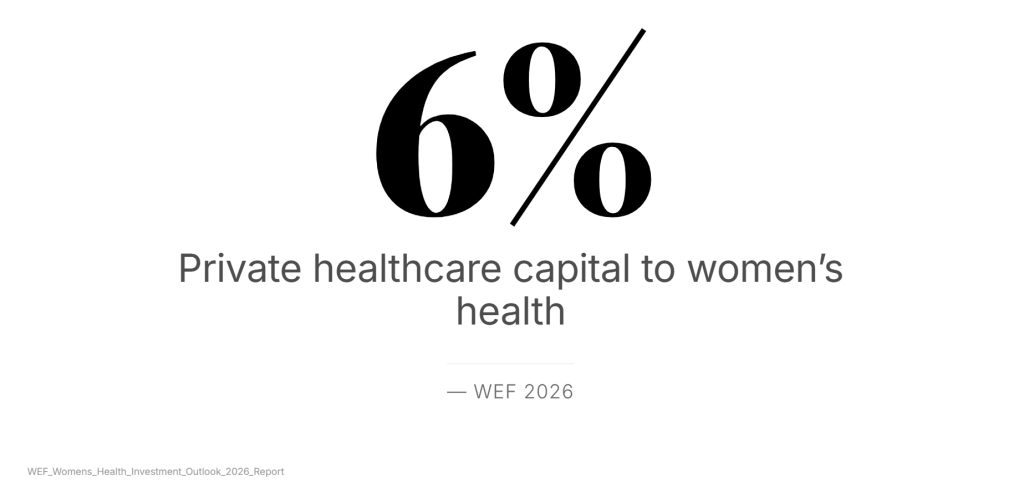

Globally, women’s health receives only 6% of private healthcare investment . Much of that funding is concentrated in reproductive health, maternal care and women’s cancers. But women’s health extends far beyond childbirth. In India, national data reveals how structural neglect translates into measurable risk.

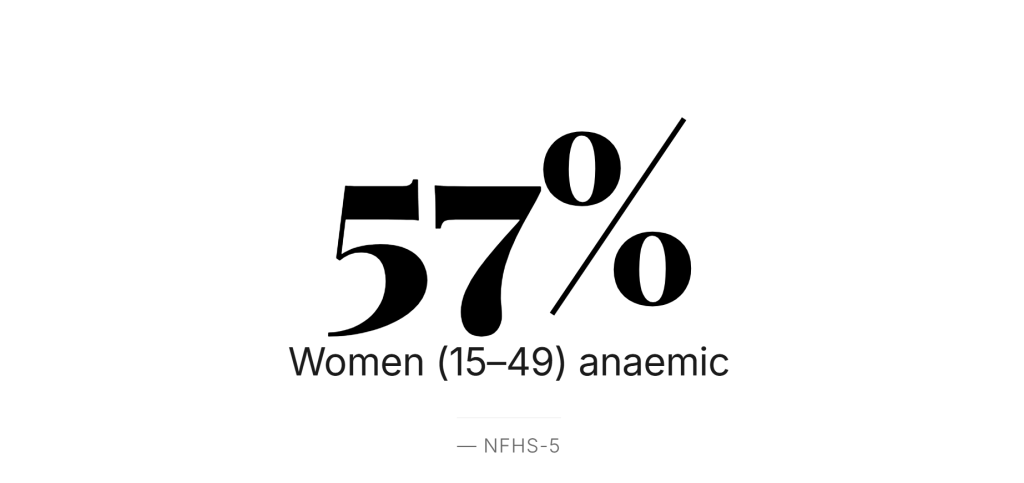

Anaemia: The Silent Normal

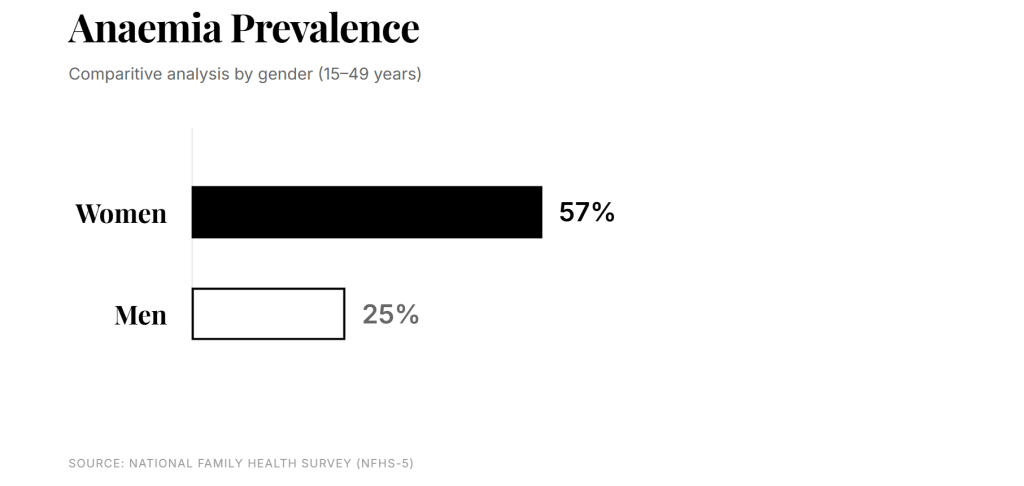

The National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5, 2019–21) reports that 57% of women aged 15–49 in India are anaemic. Among adolescent girls (15–19 years), the rate exceeds 59%.

Anaemia is not a minor condition. It affects cognitive functioning, work capacity, pregnancy outcomes and long-term cardiovascular health. Yet in many communities, it is so common that it is perceived as inevitable.

The cost is not only medical. It is educational and economic. Fatigue impairs concentration. Repeated illness disrupts schooling. Maternal anaemia increases the likelihood of low birth weight, perpetuating intergenerational disadvantage.

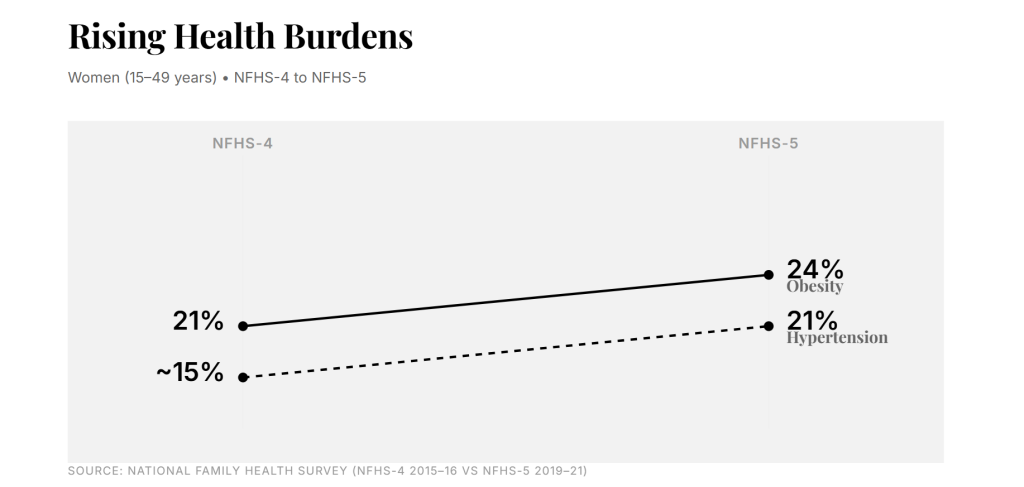

The Rising Burden of Non-Communicable Diseases

While maternal mortality has declined significantly over the past two decades, India now faces a growing epidemic of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) among women.

According to NFHS-5:

- 21% of women aged 15–49 are overweight or obese, up sharply from NFHS-4.

- Nearly 11% of women have high blood sugar levels, indicating rising diabetes risk.

- Hypertension prevalence among women has steadily increased, particularly in urban and peri-urban regions.

Cardiovascular disease is now one of the leading causes of death among women in India. But awareness remains low, and symptoms are frequently misinterpreted.

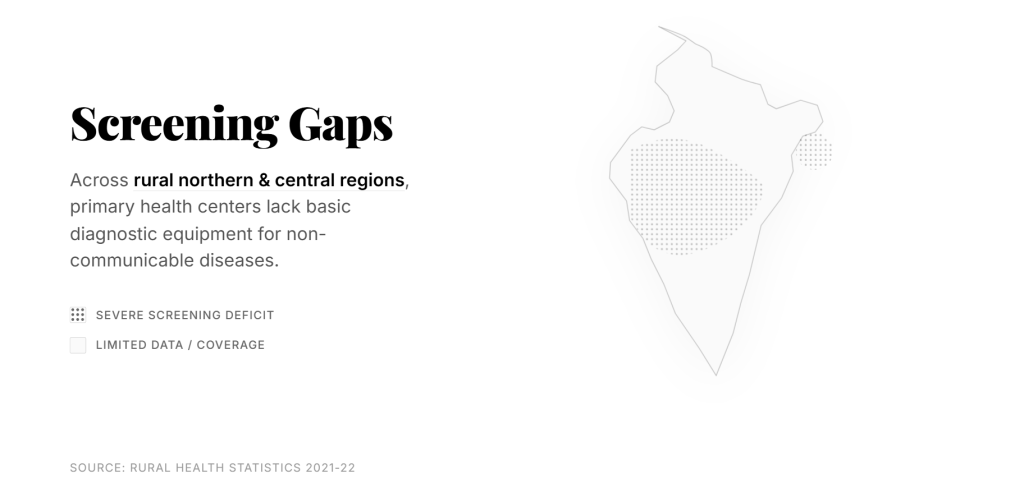

Under the National Programme for Prevention and Control of Cancer, Diabetes, Cardiovascular Diseases and Stroke (NPCDCS), the National Health Mission has expanded screening initiatives at the primary care level. Millions of individuals have been screened for hypertension and diabetes. However, screening coverage remains uneven, particularly in underserved rural and informal urban settlements.

The gap lies not only in availability but in continuity. Screening must translate into sustained management, follow-up, and awareness — especially for women who often prioritise family health over their own.

Maternal Health Gains and Persistent Gaps

India has made measurable progress in maternal health. According to the Sample Registration System (SRS), the Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) declined to 97 per 100,000 live births (2018–20). Institutional deliveries now exceed 88% nationally (NFHS-5).

Yet improved survival does not equate to comprehensive health.

Postnatal care, mental health screening and long-term metabolic monitoring remain limited. Postpartum depression remains underdiagnosed. Women with gestational diabetes often receive little follow-up, despite increased lifetime risk of Type 2 diabetes.

The policy architecture has strengthened. The life-course support system has not kept pace.

Mental Health: Data and Silence

National surveys indicate that women are more likely than men to report symptoms of anxiety and depression. However, mental health service utilisation remains low due to stigma, limited availability and cultural barriers.

In low-resource communities, psychosocial stress is compounded by economic precarity, domestic responsibilities and restricted mobility. Yet mental health remains marginal in women’s health conversations.

This silence has consequences — for parenting, productivity and long-term wellbeing.

Adolescent Health: The Overlooked Window

The adolescent period is a critical intervention point.

NFHS-5 shows persistent high anaemia levels among adolescent girls. Early marriage, though declining, continues in several states. Nutrition gaps during adolescence affect not only immediate cognitive development but also maternal health later in life.

Programmes under the National Health Mission and POSHAN Abhiyaan aim to address these deficits. But effective change requires sustained community engagement, accurate health literacy and access to screening — not only policy announcements.

Environmental and Socioeconomic Risk

Health burdens are not evenly distributed.

Lower-income households are more likely to reside in areas with poor air quality, limited sanitation and constrained healthcare access. Women in such environments face compounded exposure — indoor air pollution from cooking fuels, inadequate nutrition and limited preventive care.

These overlapping risks magnify vulnerability.

Community-Level Interventions: Bridging Immediate Gaps for Underinvestment in Women’s Health

In underserved communities, non-governmental initiatives often function as the first line of access.

Mobile healthcare units — such as those operated under Smile Foundation’s Smile on Wheels programme — conduct:

- Blood pressure and blood sugar screening

- Anaemia detection

- Antenatal check-ups

- Nutrition counselling

- Referral support

School-based programmes address menstrual hygiene, adolescent nutrition and early health awareness. Community sessions create safe spaces to discuss symptoms that might otherwise remain hidden.

These interventions do not replace systemic reform. But they address immediate diagnostic gaps and strengthen health literacy.

The Economic Argument

The World Economic Forum’s 2026 analysis argues that women’s health is not only a social imperative but an economic one . Healthier women participate more consistently in the workforce, reduce healthcare shocks and support stronger educational outcomes for children.

In India, where women’s labour force participation remains comparatively low, health barriers represent a structural constraint.

Preventive investment yields compound returns.

The Structural Question

India’s public health infrastructure has expanded screening and institutional delivery rates. Yet preventive, life-cycle-based women’s healthcare remains fragmented.

Underinvestment — globally and nationally — shapes what is prioritised. When funding and innovation focus narrowly on maternal care, broader metabolic, cardiovascular and mental health conditions receive less systematic attention.

The result is not absence of care. It is partial care.

Reframing Women’s Health

Women’s health is not confined to reproductive years. It spans adolescence, early adulthood, mid-life metabolic risk and ageing-related conditions.

If anaemia affects more than half of reproductive-age women, if obesity and hypertension are rising, and if mental health remains marginalised, then the issue is not niche.

It is foundational.

The invisible epidemic is not defined by a single disease. It is defined by cumulative neglect — of screening, awareness, and preventive continuity.

Correcting this imbalance requires:

- Stronger primary healthcare integration

- Gender-sensitive NCD screening protocols

- Mental health inclusion

- Community-based health literacy

- Public-private collaboration

Women’s health is infrastructure. It underpins education, economic stability, and intergenerational resilience.

The data already exists. The question is whether investment and implementation will follow.