In Joynagar and Kadamtoli — two villages in Bangladesh’s Kachua upazila — the closure of a single school did more than halt classes. It ripped a seam in the community life. The effects are not contained to the children who once filled its benches. They spread into homes, businesses and the ambitions of a generation that will now come of age without the anchor of a nearby school.

We talk a lot about access to education in the abstract — about literacy rates and enrolment figures, about Sustainable Development Goal 4’s promise of inclusive, quality education for all by 2030. But the conversation rarely lingers on the lived reality of what happens when that access is physically removed. This is the story we avoid because it forces us to confront the uncomfortable truth that losing one rural primary school can erase decades of progress, not just for individual children but for entire communities.

A symbol of hope, born from the ground up

The story of this school began not with a government budget but with a gift of land. In 2004, local social worker Abdur Rahim Patwary and other community members pooled 20 decimals of land so children could learn without walking miles. It was a humble building — three classrooms, a handful of teachers, 200 eager pupils. For a brief time, the school was a living proof of what collective action can achieve.

Then, two years later, the money ran out. The bureaucratic support never arrived. And one day, the gates closed. No formal announcement, no relocation plan. Just an absence that settled into everyday life, quietly rearranging futures.

Primary school education interrupted, lives derailed

When a rural primary school closes, children don’t simply move to the next nearest one. In practice, it means longer walks — often along unsafe or flood-prone routes — or prohibitive transport costs. Parents, weighing the risks, sometimes decide it’s safer or cheaper to keep children at home.

For girls, the consequences are especially severe. In the absence of a local school, concerns about safety and propriety rise. Early marriages become more likely. Household work replaces homework. Over time, the educational gap between boys and girls widens, entrenching inequality for another generation.

And the impact is not only academic. Rural schools are often the hub for vaccination drives, midday meal schemes and community meetings. Their closure cuts off these lifelines, leaving a void in both services and social connection.

The quiet economics of school closures

Education experts often frame school closures as an educational crisis. But they’re also an economic one. In Joynagar and Kadamtoli, families with means began migrating to areas with better schools. Property values dipped. Local shops saw fewer customers. The absence of young families made it harder to justify investment in roads, water systems or even internet connectivity.

This is the downward spiral rarely captured in policy debates: the loss of a school accelerates rural decline. It’s not just that children lose lessons; it’s that entire villages lose reasons to stay, invest and grow.

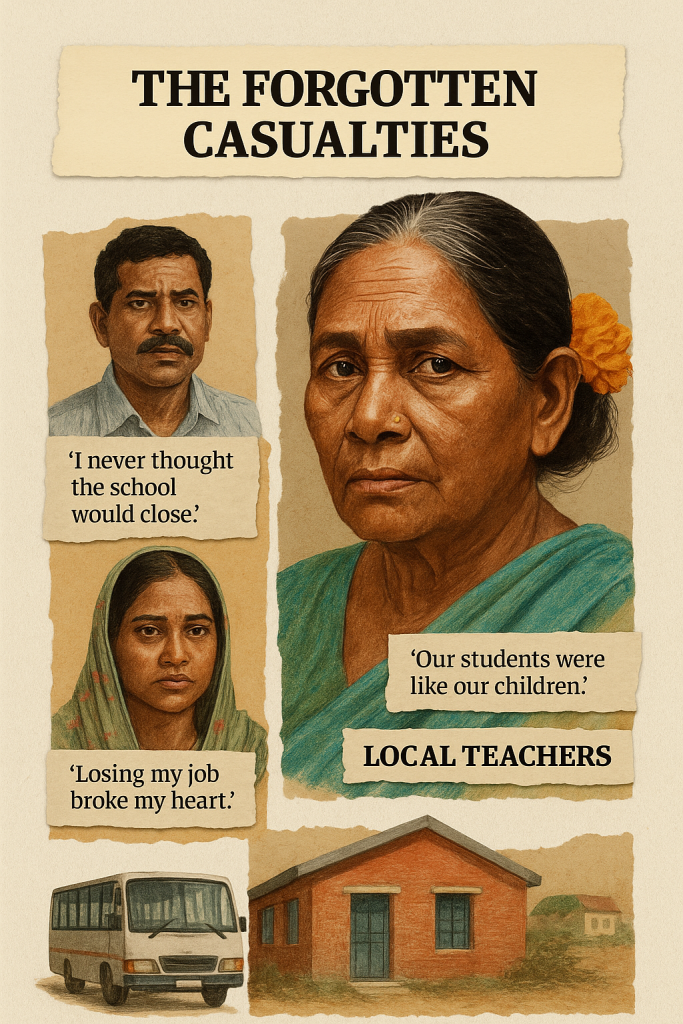

The teachers left behind

When the school closed, its teachers — once community pillars — were left jobless. Many had no choice but to move away or take up work unrelated to education. The loss isn’t just about headcount; it’s about mentorship, continuity and the trust built between educators and families over years.

A national problem in microcosm

The case of Joynagar and Kadamtoli is not an anomaly. Across South Asia, rural school closures are becoming more frequent — often justified under the logic of “rationalisation” or budget efficiency. But these closures disproportionately hit low-income and marginalised communities, the very groups most at risk of being left behind.

Globally, UNESCO estimates that 272 million children and young people are out of school — a 3% rise since 2015, reversing hard-won gains. In countries like India and Bangladesh, where rural populations remain large, the loss of a local school can set back not just educational attainment but public health, gender equality and economic resilience.

The human cost behind the numbers

The children affected by school closures don’t fade neatly into statistics. In Joynagar, one girl now spends her mornings collecting water instead of learning to read. A boy who used to dream of becoming a doctor now helps his father in the fields. These shifts may seem small to outsiders, but they shape trajectories in permanent ways.

When a child misses the foundation years of education, catching up becomes exponentially harder. Illiteracy limits job opportunities, reduces awareness of rights and keeps families locked in poverty. The deprivation is quiet, almost invisible to those outside the village — but its effects will echo for decades.

The missing safety net

It shouldn’t take the personal intervention of a new upazila education officer to reopen a school. Yet in Joynagar, that’s exactly what locals are hoping for. They’ve submitted a petition. The officer has promised a site visit. It’s a small step, but it reveals the fragility of rural educational infrastructure: without sustained funding and oversight, these institutions can vanish overnight.

National education policy often assumes that if a school closes, children will simply transfer elsewhere. But this ignores the realities of rural geography, poverty and gender norms. What’s missing is a mandatory safety net: a guarantee that no community will be left without a functioning primary school within accessible distance.

A matter of justice

We often talk about education as a human right. But rights are only as strong as the systems that uphold them. Closing a rural school without a plan for immediate replacement is not just a logistical oversight — it’s a breach of that right.

The irony is painful: in a world obsessed with digital progress and AI breakthroughs, there are children counting on their fingers because they don’t own a notebook.

From loss to action

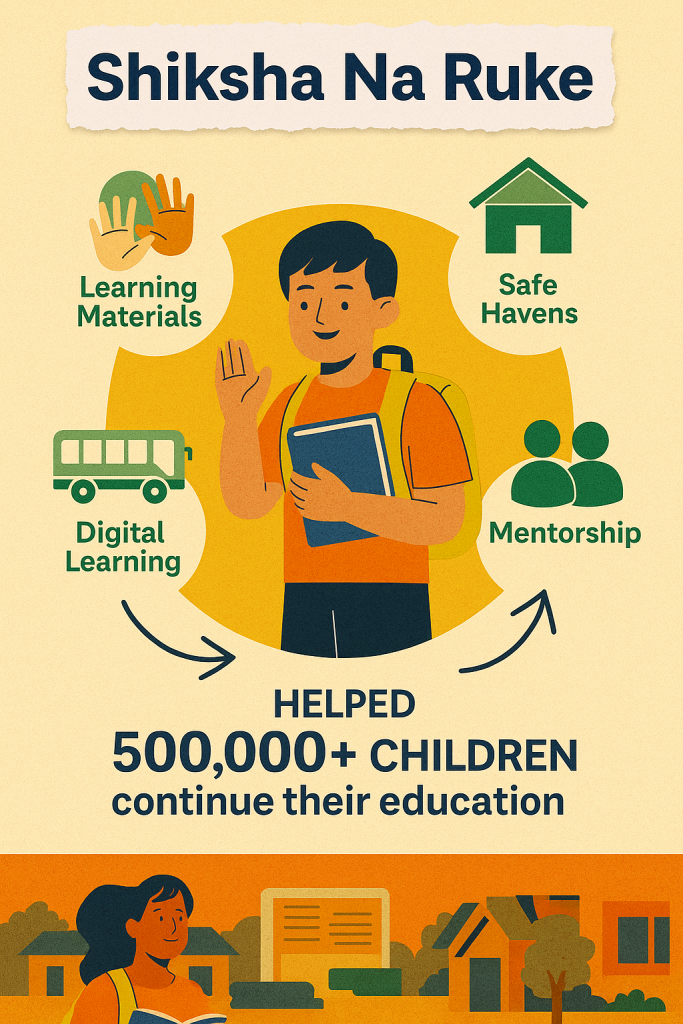

Not all is despair. Initiatives like Smile Foundation’s Shiksha Na Ruke are stepping into the breach, helping children in difficult circumstances continue their studies through community-based learning kits, mentorship and alternative learning centres. But these are stopgaps, not substitutes for a functioning public education system.

If we are serious about meeting SDG 4, the starting point is deceptively simple: keep existing schools open. Fund them adequately. Staff them with trained teachers. Make closure the absolute last resort, not the first budget-cut option.

Because when a school disappears, the loss is not contained to a building. It’s in the wedding of a 14-year-old girl who might have been a teacher. It’s in the empty shop on the village’s main road. It’s in the silence where children’s voices used to rise in chorus, reciting lessons they believed would take them somewhere.

If you are a policymaker: write protection clauses into education budgets. If you are a philanthropist or corporate leader: fund not just new schools but the survival of existing ones. If you are a citizen: ask your elected representatives what they are doing to prevent closures in the most vulnerable areas.

Because in Joynagar and Kadamtoli, the community’s future is hanging on whether those gates will ever open again. And in thousands of villages like them, the story is the same.

The question is whether we’ll notice before the silence spreads.