When the pandemic brought India’s informal economy to a standstill, Yashoda’s household income collapsed almost overnight. Her husband, a cab driver in Bengaluru, lost his job. Rent, school fees and groceries did not pause in solidarity. Faced with precarity, Yashoda did what millions of Indian women have always done in times of crisis — she adapted.

Through Smile Foundation’s Entrepreneur Development Training Programme, she acquired business skills and mobilised other women in her neighbourhood who were similarly affected. Together they launched Kadamba Naturals, a handmade organic cosmetics enterprise producing lip balm, kajal, bathing salt and herbal powders. What began as a coping mechanism has evolved into an enterprise with expansion plans and a collective vision of financial independence.

Yashoda’s story is both inspiring and unsettling. Inspiring because it reflects resilience. Unsettling because it exposes a systemic gap in India’s entrepreneurship narrative.

India today ranks among the world’s fastest-growing startup ecosystems, with over 110,000 DPIIT-recognised startups and a digital economy projected to reach $1 trillion by 2030. But women remain significantly underrepresented in this story. According to NITI Aayog and industry estimates, women account for roughly 14–18% of entrepreneurs in India, and even fewer operate within the formal, scalable sector. Access to institutional funding remains starkly unequal — global data suggests women-led startups receive less than 3% of venture capital funding, a pattern mirrored in India.

But the constraint is not only capital.

What’s Failing Beyond Funding?

For years, policy discourse has centred on the funding gap. Indeed, access to credit remains constrained by collateral requirements, documentation burdens and implicit bias. However, capital flows toward visibility, compliance, scalability and measurable performance. And those are increasingly digital metrics.

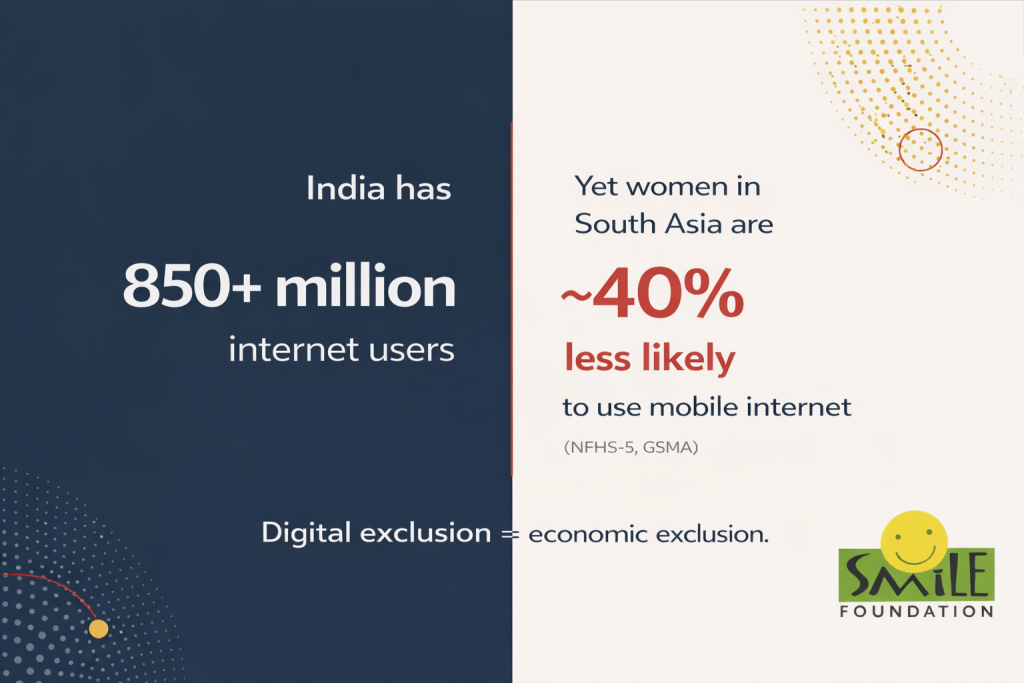

India’s digital transformation has been profound. Over 850 million internet users, the rapid adoption of UPI with over 10 billion transactions monthly, Aadhaar-enabled verification systems and expanding e-commerce platforms have reshaped economic participation. Yet the gender digital divide persists. According to NFHS-5, women are significantly less likely than men to use the internet. GSMA estimates that women in South Asia are around 40% less likely to use mobile internet than men.

This gap shapes entrepreneurial opportunity.

Government schemes offer credit lines and subsidies. But applying requires uploading documents, navigating portals, undergoing digital verification and maintaining transaction histories. For many first-generation women entrepreneurs, the barrier is not ambition — it is digital fluency.

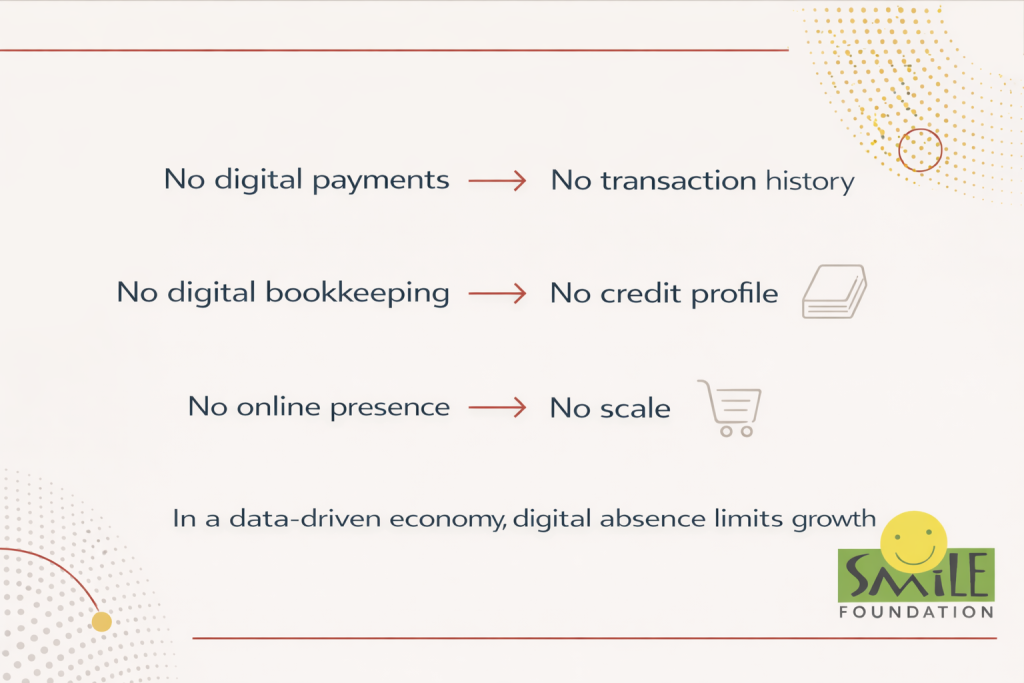

Even after securing credit, growth demands digital marketing, online listings, customer engagement tools and digital bookkeeping. Without these, businesses remain hyperlocal and low-margin. In an economy increasingly governed by data trails and compliance frameworks, absence from the digital ecosystem translates into structural exclusion.

Mobility constraints, unpaid caregiving responsibilities and gendered norms further restrict risk-taking and time investment. Women are often channelled into low-investment sectors like tailoring, food processing, home-based production, with limited scale. The digital layer could unlock growth. Without it, stagnation is likely.

Why Digital Is the Structural Lever for Women Entrepreneurship Story

Accepting digital payments creates transaction histories. Listing products online expands geographic reach. Maintaining digital inventory improves supply chain reliability. Digital bookkeeping builds creditworthiness. These are not technical upgrades; they are gateways into formal finance and larger markets.

India’s policy architecture, from ONDC to Account Aggregator frameworks, is building a data-driven economy. Entrepreneurs without digital records are invisible to these systems.

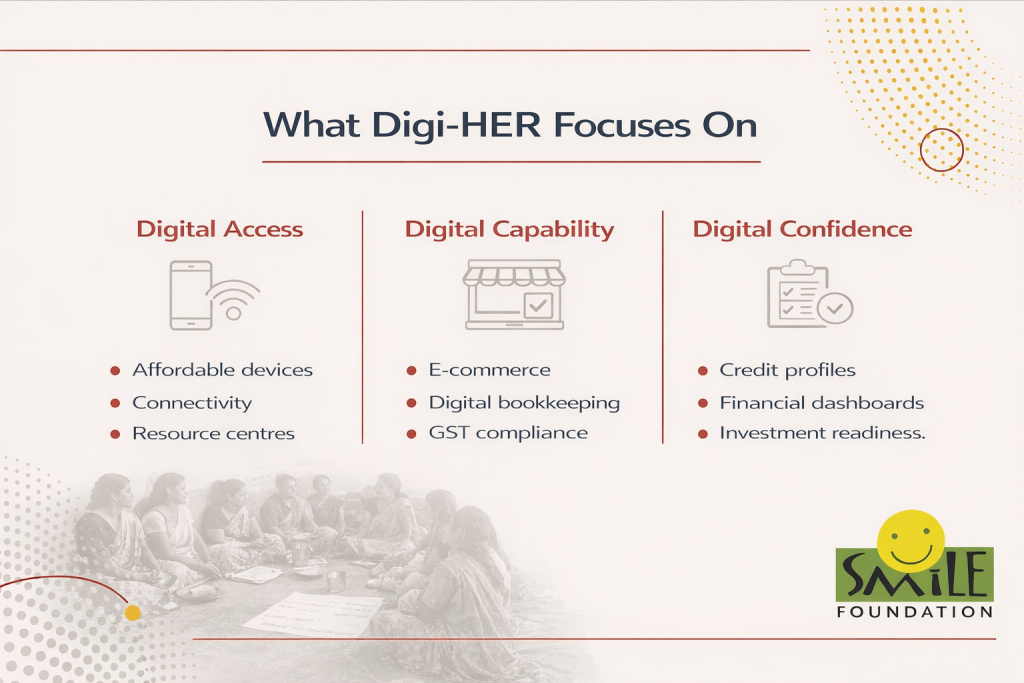

Digi-HER responds to this structural reality.

1. Digital Access

Bridging device and connectivity gaps is foundational. Affordable smartphones, reliable internet, shared digital resource centres and mobile-first training content reduce entry barriers. In underserved districts, community-based digital hubs can serve as entry points into formal commerce.

2. Digital Capability

Skills training must go beyond theoretical literacy. Women entrepreneurs need applied, contextual learning — how to list products on e-commerce platforms, use WhatsApp Business, maintain GST-compliant records, analyse sales dashboards and manage online payments. Flexible, modular formats that accommodate caregiving schedules are critical.

3. Digital Confidence Linked to Capital

Digital fluency must connect to financial mobility. Transaction histories enable credit scoring. Financial dashboards build negotiation power. Digital pitch decks increase investor readiness. When women control their financial data, they strengthen their bargaining position within both markets and households.

Lessons from the Ground for Women Entrepreneurship Story

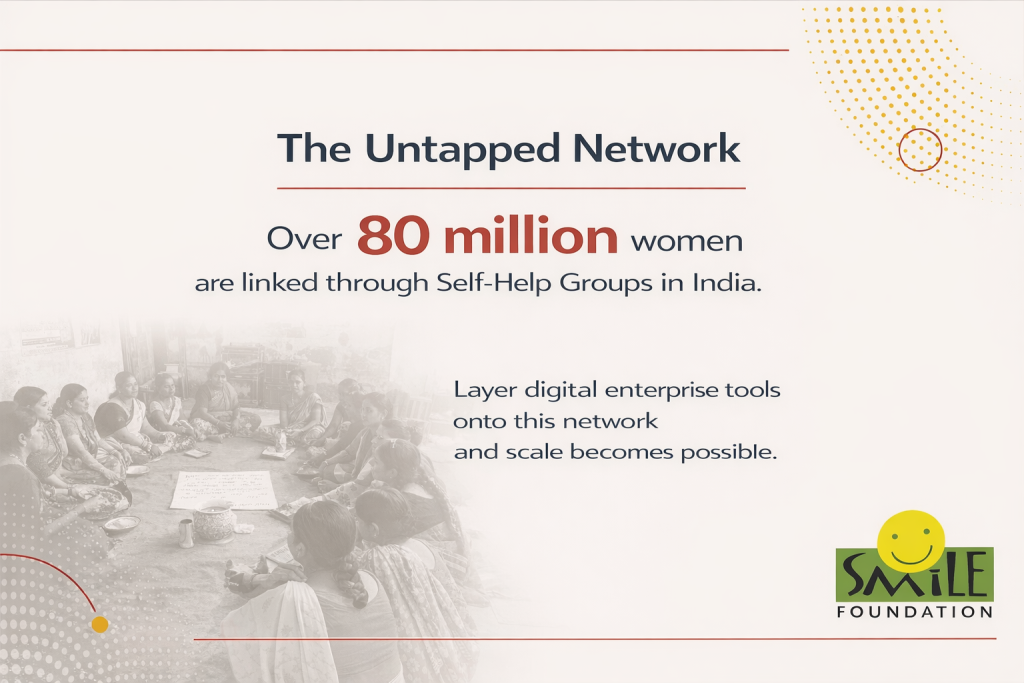

Self-Help Groups and collective enterprise models continue to demonstrate scale potential. When tailoring and food-processing groups combine skill development with digital market linkage, they move from neighbourhood sales to district-level contracts. When financial literacy is paired with digital tools, women gain control over income and savings.

Recent government data shows over 80 million women linked through SHGs under the National Rural Livelihoods Mission. The opportunity is to layer digital enterprise capability onto this existing social capital network.

The evidence is clear: credit alone does not transform businesses. Digital integration, market linkage and institutional support must operate together.

A Broader Economic Imperative

India cannot claim inclusive growth while half its entrepreneurial capacity remains digitally constrained. The IMF estimates that closing gender gaps in labour force participation could raise India’s GDP significantly. Yet entrepreneurship — a critical pathway to economic participation — remains unevenly distributed.

As India accelerates toward a $5 trillion economy, the question is not whether women can build enterprises. They already are. The question is whether the systems around them will evolve fast enough to recognise, finance and scale their efforts.

Digital empowerment is not an add-on to women’s entrepreneurship. It is its operating system.

Encouragingly, initiatives are beginning to reflect this shift. Smile Foundation’s Swabhiman programme integrates women entrepreneurship development with digital and financial capability building, alongside health and hygiene interventions. But systemic change will require alignment between public digital infrastructure, private platforms, financial institutions and grassroots training ecosystems.

If India’s digital public goods revolution has shown anything, it is that infrastructure can leapfrog barriers. The next leap must ensure that women entrepreneurs are not merely participants in this digital economy but architects of it.

Only then will stories like Yashoda’s move from resilience narratives to scalable economic transformation.