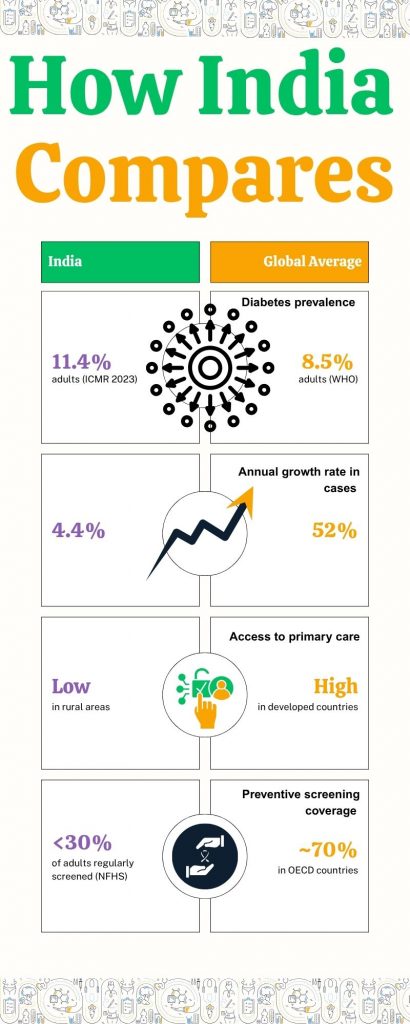

Diabetes is no longer a disease of the wealthy or elderly. Increasingly, it affects younger age groups and lower-income populations. The Indian Council of Medical Research–India Diabetes (ICMR-INDIAB) study published in The Lancet (2023) uncovered troubling data:

- 11.4% of Indians now live with diabetes (up from 7.1% in 2012)

- Nearly 15.3% have prediabetes

- Urban areas continue to show higher prevalence, but rural areas are catching up rapidly

- Southern states like Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Puducherry have the highest rates (19%+)

Compounding the crisis is the lack of awareness. Nearly 45% of individuals with diabetes remain undiagnosed. Among those diagnosed, only 7% have their blood sugar, blood pressure, and cholesterol under control, key factors in reducing complications.

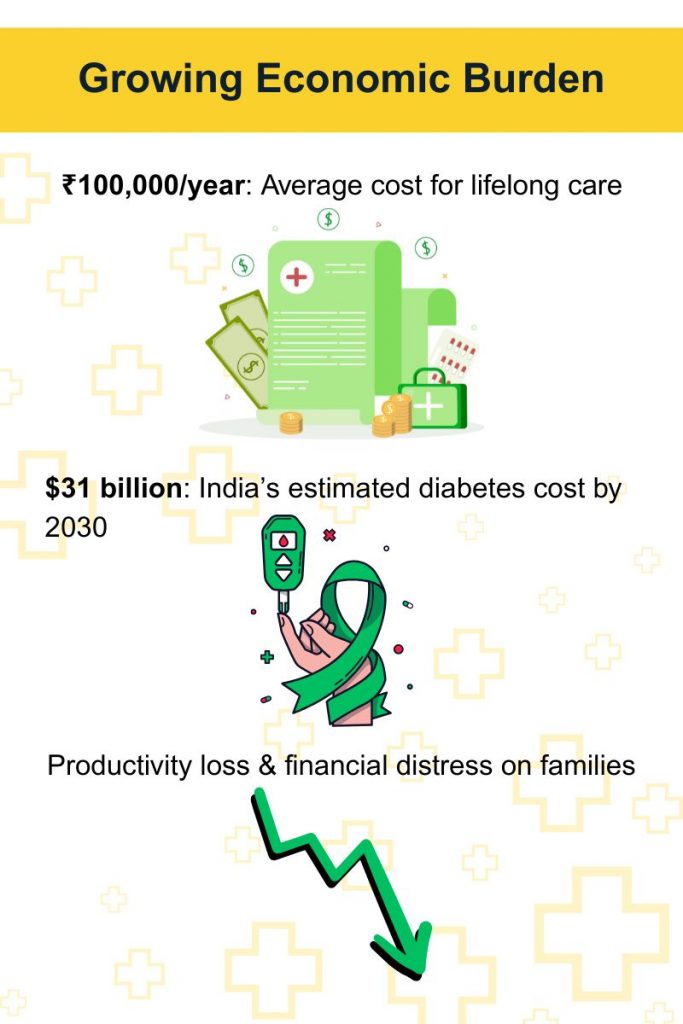

The socioeconomic toll of Diabetes

A 2020 study by the Public Health Foundation of India estimated that households in urban slums spend up to 25% of their income on diabetes-related expenses. The annual direct cost of treating diabetes per person ranges from ₹15,000 to ₹40,000, depending on complications.

India also loses billions in productivity due to poorly managed NCDs. The WHO estimates that between 2012 and 2030, India will lose $3.5 trillion in national income due to NCDs like diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer.

For daily wage workers, women caregivers, and rural households, the impact is both medical and intergenerational. A parent’s loss of income due to untreated diabetes can affect children’s nutrition, education, and well-being. For many, diabetes becomes a poverty trap.

Why primary healthcare must be the frontline

India’s current health response is largely hospital-centric. But 70% of Indians seek care in the private sector, often at high personal cost. Primary Health Centres (PHCs) and Sub Centres are ill-equipped to screen for or manage diabetes.

This creates a dangerous cycle of delayed diagnosis, increased complications, and seeking help only when symptoms become acute. Hospitals are overwhelmed, and early prevention opportunities are lost.

Primary healthcare, if strengthened, offers a cost-effective, community-centric alternative.

Here’s why primary care matters:

- Early detection and screening: Simple glucose monitoring and risk profiling can be done by trained nurses or ASHAs at the village level.

- Continuity of care: Chronic diseases require regular follow-ups. A trusted local health worker can monitor patients regularly and ensure medication adherence.

- Lifestyle counselling: Behaviour change communication on diet, exercise, tobacco cessation is more effective when rooted in local cultural contexts.

- Cost efficiency: Community-based models are significantly cheaper than hospital admissions or dialysis for complications.

- Integrated NCD care: Primary healthcare workers can manage multiple risk factors like hypertension, obesity, and tobacco use—all linked to diabetes.

What Is holding primary healthcare back?

Despite ambitious schemes like Ayushman Bharat and Health & Wellness Centres (HWCs), India’s primary care system remains underfunded and understaffed.

- India spends only 1.9% of GDP on healthcare

- Community health centres have a shortfall of 4578 surgeons, followed by 4087 OB&GY, 4499 physicians and 4425 paediatricians.

- HWCs, though conceptually strong, face infrastructural, workforce, and medicine stock-out issues

Moreover, primary care still struggles with digital integration, referral mechanisms, and community trust, especially when it comes to NCDs that are invisible in their early stages.

Global comparisons for Diabetes: What India can learn

Other low- and middle-income countries offer models of how to integrate diabetes care into primary health.

- Thailand: Uses village health volunteers to conduct home-based glucose checks and lifestyle counselling

- Brazil: Its Family Health Strategy covers NCDs through community teams, reducing hospital admissions

- Cuba: Every citizen is attached to a family doctor; diabetes care is embedded in routine check-ups

India need not reinvent the wheel. It must adapt global best practices with a hyper-local lens taking into account caste, gender, and economic inequities.

The role of technology and innovation for confronting Diabetes in India

India’s digital health stack, including the Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission (ABDM), has immense potential to transform diabetes care:

- eSanjeevani teleconsultations can bring specialists to remote villages

- mHealth apps can aid self-monitoring for literate youth

- AI algorithms can identify high-risk individuals based on health records

However, tech must be paired with grassroots capacity. A mobile app cannot replace a motivated ASHA who knows her community’s health profile. Digital must be inclusive, not aspirational.

Smile Foundation’s community-led health model

Smile Foundation’s Smile on Wheels mobile medical unit programme and community health initiatives, exemplifies how non-profit models can fill systemic gaps.

- Rural outreach: Mobile health vans reach underserved blocks in states like Uttar Pradesh, Odisha, and Rajasthan, offering NCD screenings and awareness sessions.

- Health education: Community sessions on healthy eating, exercise, and avoiding tobacco are delivered in local languages.

- Women-centric care: ASHA and SHG women are trained to identify early signs of diabetes and refer cases.

- Tech integration: Some projects use digital tablets for maintaining community health records and monitoring follow-ups.

These models prove that where trust, relevance, and access align, primary care becomes powerful.

Policy recommendations: What needs to happen next

- Invest in frontline workers: Increase honorariums for ASHAs and ANMs, and train them in NCD management.

- Decentralise services: Ensure PHCs have glucometers, test strips, and trained personnel. Empower local governance to monitor service delivery.

- Public-private partnerships: Leverage CSR, NGOs, and health tech startups for scalable diabetes solutions.

- Incentivise prevention: Link community health indicators (like blood sugar control) to funding for local health institutions.

- Mass media campaigns: Normalise diabetes conversations. Use radio, local influencers, and vernacular media.

Make Primary Healthcare the Hero of Diabetes control

When diabetes affects millions of working-age Indians, it slows down productivity, depletes household savings, and strains public health resources.

India’s long-term solution cannot lie in more hospital beds or tertiary facilities. It lies in every village, in every urban slum, and in the hands of trained, trusted frontline workers.

A reimagined primary healthcare system, with diabetes at its core, will not just save lives, it will empower communities, reduce inequality, and deliver on the promise of health for all.