Every year, millions of Indians pack their bags for foreign universities, hospitals, and laboratories. More than 1.8 million study abroad; hundreds of thousands more settle in richer economies. This global demand flatters India’s education system — but at home, the departures have begun to look like a strategic loss.

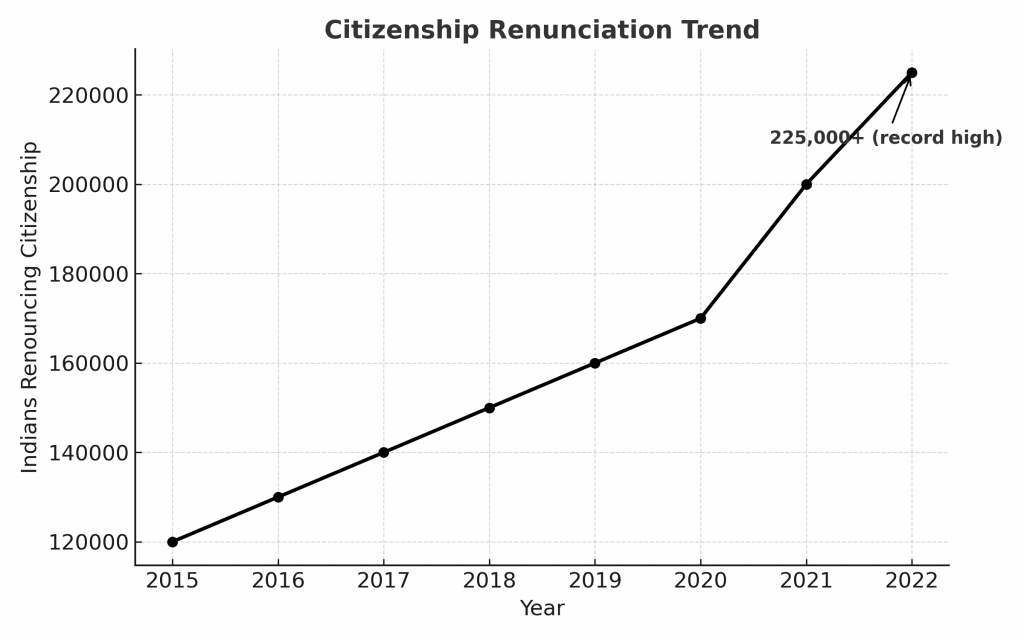

In recent years this outflow of brain drain has reached striking levels. Between 2015 and 2022, an estimated 1.3 million Indians emigrated, many of them doctors, engineers, IT professionals and academics. In 2022 alone, a record 225,000 Indians renounced their citizenship, often to acquire passports of countries like the United States, Canada, Australia, and those in Europe.

This exodus reflects both the global demand for Indian talent and persistent gaps in India’s domestic environment. As India aspires to great-power economic status and self-reliance, the question of how to stem talent loss – or even convert it into “brain gain” – has taken on new urgency.

The scale of India’s talent exodus

By sheer numbers, India’s diaspora is the largest in the world – roughly 20 million Indians were living overseas as of 2020. Not all are highly skilled, but a significant share are professionals and students, and this number is climbing fast. In fact, India now accounts for a third of all international students in major destination countries (U.S., UK, Canada, Australia), a huge jump from just 11% a decade ago.

Every year, hundreds of thousands of young Indians enroll in foreign universities – an educational exodus financed by families back home. Indian households spent about $44 billion in 2024 on overseas education for their children, a figure projected to double to $91 billion by 2030. This includes tuition and living expenses and represents a massive outflow of capital. There is also a steady stream of skilled workers moving overseas for jobs. On average around 2.5 million Indians emigrate each year (of all skill levels), a trend that “threatens India’s growth by depleting its skilled human capital,” as one analysis noted.

The profile of this migrant talent pool spans industries. In technology, Indians comprise a sizeable portion of Silicon Valley’s workforce and startup founders. An estimated one-third of engineers in Silicon Valley are of Indian origin, and Indians have founded or led dozens of “unicorn” tech startups globally. In corporate leadership, Indians punch above their weight: over 10% of Fortune 500 CEOs are Indian-born or of Indian origin, running giants like Google, Microsoft and Adobe.

In medicine, India is one of the largest exporters of doctors and nurses; for example, Indian-trained physicians form a significant part of the workforce in the UK, US, Canada and the Gulf. This outward flow underscores India’s strong education in fields like engineering and medicine – but also raises flags about domestic shortages.

In academia and research, Indian scientists often seek opportunities abroad: India was the second-largest source of foreign science and engineering PhD students in the U.S. in the 2000s and 2010s (after China) and Indian students earned about 13% of U.S. doctorates awarded to foreign nationals in 2018. These figures illustrate the scale at which India’s talent is contributing to other economies and institutions.

Why India’s brightest leave

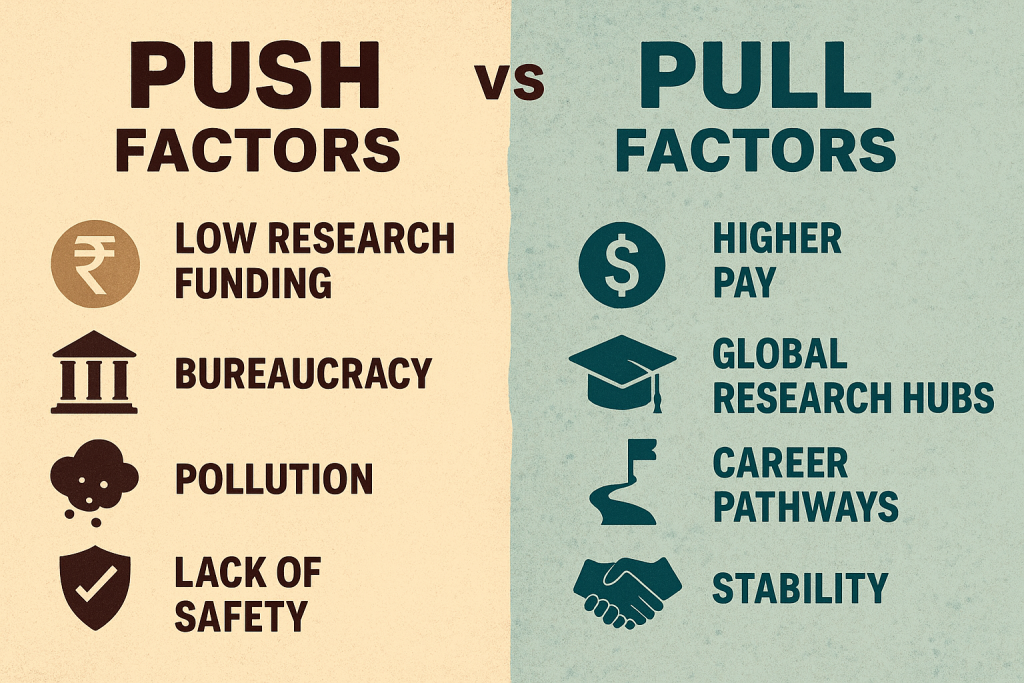

The causes of India’s brain drain are multifaceted, involving both “push” factors at home and “pull” factors from abroad. Surveys and studies consistently point to a mix of economic, professional and quality-of-life motivations driving Indians to migrate. Some of the key reasons include:

- Higher salaries and career opportunities: A talented professional in technology or healthcare can earn significantly more in Silicon Valley or London than in India. Many global companies actively recruit in India – for instance, tech giants like Google and Microsoft hire scores of Indian engineers and Western healthcare systems eagerly accept Indian doctors and nurses. The wage differentials are stark; even Indian IT firms have sometimes facilitated “talent export” by sending employees abroad on projects and H-1B visas. Ambitious individuals often feel that top roles, cutting-edge projects or a fast career trajectory are more accessible overseas.

- Research and academic infrastructure: For scientists, researchers and academics, the allure of world-class labs, abundant research funding and intellectual freedom in the U.S. or Europe is strong. India’s R&D spending has hovered around a low ~0.7% of GDP, trailing far behind advanced economies that invest 2–3% of GDP in research. This translates to fewer research positions and grants at home. A physics or biotech PhD from IIT might head to the West where universities and companies offer state-of-the-art facilities and support for innovation. The limited availability of postdoctoral and faculty positions in India’s universities and national labs also pushes many freshly minted Indian PhDs to continue their careers abroad.

- Quality of life and public services: Many emigrants cite better living standards abroad – everything from reliable infrastructure to cleaner air. Big Indian cities struggle with problems such as pollution, traffic congestion and strained public services. For instance, air quality in Delhi or Mumbai often exceeds safe limits, which is a deterrent for those who can choose a life in cleaner environments. Additionally, concerns about public safety and governance play a role. A study of migrating healthcare professionals noted that personal safety, law and order and environmental conditions are significant in the decision to settle abroad. Countries like Canada and Australia actively market themselves to skilled immigrants with promises of safe cities, efficient public transport and social benefits, making them attractive to Indian families.

- Education and skill gaps: Ironically, one driver of student exodus is the limited capacity and competitiveness of India’s own education system. Top Indian institutions (IITs, IIMs, AIIMS, etc.) are world-class but can only admit a tiny fraction of applicants. Many students who don’t secure one of those few spots or who can afford it, opt for universities in the U.S., UK or Australia. Others are drawn by specialised courses or interdisciplinary programmes not widely available in India. In some fields, attending a Western university is seen as a fast-track to international careers. Additionally, the high cost or limited quality of certain programmes at home (for example, expensive private medical colleges) pushes students to seek better value abroad. This educational outbound flow has become a major facet of brain drain, as a large share of those who go abroad for studies choose to start careers and settle there after graduating.

- Immigration policies abroad: On the pull side, many developed countries have immigration policies explicitly designed to attract skilled workers. The points-based systems in Canada and Australia, the H-1B work visa in the U.S., and talent visa schemes in European countries all act as magnets for Indian talent. In recent years, Canada has seen tens of thousands of Indian IT professionals and students become permanent residents annually, thanks to its welcoming stance on skilled immigration. These policies, combined with large Indian diaspora communities already established overseas, create a reinforcing cycle inviting more Indians to migrate.

- Entrepreneurial ecosystem: For startup founders and entrepreneurs, certain foreign locales offer easier access to venture capital, mentorship and markets. Silicon Valley’s vibrant ecosystem, for example, has drawn numerous Indian entrepreneurs. While India’s own startup scene has grown (Bengaluru and Delhi are now major hubs), some innovators still leave to incorporate their companies in the U.S. or Singapore to tap global investors and infrastructure. Until very recently, regulations in India made doing business comparatively cumbersome, which led some entrepreneurs to move abroad for a more favourable business climate. High-net-worth individuals have also emigrated for reasons like lower tax regimes or more stable regulations elsewhere – between 2014 and 2018, approximately 23,000 Indian millionaires left the country, according to one World Bank report. This “rich-person brain drain” underscores that beyond scientists or engineers, the wealthy and business elite may also seek greener pastures.

It’s evident that brain drain is not simply individual wanderlust, but rooted in structural issues. As one commentary put it, India must address “the urgent need for systemic reforms” so that talented citizens find educational excellence, economic opportunity and an innovative environment at home. Otherwise, the magnetic pull of developed nations will continue to draw India’s best and brightest away.

The cost of talent loss

The impacts of brain drain on India are profound and multi-dimensional. At the most direct level, every skilled worker or scholar who leaves represents a loss of human capital for the Indian economy. The country effectively subsidises the education and training of these individuals only to see another nation reap the benefits of their productivity. A study on the fiscal effects of emigration estimated that India loses the equivalent of about 0.5% of its gross national income each year due to high-skilled workers moving to the U.S., which is roughly 2.5% of India’s total tax revenue.

In concrete terms, this is a loss of tens of billions of dollars in potential annual economic output and taxes. In the critical IT sector alone, India may be forfeiting $15–20 billion annually by way of talent that contributes to foreign firms and economies instead of domestically. One informal estimate even pegged the overall cost of brain drain at $160 billion per year, which interestingly is about double India’s defense budget. While such figures are hard to pin down precisely, they underscore the massive opportunity cost of educated Indians working abroad.

The innovation deficit is another concern. When top scientists, engineers and entrepreneurs leave, the country loses out not only on their current contributions but on the multiplier effect they could have had – the startups they might have founded, the patents they might have filed, the students they might have mentored. Silicon Valley’s gain in Indian talent has at times been India’s loss in technological leadership. For example, many Indian-origin tech leaders in the West could have been driving innovation in India’s own companies or research labs, had the conditions been right.

A brain drain of researchers can weaken local knowledge networks, as innovative ideas and collaborations flow outwards. It is telling that India, despite its large workforce, still underperforms in high-end innovation metrics (such as patents per capita or research publications) relative to its potential – a gap partly attributable to decades of scientific talent migrating.

Certain sectors feel the pinch of talent loss acutely. The healthcare sector is a prime example and case study in brain drain dynamics. India today has roughly one million active doctors for a population of 1.4 billion, well below the recommended ratio. Yet India has trained many more doctors – a large number have moved to countries like the UK, U.S., Canada and Australia which actively recruit medical professionals. This outflow “mitigates the effects of increased domestic healthcare spending” by creating shortages of specialists and experienced clinicians in India.

For instance, Indian hospitals, especially in rural areas, struggle to hire enough doctors even as Indian physicians serve in large numbers abroad. The nursing workforce shows a similar trend: states like Kerala and Punjab have a tradition of nurses emigrating to the Gulf or West, leading to domestic shortfalls. The result is an uneven health system where certain regions in India remain underserved. Brain drain thus can quite literally be measured in human lives when you consider patients who lack adequate doctors or healthcare workers.

Beyond the immediate economic and service delivery impacts, there is also a psychological and social cost. A persistent narrative of talent leaving can create a sense of pessimism or diminished national confidence. It can also reinforce itself: if young people see their role models and peers all planning to go abroad, they too are more likely to aspire to leave. This can erode the ambition to improve one’s own country.

Moreover, high-profile cases of brain drain – like Indian engineers driving Silicon Valley or Indian scientists in NASA – often spark debates within India about the environment that drove them away. As one policy forum noted, issues like high taxation, bureaucracy and inadequate research infrastructure in India have discouraged some expats from returning and deterred would-be innovators at home. The loss of any single individual might not cripple a nation of India’s size, but cumulatively the talent outflow has meant fewer dynamic job creators, thought leaders and experts on the ground in India.

It’s not all a one-way loss, however. There are also countervailing gains and silver linings from having a large global Indian diaspora – something we explore later. For now, it’s clear that the net effect of brain drain is a serious concern. Recognising these costs has galvanised Indian policymakers and institutions to search for solutions to convert “brain drain” into “brain gain.”

Efforts to reverse the trend

Facing the challenge head-on, India in recent years has launched a multi-pronged effort to retain talent and incentivise its return. The government, academic institutions and even private sector have started addressing the root causes that drive people away – from boosting research funding to improving career prospects. Key initiatives and policy measures include:

- Investing in research & innovation: A core strategy is to build world-class research infrastructure at home so scientists and engineers don’t feel they must go abroad to do cutting-edge work. The Department of Science & Technology (DST) and other agencies have pumped funds into new labs, centres of excellence and grant programmes. For example, DST’s Fund for Improvement of S&T Infrastructure (FIST) programme provides grants to universities to upgrade laboratories. Likewise, a new National Research Foundation (NRF) was established by an Act in 2023 to steer more strategic research funding into Indian institutions. These efforts aim to address the chronic underfunding of R&D. There’s also greater support for innovation and startups: the Startup India initiative launched in 2016 created a seed fund (₹9.5 billion) and a network of incubators across the country. Today, India boasts the 3rd largest startup ecosystem globally (over 100 unicorn startups), indicating growing opportunities for innovators to thrive without leaving.

- Improving compensation and career paths: Recognising that salary differentials drive many away, some Indian sectors have begun offering more competitive packages, especially in tech and academia. Government research institutions introduced schemes like Performance Related Incentive Scheme (PRIS) and flexible promotions to reward productivity. Premier educational institutions (IITs, IISc, AIIMS, etc.) have been granted more autonomy to hire top talent, sometimes at higher pay scales or with modern tenure tracks, to attract global-caliber faculty. There is also discussion of offering tax incentives or easing administrative hurdles for returning professionals, such as fast-tracking visas or providing tax breaks on income for a few years, though concrete policies on this front are still evolving. The private sector, for its part, has seen MNCs establishing R&D centers in India that pay internationally competitive salaries (Google, Microsoft and IBM all have large research labs in India now). If India’s rapid economic growth continues, the gap in salaries and opportunities vis-à-vis the West is expected to narrow, reducing the push factor over time.

- Academic and scientific diaspora programmes: India is explicitly trying to convert brain drain into brain circulation by tapping its diaspora for collaboration and short-term return. A notable effort is the Vaishvik Bhartiya Vaigyanik (VAIBHAV) initiative, a programme to connect Indian-origin scientists abroad with domestic researchers and institutions. Through VAIBHAV, webinars and joint projects have been set up in frontier fields, leveraging the expertise of the diaspora without requiring permanent relocation. Another programme, GIAN (Global Initiative of Academic Networks), invites accomplished foreign and diaspora academics to teach in Indian universities for short stints, exposing students to global knowledge. The Visiting Advanced Joint Research (VAJRA) Faculty programme provides grants for overseas scientists (including non-resident Indians) to spend 3–12 months in India collaborating on research. Unlike permanent return schemes, VAJRA’s goal is to harness global expertise on a flexible basis – effectively importing knowledge even if the expert’s primary base remains abroad. Such exchanges help plug some brain drain gaps by ensuring India’s scholars and students can work with the best minds, no matter where they reside.

- Reverse brain drain fellowships: To actively lure top Indian talent back home, specialised fellowships have been very important. The Ramanujan Fellowship, for example, is targeted at brilliant Indian scientists and engineers under 40 who are working abroad and wish to return. It offers an attractive research grant and salary top-up for five years for those who come to work at an Indian institution. In the last five years, about 550 researchers have returned to India under the Ramanujan Fellowship scheme alone. Similarly, the DBT Ramalingaswami Re-entry Fellowship (run by the biotechnology department) has brought back over 600 Indian biomedical scientists from overseas since its inception in 2007. These programmes effectively act as a brain gain pipeline, targeting Indians who have gained experience in top labs abroad and giving them resources to set up labs in India. Another scheme, INSPIRE Faculty Fellowship, aims to retain recent PhD holders by providing funding to start their independent research career in India instead of going abroad. By mitigating the financial and professional risks of returning, these fellowships have had some success in reversing the brain drain in academia and R&D.

- Education reforms at home: In the long run, improving India’s higher education system is crucial to reducing the need for students to go abroad in the first place. The government’s National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 is a major overhaul aimed at modernising curricula, promoting multidisciplinary learning and expanding capacity at top institutions. Notably, NEP 2020 also proposes allowing top foreign universities to set up campuses in India and forging international collaborations. If implemented, this could give Indian students the option to get a world-class education without leaving the country. The policy also introduced a 5+3+3+4 school structure and more focus on vocational and skill training from a young age. Over time, these reforms seek to produce graduates who are globally competent but also well-integrated into India’s development needs, thus reducing the push factors for emigration. Early signs of progress include a few foreign institutions expressing interest in opening India branches, and some IITs planning overseas campuses which could eventually stem “education drain.”

- Streamlining governance and opportunities: A broader aspect of retaining talent is making India an attractive place to live and work by tackling the governance issues that often frustrate professionals. Reforms to simplify bureaucratic processes, reduce red tape and fight corruption are ongoing; India’s ease-of-doing-business ranking has improved markedly over the past decade (though more at the macro level). Efforts to improve urban living conditions – from smart city initiatives to pollution control measures – though slow, are aimed at addressing quality-of-life concerns. Additionally, the government has been engaging with the diaspora through events like the Pravasi Bharatiya Divas (Diaspora Day) and creating channels for them to invest in India’s development projects. The underlying message is that India is “open for return” and values the expertise and capital of its overseas citizens.

It’s worth noting that some officials have downplayed the severity of brain drain, pointing out that India’s large population and talent base continue to produce many skilled workers. A recent parliamentary statement even claimed “no significant brain drain” has been observed that would adversely affect India’s science and tech progress. But this view likely hinges on the expectation that new initiatives will keep more talent at home.

Indeed, if India successfully implements these policies – better research funding, quality education expansion, diaspora collaboration and a friendlier business environment – it can create a virtuous cycle where fewer people feel compelled to leave and some who left choose to return, thus transforming brain drain into brain gain.

Grassroots education and the talent pipeline

Reversing brain drain is not only about enticing top scientists or corporate leaders to stay; it also requires nurturing the next generation of talent from the ground up. Analysts argue that brain drain reflects a systemic failure to fully develop and utilise talent within the country. That failure often begins at the earliest stages of education. Many bright individuals in India never get the opportunity to become high-skilled workers in the first place due to disparities in primary and secondary education, especially in rural and under sourced areas.

Strengthening the grassroots education ecosystem is therefore a key long-term strategy to combat brain drain. The logic is twofold: first, a larger and more equitably educated population means India can afford to lose some talent and still have plenty at home; second, individuals who are deeply rooted in their communities and empowered from a young age may be more inclined to contribute locally rather than seek validation solely abroad.

Community-based initiatives have shown promise in this regard. For example, the Smile Foundation’s Empowering Grassroots programme works with over 500 community-based organisations to improve schooling, nutrition and mentorship for children in rural villages, urban slums and tribal regions. By investing in early education, life skills and local role models, such programmes aim to produce a generation of achievers who have strong ties to their home communities.

The Foundation’s Mission Education initiative provides not just academics but also healthcare and nutrition to tens of thousands of children from marginalised backgrounds. The impact of these efforts is seen in improved learning outcomes and higher aspirations among students who otherwise might have been left behind. Crucially, these grassroots programmes also instill a sense of social responsibility and confidence in youth.

A student from a village who succeeds through community-supported schooling may feel a commitment to give back or build something in their hometown, rather than simply join the urban migration rat-race or go abroad. In essence, community schooling and mentorship can create socially rooted, resilient citizens who see viable futures in India.

This approach addresses a subtle facet of brain drain: the narrative of success. If success is consistently portrayed as “going to America” or working in a foreign multinational, young talent will gravitate to that image. But if success stories emerge of innovators and leaders who arose from rural India and stayed to improve their communities, it broadens the imagination of what is possible domestically. There are already examples – entrepreneurs building startups in smaller Indian cities, NGOs led by foreign-educated Indians who returned, local governance champions, etc.

Scaling up grassroots capacity-building can multiply these examples. Over time, bolstering educational equity (more quality schools, teachers and scholarships across India) will enlarge the talent pool and reduce the feeling that one must escape India to fulfill one’s potential. It’s a slow solution, but a sustainable one for long-term brain gain: ensuring India’s intellectual capital is grown and retained from the bottom up, not just retained at the top. As the Economist might put it, the country needs not only world-class universities but also world-class primary schools, so the brightest minds of the next generation see a future in India at every stage of their development.

The diaspora dividend: From brain drain to brain bank

While brain drain poses challenges, India’s global diaspora also represents a tremendous asset – a “brain bank” that India can draw upon. The 32-million-strong Indian diaspora (including people of Indian origin) has achieved remarkable success overseas and many remain emotionally and economically connected to India. One clear benefit is remittances: India has been the world’s top recipient of remittances for over a decade. In 2022, the Indian diaspora sent home an unprecedented $111 billion in remittances, equivalent to about 3.3% of India’s GDP. This is larger than India’s earnings from IT exports or any single category of export. These inflows help stabilise India’s balance of payments and support millions of families.

Notably, about 36% of these remittances came from high-skilled Indian migrants in the U.S., UK and other high-income countries – a testament that even many well-educated Indians abroad send money to support parents, invest in property or fund charities at home. On the other hand, less-skilled migrants in the Gulf contributed around 28% of remittances. In sum, what India loses in direct talent, it partly gains back in financial flows from its overseas citizens.

Remittances to India reached $111 billion in 2022 – by far the largest in South Asia – but as a share of GDP (3.3%) they are lower than smaller countries that rely more on labour migration.

Beyond money, the diaspora boosts India’s soft power and global influence. Indian-origin CEOs of global companies, for instance, have often acted as unofficial ambassadors of India’s talent to the world. The likes of Sundar Pichai (Google) or Satya Nadella (Microsoft) bring visibility to India’s strengths in tech and management. Diplomatically, countries with a strong Indian diaspora (like the U.S., UK, Canada) tend to have interest groups and caucuses that lobby for good relations with India. Culturally, the spread of Bollywood, yoga and Indian cuisine worldwide owes much to diaspora communities acting as cultural carriers. All of this strengthens India’s global standing in ways that are hard to quantify but valuable.

The concept of “brain circulation” is gaining traction as a way to turn brain drain into an advantage. Instead of a one-way loss, India can benefit if its overseas talent remains engaged and circulates knowledge back. There are numerous examples of this: Indian professors in the U.S. co-authoring research papers with colleagues in India; successful Indian entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley mentoring or investing in Indian startups; doctors of Indian origin abroad conducting free medical camps or training sessions in India; and the returnees who come back with new skills.

In fact, the rise of India’s IT and outsourcing industry in the 1990s and 2000s was catalysed by diaspora professionals who returned or built business bridges – the founders of major IT firms and many venture capital funds had international experience. Today, the Indian startup scene sees significant funding from diaspora investors. The Global Innovation Index rankings of recent years have noted India’s progress and attribute part of it to the knowledge linkages of its diaspora scientists and engineers. A fascinating observation is how China leveraged its diaspora: many Chinese-origin scholars abroad began citing and collaborating with China-based researchers, boosting China’s scientific output. India is trying a similar approach, encouraging its scientists overseas to contribute to domestic research from afar.

Moreover, not all who leave are gone forever. A trend of reverse migration or “brain gain” has begun in small numbers. Some Indian professionals, after a decade in the West, choose to return home for personal or professional reasons – be it the pull of family, the attraction of India’s growing market or a desire to contribute to their homeland. For example, in the past few years, senior executives from Silicon Valley have moved to Bangalore to lead Indian tech firms or venture funds.

Certain government initiatives, like the ones mentioned (Ramanujan fellowships, etc.), have convinced expatriate researchers to come back. While these returnees are still a trickle compared to the outflow, they have outsized impact by bringing global expertise to India’s institutions. Each such case also serves as a symbol of possibilities, showing that India can be a place where world-class careers are possible.

In essence, India’s aim is to strike a balance – to maintain a healthy circulation of talent. As one commentator framed it, the goal should be not to completely halt brain drain (which is neither feasible nor desirable in an open world), but to transform it into brain circulation where the Indian “brain network” spans continents but remains connected to India. With strategic engagement, the vast Indian diaspora can be India’s “brain reserve,” contributing to national development through remittances, investments, knowledge exchange, and even return migration. Or as a pithy saying goes, if China has built physical infrastructure across the world, India has built influence through its people. Harnessing that influence is key to turning the brain drain narrative into one of brain gain.

Toward brain gain

Reversing India’s brain drain is a complex challenge – akin to “navigating a labyrinth,” as one policy forum described it. There is no single magic bullet; it requires coordinated improvements across India’s educational, economic and governance landscape. The analysis above suggests a dual focus strategy. In the short to medium term, India must continue enhancing domestic opportunities for excellence: better universities, more R&D funding, thriving industries and liveable cities.

When talented Indians see that they can fulfill their aspirations at home nearly as well as abroad, the incentive to leave will naturally diminish. Initial signs are encouraging – India’s rising economy and vibrant tech sector are already persuading some to stay, and even luring back a few who left. If sustained, investments in research, innovation and education will gradually make India a global knowledge hub in its own right, not just a supplier of talent to hubs elsewhere.

Equally important is the long-term groundwork of human capital development. This means fixing the leaky pipes at the source: providing quality schooling and mentorship at the grassroots so that all Indians with ability can rise. By broadening and diversifying the talent pipeline, India ensures that one person’s emigration is not a catastrophic loss because many others are ready to step up. And those who do rise from humble roots might be more inclined to drive change in their communities, creating a virtuous cycle of development. Over time, a more inclusive and robust domestic talent pool will reduce the desperation or necessity that often underlies brain drain. It will also produce leaders who are socially rooted and perhaps less inclined to permanently relocate, preferring instead to improve conditions in India. As this happens, the narrative shifts “from brain drain to brain gain” – with India not only sending out talent, but increasingly attracting talent and capital back.

Finally, embracing the diaspora as partners is crucial. Rather than lamenting those who left, India is learning to leverage their success. The vision of Viksit Bharat (Developed India) 2047, by the time India reaches 100 years of independence, explicitly counts on diaspora collaboration and returnees to boost India’s leap into a developed, innovation-driven economy. This is a pragmatic and modern outlook: in a globalised world, migration can be a win-win if managed well.

Migrants gain skills and income abroad, and with the right incentives and attachments, their homeland can benefit through remittances, investments and knowledge transfer. The key is keeping the connections alive. India’s policies are gradually moving in that direction – from easier OCI (Overseas Citizen of India) cards to involving diaspora experts in advisory roles. If India succeeds, it will exemplify what some scholars term not a brain drain but a “brain circulation” system, where human capital flows out but also circulates back in new forms.

In conclusion, India’s brain drain challenge is real and pressing, but it is not insurmountable. The country’s vast population means it can continue to supply global talent, but with wise policy it can also increasingly retain talent and welcome it back. The road to brain gain runs through strengthening institutions at home and building bridges abroad. By tackling educational inequities, improving research ecosystems, incentivising returns and leveraging its diaspora, India can turn the tide. The transformation will not happen overnight – it’s a generational endeavour – but the stakes are high. A India that keeps its best minds (or welcomes them back after they win laurels abroad) will be in a far stronger position to innovate, grow economically, and solve its development challenges.

The brain drain, in other words, can be converted into a brain trust. As India marches towards great-power status, retaining its human capital will be as vital as any infrastructure or economic reform. The coming years will test whether India can indeed channel its famed talent pipeline inward for its own advancement, fulfilling the promise of “brain gain” after decades of brain drain.