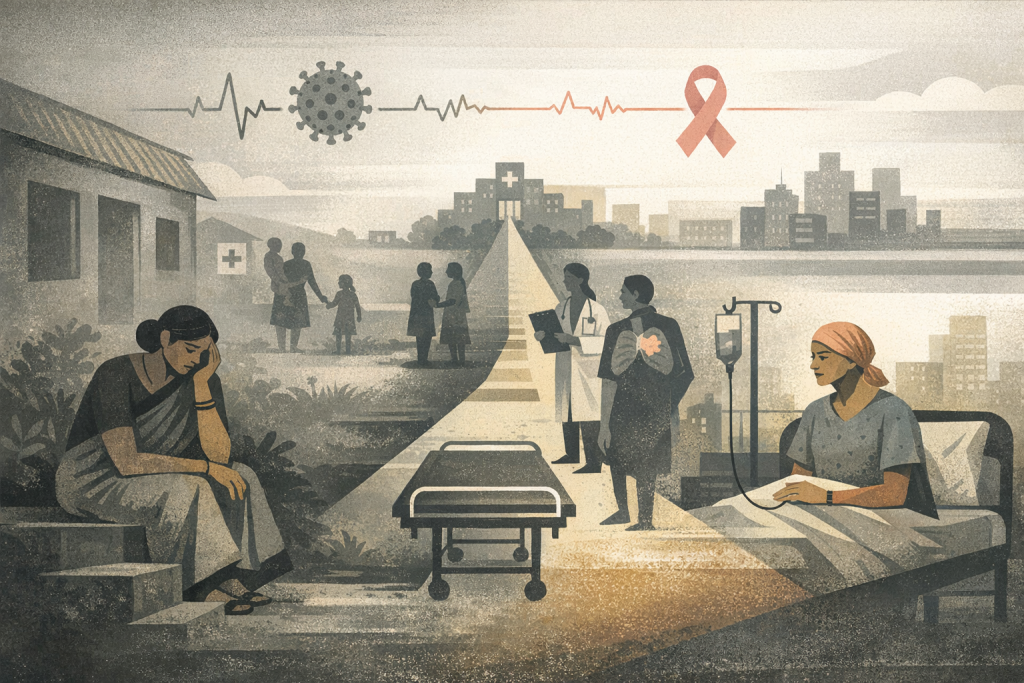

Cancer is no longer a distant diagnosis in India. It is increasingly a lived reality, and for women, it carries layers of vulnerability that extend far beyond the disease itself.

Today, more than seven lakh women in India are diagnosed with cancer every year. Breast cancer has emerged as the most common cancer among Indian women, followed closely by cervical cancer. While medical science continues to advance, the social realities surrounding women’s health often determine outcomes long before treatment begins.

Cancer, for many women, does not begin in the hospital. It begins in silence.

The Changing Face of Women’s Cancer in India

India is witnessing a profound epidemiological shift. As infectious diseases decline comparatively, non-communicable diseases, including cancer, are rising steadily.

Breast Cancer: An Urban Surge

Breast cancer now accounts for nearly one in four cancers diagnosed among Indian women. Increasing urbanization, delayed childbirth, reduced breastfeeding, sedentary lifestyles and rising obesity have contributed to this surge.

More concerning is the age pattern. A significant proportion of cases are diagnosed in women between 30 and 50, often at the peak of their economic and caregiving responsibilities.

Cervical Cancer: A Preventable Burden

Cervical cancer remains one of the leading cancers affecting women, particularly in rural and lower-income communities. Unlike many other cancers, cervical cancer is largely preventable through HPV vaccination and early screening. But awareness and access remain uneven.

A Double Burden

India faces a dual challenge:

- Infection-linked cancers such as cervical cancer.

- Lifestyle-linked cancers such as breast and colorectal cancer.

This duality reflects both development gains and emerging risk transitions.

The Late Diagnosis Problem

One of the most persistent challenges in India is late-stage detection.

A large proportion of breast and cervical cancers are diagnosed at Stage III or IV. By then, treatment is more complex, more expensive and survival outcomes are lower.

Why do women present late?

- Limited awareness of early symptoms

- Fear of diagnosis

- Stigma around reproductive and breast health

- Financial dependency

- Prioritising family needs over personal health

In many households, women delay seeking care until symptoms become unbearable.

By then, the disease has progressed.

When Illness Becomes Economic Shock

Cancer is not only a medical event — it is a financial and social rupture.

For women in low-income households:

- Treatment expenses can push families into debt.

- Children may drop out of school.

- Household income declines sharply.

- Caregiving burdens increase for older daughters.

The economic shock often compounds existing vulnerabilities.

Women’s health, therefore, is deeply tied to household stability.

Screening: The Missed Opportunity

India’s national health programme includes population-based screening for breast and cervical cancers for women above 30 years. But screening coverage remains inconsistent across states and districts.

Early detection saves lives. A simple clinical breast examination or cervical screening can detect abnormalities before they become life-threatening.

But screening depends on:

- Access to primary healthcare

- Trust in the system

- Regular outreach

- Follow-up mechanisms

Without continuity, screening loses effectiveness.

HPV Vaccination: A Turning Point

Cervical cancer offers a powerful opportunity for prevention. The introduction of an indigenously developed HPV vaccine has opened a new chapter. With adequate scale-up and awareness, India can significantly reduce future cervical cancer incidence.

However, vaccination campaigns must be accompanied by:

- Community sensitization

- Parental awareness

- School-level outreach

- Trust-building efforts

Prevention must be both medical and social.

The Rural–Urban Divide

Cancer patterns differ across geography:

- Urban women face rising breast cancer incidence.

- Rural women experience higher cervical cancer mortality.

Healthcare infrastructure remains uneven. Rural patients often travel long distances for oncology services and referral systems may be fragmented which leads to accumulation of delays.

Inequity shapes survival.

The Role of Community-Based Health Systems

For many underserved communities, primary healthcare outreach is the first line of defence.

Through Smile Foundation’s mobile healthcare initiative, Smile on Wheels, women receive:

- Basic health screening

- Early detection referrals

- Anaemia checks

- Blood pressure and diabetes monitoring

- Health education sessions

School-based programmes also integrate adolescent health awareness, including menstrual hygiene and reproductive health, which form early layers of cancer prevention literacy.

Preventive health education builds the confidence to seek care early.

Beyond Treatment: The Psychosocial Dimension

A cancer diagnosis often carries stigma and emotional distress. Women may experience:

- Isolation

- Anxiety

- Fear of being perceived as a burden

Community engagement and counselling can reduce fear and encourage early consultation.

Health literacy is not only informational. It is emotional.

The Way Forward

Addressing cancer among women in India requires a multi-layered response:

- Expand screening coverage at the primary care level.

- Scale HPV vaccination nationally.

- Strengthen district-level oncology services.

- Reduce financial barriers through health protection schemes.

- Invest in awareness campaigns tailored to local contexts.

- Integrate nutrition and lifestyle education early.

Women’s cancer cannot be treated solely at tertiary hospitals. It must be addressed upstream — in schools, community centres and primary healthcare systems.

A Development Imperative

When a woman survives cancer, the impact reverberates through her family.

When she does not, the loss is intergenerational.

Cancer among Indian women is not only a health statistic. It is a development issue linked to education, workforce participation, poverty cycles and gender equity.

Investing in early detection and preventive care is not only compassionate policy. It is economically rational.

The path forward is clear: strengthen primary care, reduce stigma, expand prevention and ensure that no woman delays treatment because her health seems less urgent than her responsibilities.

Because when women’s health is protected, families are stabilised. And when families are stabilised, communities thrive.