In a small maternity ward in rural India, a young mother cradles her newborn with a mixture of awe and fear. Her baby’s heartbeat, fragile and insistent, is reminds one of both possibility and risk. Across the country, thousands of parents wake up to this same fragile hope. But whether that hope survives the first year of life often depends not on parental devotion, but on where the child is born.

India has made undeniable progress in reducing infant deaths. Kerala now records just 5 deaths per 1,000 live births, one of the lowest rates in the country. Nationally, infant mortality has dropped to 25 per 1,000—the lowest in India’s history, and a milestone that should not be understated. It is a sign that improvement is possible, that lives can indeed be saved. But it is also a reminder of how deeply unequal survival remains across the subcontinent. For all the headlines about progress, the truth behind the numbers is that far too many children still die from causes that should, by now, be consigned to history.

A Mirror of Inequality

Infant mortality is not evenly distributed across India’s vast landscape. It mirrors the country’s most stubborn inequities—geographical, economic, social. The emotional toll is immeasurable: the mother who watches her child slip away because the nearest clinic lacks oxygen; the father who cannot afford transport to a district hospital; the family that buries a newborn because the local health worker never arrived.

In rural communities, these tragedies often unfold amid isolation, shame, and entrenched cultural expectations. Women are frequently blamed—quietly, pointedly—for their child’s death, accused of neglect or misfortune. Such reactions only deepen the trauma, adding emotional injury to physical loss. But the real causes lie elsewhere: in the lack of nutrition for expectant mothers, inadequate antenatal care, unsafe birthing environments, and the absence of timely medical support. Infant mortality, perhaps more than any other health indicator, reveals the geography of opportunity, and of neglect.

Why Newborns Die: The Preventable Causes

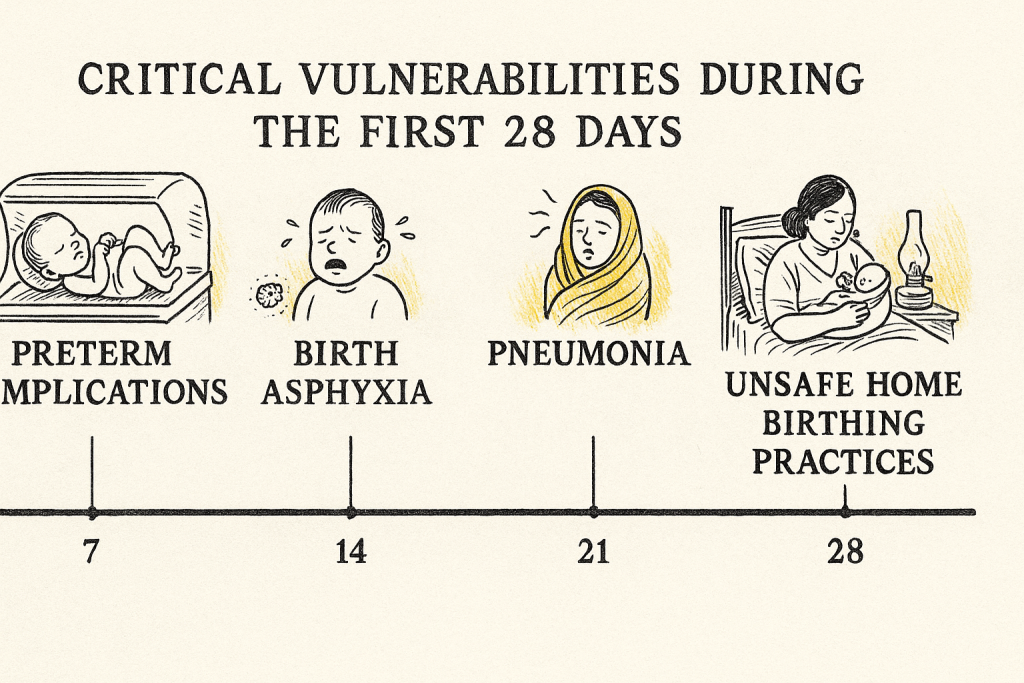

Across India, nearly half of all deaths among children under five occur within the first 28 days—the neonatal period. The causes are well understood. Complications of preterm birth. Birth asphyxia. Infections like sepsis and pneumonia. These are not mysterious ailments; they are predictable, largely preventable conditions that require functioning health systems, supportive nutrition programmes and skilled care during childbirth.

For infants aged one to twelve months, the threats shift slightly: diarrhoea, malaria, malnutrition. Congenital disorders also claim lives throughout the first year. But the underlying story remains the same: too many children are born into circumstances that drastically limit their chances of surviving into toddlerhood.

Poor maternal health plays an outsize role. Anaemia, still stubbornly prevalent among Indian women, weakens both mother and child. Malnutrition during pregnancy increases the risk of low birth weight and premature delivery. These vulnerabilities cascade, making newborns susceptible to infections and complications that stronger, healthier infants might withstand.

Hidden Costs: Social, Emotional, Economic

The death of an infant reverberates far beyond the family’s grief. Siblings grow up under the shadow of loss. Communities lose trust in health systems that they perceive as indifferent or unreliable. Overstretched hospitals must redirect scarce resources toward emergency interventions that could have been prevented.

On a national scale, these losses translate into diminished human capital. Every infant death represents a future foreclosed—a worker never trained, a student never enrolled, a life never lived. Economic progress is, at its core, the story of human potential. When infants die, that potential is erased before it can even begin.

When Culture Undermines Care

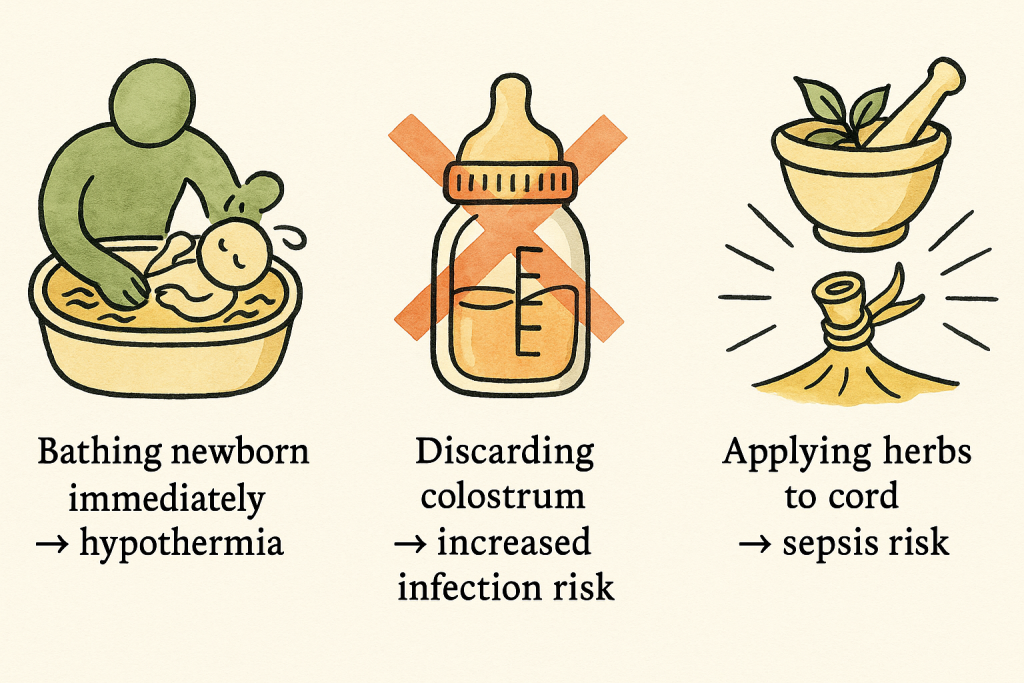

India’s cultural landscape is rich and diverse, but certain traditional practices continue to undermine newborn health. Essential Newborn Care (ENC)—the gold standard for safe infant care—recommends keeping babies warm, avoiding early bathing, ensuring hygienic cord care and breastfeeding within the first hour. Yet in many communities, babies are bathed immediately after birth, exposing them to hypothermia. Herbal substances are placed on the umbilical cord, inviting infection. Colostrum, the thick, antibody-rich first milk that protects infants from disease, is sometimes discarded due to misconceptions about impurity.

Gender norms deepen these risks. In many regions, the birth of a girl can bring disappointment, even resentment. This bias manifests in tragic ways: daughters receive less nourishing food, are taken to health clinics later than boys, or are simply neglected. The recent case in Rajasthan’s Sikar district, where a father allegedly killed his infant twin daughters, serves as a grim reminder that cultural attitudes remain deadly. Addressing these realities requires more than medical interventions; it requires confronting the social beliefs that shape daily decisions about newborn care.

Strengthening Mothers, Strengthening Newborns

The wellbeing of a newborn is inseparable from the wellbeing of the mother. A healthy pregnancy sets the stage for a healthy start to life, but that requires access to antenatal care, nutritious food and safe delivery services.

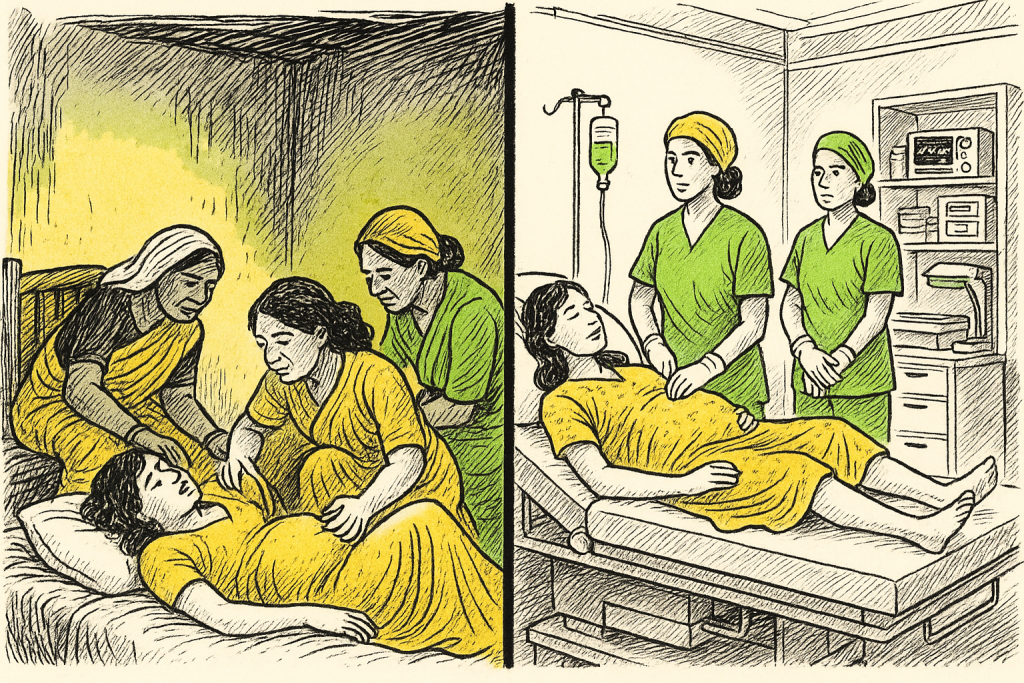

Government initiatives like the Pradhan Mantri Surakshit Matritva Abhiyan (PMSMA) and SUMAN have expanded access to antenatal check-ups and improved conditions for childbirth. Investments in midwife training, essential delivery kits and well-equipped birth centres are crucial steps toward ensuring dignified deliveries. But coverage remains uneven, and too many rural communities still rely on under-resourced facilities or unskilled birth attendants.

Mobile medical units, simple vans staffed with nurses and doctors, offer a lifeline in remote areas, stitching together the vast distances that often separate families from healthcare. When functioning well, they bring antenatal check-ups, vaccinations, counselling and emergency support directly to rural hamlets that are otherwise cut off.

Empowering adolescent girls is equally critical. Ensuring their nutritional health, providing menstrual hygiene resources and offering reproductive health education strengthens future mothers long before pregnancy begins.

The Cultural and Policy Gap

Despite ongoing efforts, the gap between policy goals and lived reality is often wide. Many frontline health workers shoulder impossible caseloads. Clinics in remote districts may have electricity only intermittently. Ambulances, when they arrive at all, may come too late. Public health messages often fail to penetrate local belief systems. India’s successes, like Kerala’s low mortality rate, demonstrate what is possible when governance, healthcare and public awareness align. But replicating those successes nationwide requires sustained political will, well-funded health systems and deep engagement with women and communities who navigate these risks daily.

Why This Moment Matters

India stands at a demographic crossroads. Its aspirations, to become a major global economy, to harness its youth bulge, to strengthen its workforce, will falter if it cannot secure the survival of its youngest citizens. Infant mortality is not merely a health statistic; it is a measure of whether a nation is honouring its most fundamental obligation: to protect life at its most vulnerable.

The sobering truth is that many infant deaths are not inevitable tragedies but preventable outcomes. They reveal where systems have failed, where knowledge has not reached, where nutrition is inadequate and where women lack autonomy over their own health.

A Future Worth Building

Among the civil society organisations confronting these challenges, Smile Foundation stands out for its sustained work in maternal and child health. Through programmes like Swabhiman and Smile on Wheels, the foundation delivers essential healthcare to underserved communities, promotes institutional deliveries, supports maternal nutrition and raises awareness about breastfeeding and newborn care. By bringing health services directly into communities through mobile clinics, trained volunteers and behaviour change initiatives, it helps ensure that more children survive the precarious first months of life.

These models demonstrate what is possible when systems meet people where they are, when services take into account cultural contexts, and when mothers are treated not as passive recipients but as central partners in their health journey.

The Promise in Every Heartbeat

A newborn’s first cry is not just a biological reflex; it is a declaration of possibility. Every tiny heartbeat holds the promise of a future, an education, a livelihood, a life lived fully. For India to secure that promise, it must transform not only its health systems, but also its social structures, cultural norms and political priorities.

When we care for mothers, educate girls, strengthen health systems and confront harmful practices, we do more than reduce mortality. We affirm a simple but profound belief: every child deserves the chance to grow, to thrive and to shape the future of the nation.

That future begins in the first year of life. And its protection is one of the most urgent responsibilities we have.