India has long measured maternal health in clinical terms — haemoglobin counts, institutional delivery rates, antenatal check-ups, nutritional supplements. But buried beneath these familiar metrics is another crisis, quieter and harder to quantify: the mental health of mothers. It is a crisis that rarely makes it into government dashboards or political speeches, but it is one that shapes both the health of women and the futures of the children they bring into the world.

In conversations with frontline workers across rural Rajasthan, urban Maharashtra and tea estates in Assam, one pattern repeats itself: women who are overwhelmed, anxious, depressed — but almost entirely unseen by the system. A young mother in Jaipur, cradling her newborn, quietly admits she hasn’t slept in days and sometimes feels frightened of being alone with her baby. A tribal woman in Odisha says the hardest part of pregnancy is “thinking too much,” but she never told the ASHA worker because “everyone has problems.” A migrant worker in Mumbai breaks down because she is still grieving the loss of her first child, even as she prepares to deliver her second.

These women are not outliers. They are the face of a public health challenge that remains largely invisible: one in five women in India experiences mental health difficulties during pregnancy or postpartum, according to emerging evidence. Yet mental health is still treated as a secondary concern — an optional extra in a system that is already overburdened.

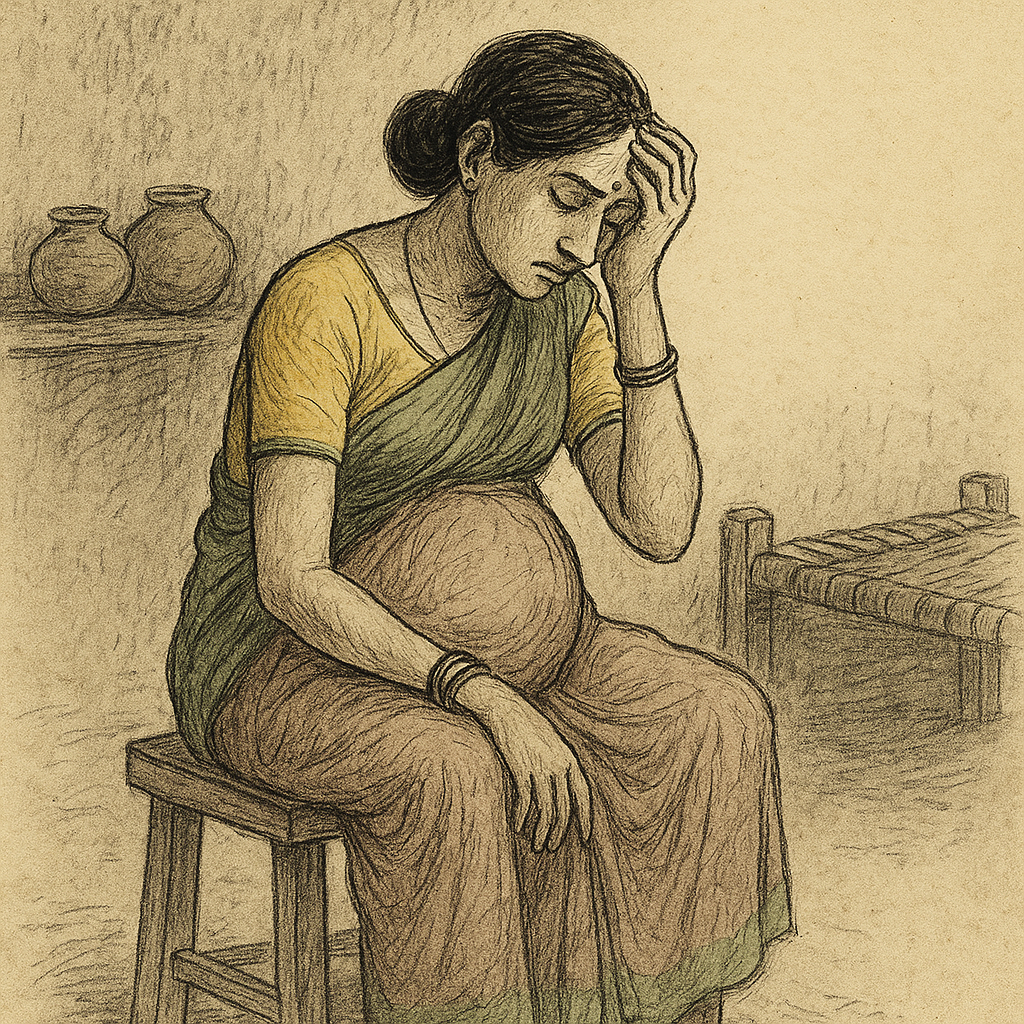

The emotional weight of pregnancy

Pregnancy is often portrayed culturally as a time of joy, anticipation, and celebration. But for many women, especially those living in poverty, navigating unstable relationships, or lacking support, it is also a period of profound vulnerability.

Antenatal depression and anxiety do not occur in isolation. They are shaped by the social conditions surrounding women: food insecurity, domestic violence, long working hours, inadequate housing and the sheer physical labour involved in surviving day to day. For millions, pregnancy unfolds against the backdrop of smoky kitchens, demanding jobs and constant financial precarity.

When a woman is expected to cook for a family of eight over a chulha, or carry bricks on a construction site through her third trimester, it is unsurprising that her mental resilience begins to fray. Yet the system is rarely designed to recognise this emotional toll. The assumption is simple and outdated: if a woman is physically healthy, she must be well.

The silence around mental healthcare in maternal health

In a country where conversations around mental health still carry stigma, maternal mental health occupies an even more silenced corner. Many women do not have the vocabulary to describe what they are feeling. Words like “stress,” “worry,” and “tension” are used as catch-alls that mask more serious symptoms.

Family members often misinterpret mood changes as weakness or ingratitude. A woman who expresses sadness after childbirth is told she is “overthinking,” while one who feels anxious is encouraged to “be strong for the baby.” Depression becomes reframed as a lack of discipline or devotion. This cultural framing traps women in isolation.

Healthcare workers, too, are rarely trained to recognise perinatal mental health concerns. In overburdened clinics, the priority is blood pressure, weight and foetal growth. Mental health, if addressed at all, is reduced to the occasional question: “Do you feel fine?” Most women simply nod.

The consequences ripple across generations

Maternal mental health is not merely a private emotional matter — it has profound implications for public health. Research globally and increasingly in India shows that untreated maternal depression can affect foetal growth, increase the risk of preterm birth and influence early childhood development.

After childbirth, maternal mental health continues to be a powerful predictor of infant outcomes. A mother who is depressed may struggle with breastfeeding, bonding and maintaining consistent infant care. Children born to mothers with untreated depression are more likely to experience developmental delays, lower school readiness and behavioural challenges.

Mental health during pregnancy and postpartum is therefore not a separate silo; it is deeply interwoven with the long-term health, education and social mobility of the next generation. The wellbeing of women is the wellbeing of children — the chain is unbreakable.

A gap between policy and reality

India has made impressive strides in maternal health over the last two decades. Institutional deliveries have risen sharply. Maternal mortality has fallen. But mental health still lies outside the purview of most national programmes.

While the National Mental Health Programme acknowledges perinatal conditions, frontline implementation remains weak. In many states, mental-health positions remain vacant. Primary care physicians rarely receive systematic training on identifying perinatal depression. Screening tools exist, but they are seldom used.

Even where guidelines emphasise women’s mental wellbeing, their execution is hobbled by lack of resources, limited digital record-keeping and competing priorities. A single ASHA worker covering hundreds of households may not have the time or training to probe mental health concerns.

The gap is not due to lack of evidence, but lack of urgency.

What better maternal healthcare could look like

A maternal health system that genuinely integrates mental health would not be radically expensive or administratively complex. It would require three shifts: recognition, training, and community support.

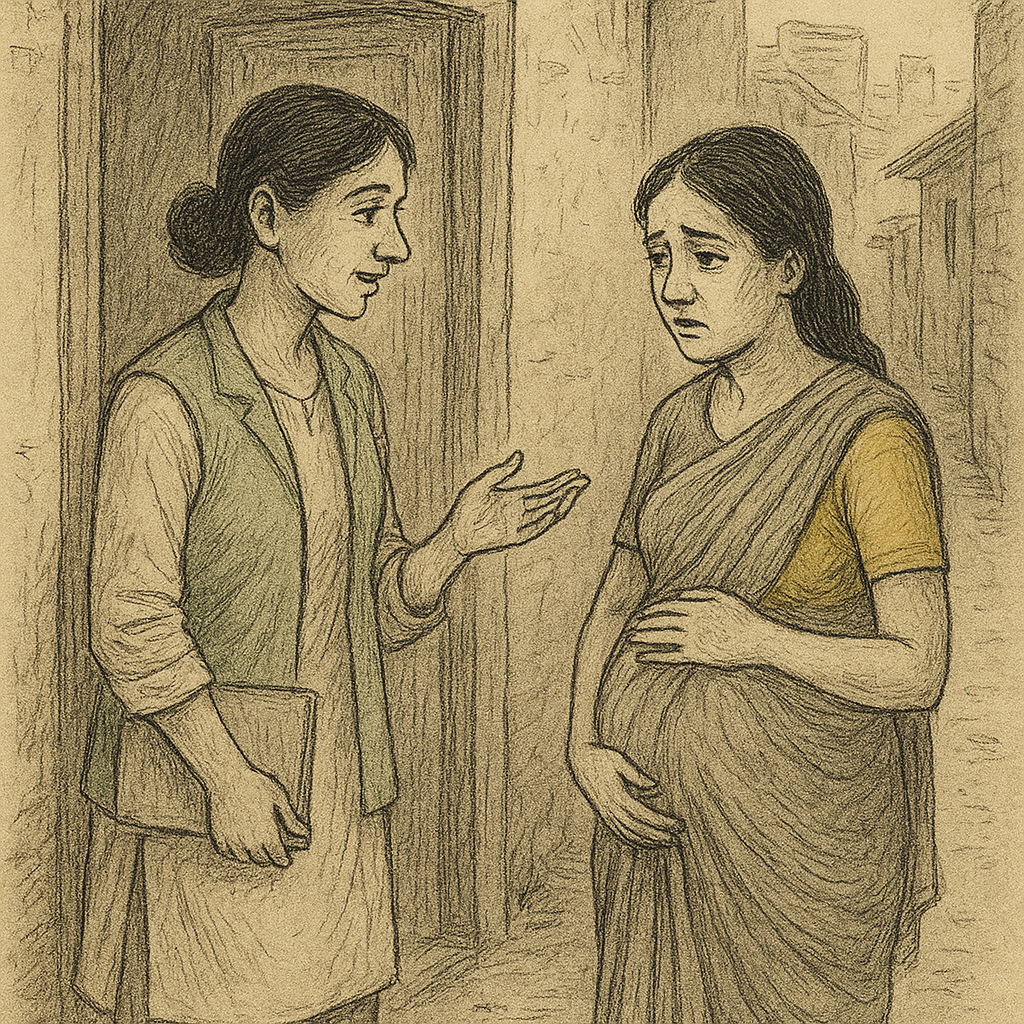

First, recognition: Healthcare providers must be encouraged to see mental health as a core part of antenatal and postnatal care, not a luxury. A simple screening question asked earnestly can change the trajectory of a woman’s care.

Second, training: ASHA workers, ANMs, and primary care physicians are the backbone of India’s maternal health system. Equipping them to detect red flags — persistent sadness, withdrawal, fear or loss of appetite — could dramatically improve early intervention.

Third, community support: Women who are supported by families, neighbours and social networks are more resilient. Programmes that work with husbands, mothers-in-law and community leaders to recognise emotional distress can help shift the culture that normalises women’s suffering.

Examples from states such as Telangana — where pilot initiatives have trained primary care providers in perinatal mental health — offer a glimpse of what a strengthened system can achieve.

The emotional burden of care

What often goes unspoken is the emotional labour women are expected to perform immediately after childbirth — hosting visitors, cooking, cleaning, caring for older children — at a time when their bodies and minds are still recovering. The expectation that women must cope without complaint adds to their distress.

Postpartum depression is not a sign of failure. It is a sign of the impossible burdens mothers face.

A call to take women seriously

Maternal mental health deserves mainstream attention not because it is a “soft” issue, but because it is a foundational one. Women cannot be expected to carry the weight of pregnancy, labour, childcare and household responsibilities while also navigating emotional pain in silence.

If India wants to ensure healthy mothers and thriving children, it must start by taking seriously something it has long ignored: the inner lives of women.

Mental health is not a footnote to maternal healthcare. It is the hinge on which the wellbeing of families — and future generations — turns.

A future where women feel seen

Imagine a maternal healthcare system where a woman can say, “I’m struggling,” and know she will be heard. Where her emotional health is checked as routinely as her blood pressure. Where support doesn’t depend on luck or geography, but on a system that values her dignity and humanity.

Integrating mental health into maternal healthcare is a recognition that women are whole people, not vessels for childbirth. It acknowledges that the path to healthier families begins by caring for the minds of mothers.

India has transformed maternal health before. It can do so again — this time, by ensuring that women’s emotional wellbeing is not the missing piece.

Where hope is beginning to take shape

Across the country, small but meaningful attempts are already showing what is possible. Organisations working at the community level are creating shifts — often long before policies catch up.

Smile Foundation, for instance, has begun integrating mental health conversations into its maternal and child healthcare programmes. Our community health workers, trusted faces in some of the most underserved neighbourhoods, are being trained to recognise early signs of distress, counsel women and link them to care. In places where women rarely speak about what they feel, these conversations are offering a lifeline.

It is not a grand reform. It is not loudly advertised. But it is changing something essential: women no longer feel invisible.

And that is the starting point for any real transformation.

If India can scale efforts like these — pairing clinical care with emotional support and giving women the space to be honest about their struggles — maternal health will look very different in the years ahead. Healthier mothers, stronger families and children who begin life with the stability and security they deserve.

Maternal mental health is not a side note. It is the story. And the sooner we treat it that way, the more hopeful the future becomes.