India faces a persistent shortage of qualified teachers, especially in primary and upper-primary schools. Recent government analyses highlight this crisis – a parliamentary committee reported “around 10 lakh vacancies of teachers in SSA-funded schools… and around 7.5 lakh vacancies at the elementary and primary levels”. Times of India notes that some states (e.g. Bihar, Karnataka, Rajasthan) have tens of thousands of unfilled posts and hundreds of schools operating with only one or two teachers. These gaps push actual pupil–teacher ratios far above the NEP 2020 guideline of 30:1 (25:1 in disadvantaged areas). For example, Bihar reports over 14,000 schools exceeding a 40:1 ratio and national data show many schools disobeying PTR norms.

The shortage is acute in rural and remote areas. Tribal and impoverished regions often lack even a minimal cadre of educators; one report cites districts with up to a dozen schools each having no permanent teachers. Contractual “guest” teachers or Shiksha Mitras (community instructors) fill some gaps, but coverage is uneven.

This teacher scarcity has serious implications for foundational learning. Without enough trained teachers, early grades struggle to deliver basic literacy and numeracy. Many schools resort to multi-grade teaching or overburdened teachers, diluting individual attention. Studies show that a high share of learning time is lost when teachers are absent or juggling multiple grades. Ultimately, rising school enrolment (now >95% among 6–14 year olds) has not fully translated into basic skills for children.

In short, India’s quantitative gains in enrolment now risk being undermined by inadequate teacher capacity and staffing.

Systemic Challenges in Teaching Quality and Deployment

Beyond sheer headcount, systemic issues constrain teaching quality in foundational grades. Pre-service training remains weak: a proposed overhaul of the Bachelor of Elementary Education (B.El.Ed) degree raised alarms among experts that it could shrink the pipeline of teachers. Many current teachers lack specialised FLN methods; rote instruction still dominates classrooms despite new pedagogical goals. Over 70% of teaching time is spent on traditiona, rote pedagogy often because curricula and teacher preparation emphasise coverage over comprehension.

Teacher deployment is also uneven. Urban or better-off districts often have surplus or qualified staff, while remote areas rely on untrained local hires. Research on India’s para-teacher programmes (e.g. Shiksha Karmi in Rajasthan) notes that these local educators boost attendance and community ties precisely because they share language and background with students. However, para-teachers often have lower pay, minimal training and tenuous contracts – factors that undermine retention.

Even regular teachers face challenges: delayed recruitment drives, inflexible transfers and uncompetitive salaries lead many to leave or remain absent. Haryana, for example, has had to shuffle teachers (making Hindi specialists teach English) and resort to online lectures for science due to acute staff gaps.

Retention and motivation problems compound these issues. Teacher absenteeism is endemic (often cited around 25–40% nationally) and many educators perform non-teaching duties or manage classes with 40–50 students. These factors reduce instructional time. About 45% of classroom time is lost to such disruptions. Even when teachers are present, insufficient support and outdated training mean they are ill-equipped to teach FLN.

A study found that only about one-third of teachers felt their in-service training was useful. In short, India’s education system currently prioritises inputs (buildings, enrolment numbers, teacher counts) over actual learning outcomes. This disconnect – combined with policy inertia – means that without external support, many early-grade students may enter Grade 3 without the reading and math foundations they need.

NGO-led Solutions for Foundational Learning Gaps

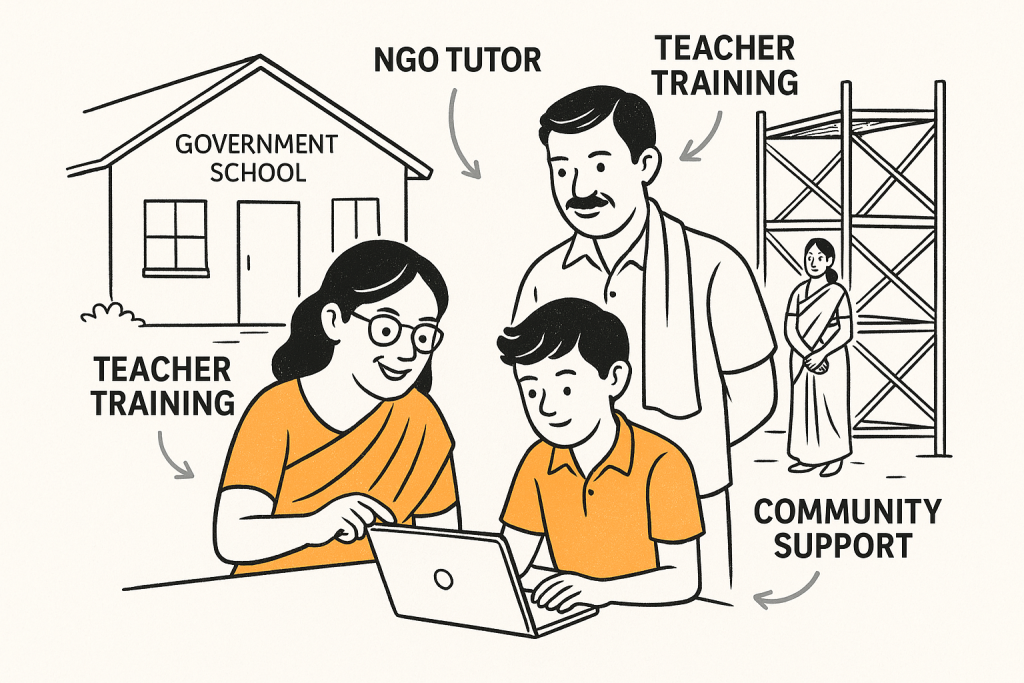

NGOs have stepped in to bridge these systemic gaps, tailoring grassroots solutions where public systems fall short. Their proximity to communities and flexibility allow them to pilot and scale innovative teaching models. Broadly, NGOs contribute in ways such as supplemental instruction, community educators, teacher training, digital resources, localised curricula and mobilising parents/community.

For example, NGOs often operate after-school or bridge classes to provide remedial and enrichment teaching outside the formal school timetable. These programmes (like Pratham’s renowned Teaching at the Right Level initiative) group children by learning level rather than age, ensuring that all basics are covered. Rigorous evaluations (e.g. J-PAL studies of the “Balsakhi” volunteer-tutor program) show that such remedial tutoring significantly lifts reading and math scores.

- Supplemental/Remedial Teaching: NGOs set up learning camps, “bridge schools” or study centers that hire local instructors or volunteers. These centers focus on foundational skills – teaching children to read simple stories or solve basic arithmetic through activity-based methods. For instance, Pratham’s TaRL volunteers in many states have demonstrated large learning gains at low cost. Similarly, small local NGOs organise mid-day learning clubs or distribute simple workbooks to reinforce what under-staffed schools cannot cover. These interventions effectively add instructional time and personalised attention, helping children catch up.

- Community-based Educators: Many NGOs recruit and train community educators – often local youth or mothers – to serve as paraprofessional teachers. Because they speak the local language and live in the village, these educators can engage closely with students and families. In India’s history, models like Rajasthan’s Shiksha Karmi and UP’s Siksha Mitra show that local teachers improve attendance and link schools to their communities. Newer NGO programmes echo this: local women literacy workers might visit homes to teach alphabets or youth serve as “learning coordinators” in multigrade classes. These community educators do not fully replace certified teachers, but they multiply human resources and keep classrooms functioning when official teachers are scarce.

- Teacher Capacity Building: NGOs run extensive training and mentoring programmes for existing teachers, with a focus on FLN pedagogy. They conduct in-service workshops on interactive and activity-based methods, classroom management and use of local materials. For example, Smile Foundation’s education arm hosts training camps in STEM, storytelling and child-centered teaching (see below). Other NGOs pair experienced educators with government teachers for peer learning. Research shows that experiential, classroom-based training helps teachers shift away from rote drills to more engaging techniques. Importantly, NGOs often work within government schools – modelling lessons or providing co-teaching support – so that over time teachers absorb these practices.

- Digital and EdTech Solutions: Leveraging technology, NGOs are deploying smart classes, tablets and digital libraries to enrich understaffed classrooms. Smart boards with preloaded FLN content let a single teacher deliver multimedia lessons on letters, numbers and stories. Mobile apps and offline learning devices engage children in basic reading/math games even when teachers are not present. For instance, Smile Foundation partners and other NGOs install solar-powered digital kits in rural schools, offering animated lessons on local language and numeracy. These tools don’t replace teachers, but they serve as aides – making lessons self-paced and visually engaging. As one analysis notes, NGOs increasingly provide smart TVs or tablets with curriculum-aligned content, thus empowering teachers to deliver richer lessons.

Students in a Smile Foundation smart classroom engage with interactive digital lessons. NGO-supported tech (e.g. tablets, smartboards) can enrich foundational literacy and numeracy instruction when teachers are few.

- Localised Curriculum and Materials: NGOs often create or distribute learning materials that resonate with local context. This includes storybooks in regional languages, math kits using locally available objects and picture-sheets aligned to the cultural setting. By providing these, NGOs help teachers (who may lack resources) make lessons relatable. For example, some NGOs compile collections of folk tales or primers in tribal dialects to ensure early literacy is home-grounded. These resources compensate for gaps in official textbooks and support teachers in multi-grade classes.

- Community Mobilisation: Recognising that teacher shortages often worsen when parents undervalue early schooling, NGOs mobilise families and community leaders. They form parent groups or mothers’ committees to monitor learning and keep children in school. By raising awareness of FLN (e.g. educating parents on the importance of grade-appropriate reading), NGOs boost enrolment and attendance – indirectly justifying more teachers. They also advocate locally (with panchayats or district officials) to press for teacher appointments. This grassroots advocacy has prompted some states to launch accelerated recruitments. Overall, as one NGO analysis notes, “from improving infrastructure to training teachers, from distributing digital resources to mobilizing community participation, NGOs are making education not just accessible, but meaningful”.

Together, these NGO roles create complementary scaffolding around government schools. They do not aim to replace public schooling but to reinforce it: supplementing instruction where teachers are thin, raising teacher skills where training is weak and leveraging technology and community support to compensate for resource gaps.

Smile Foundation’s Mission Education: A Case Study

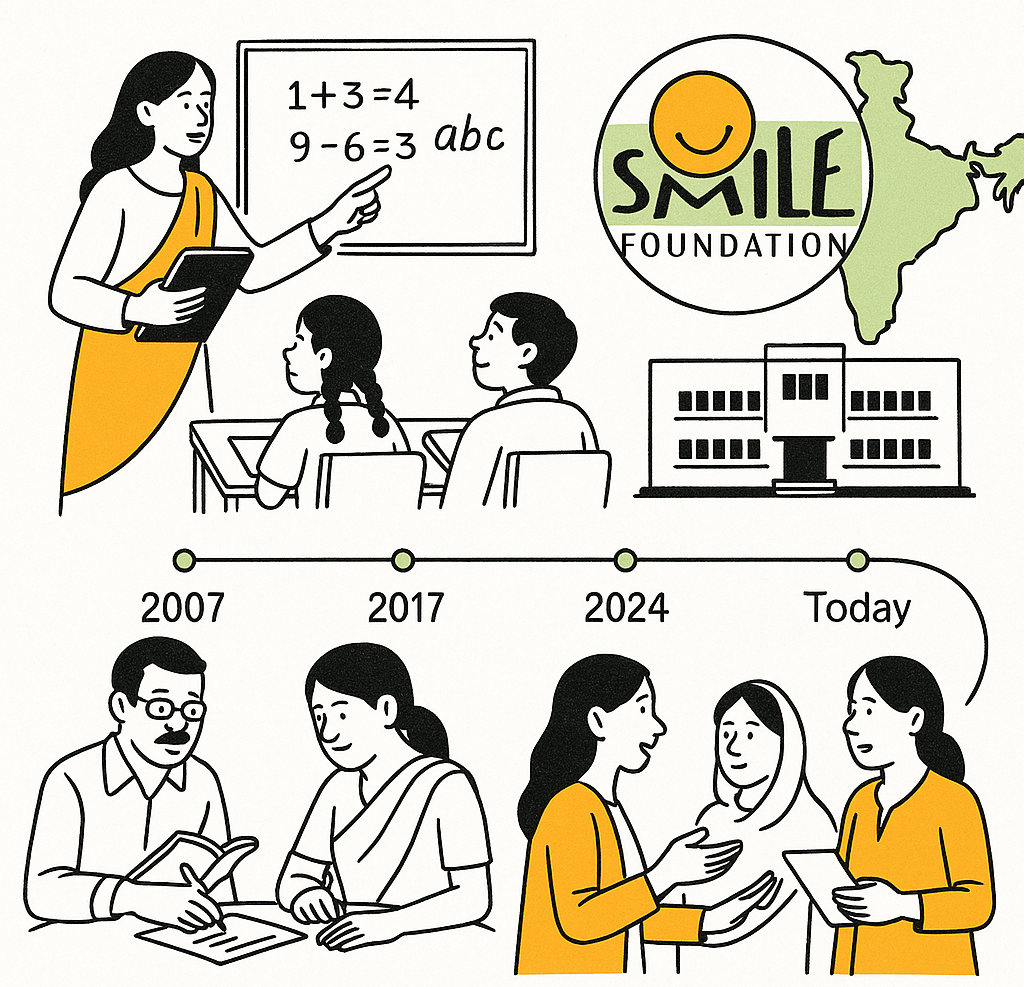

Smile Foundation’s Mission Education is a prominent example of how an NGO can tackle multiple dimensions of the teacher gap in FLN. Operating in over 27 states, Smile’s education programmes directly reach ~1.6 lakh children through 735 Mission Education Centres (spanning pre-primary to senior secondary) and by supporting 12,660+ government schools. The NGO emphasises a four-pronged, child-centred approach: investing in infrastructure and digital tools, building teacher capacity and engaging communities.

In tech-enabled learning environments, Smile installs digital classrooms in supported schools. These “smart” rooms come with projectors, interactive whiteboards or tablets loaded with curriculum-aligned content in local languages. Children in these classes experience animated storytelling, phonics songs and math games – an approach quite different from rote lessons.

Over the past year, we established multiple digital labs as part of enriching the learning environment. Teachers receive training to operate this equipment, so technology augments rather than replaces them.

Simultaneously, teacher development is a key pillar. Smile conducts regular training sessions (often in workshops or onsite demonstrations) for government teachers in its network. In the last year, Smile facilitated 86 training sessions attended by 482 teachers and 116 school heads. These sessions cover modern pedagogies like activity-based learning, foundational literacy methods, STEM education, classroom management and lesson planning. The focus is on making classes interactive and inclusive.

Notably, Smile aligns its training to the NIPUN Bharat and NEP 2020 goals of FLN, ensuring teachers learn how to engage early graders effectively. By upskilling hundreds of local teachers each year, Smile helps fill the “training gap” that public systems often neglect. This empowers teachers who remain in place, so that even in understaffed schools, the available educators can deliver higher-quality FLN instruction.

Community involvement is the third prong of Smile’s model. They mobilise parents and local stakeholders through mother-teacher associations and community meetings. By involving mothers’ groups and panchayats, Smile encourages communities to monitor schooling, prevent dropouts and even identify potential local candidates to train as volunteer aides. In many villages, Smile staff work with village education committees to track which children need help and to ensure classrooms are functioning. This community focus not only keeps children in school but also creates accountability for teacher attendance and performance. In areas where official teacher attendance is erratic, community vigilance ensures that programmes like Smile’s do reach the intended students.

Finally, Smile directly provides learning materials and support to children. It supplies notebooks, textbooks, math kit tools and storybooks in Hindi and regional languages. It also establishes STEM and language labs in some centers, encouraging self-learning. By filling resource gaps, Smile reduces one factor that often stretches teachers thin (improvising lessons without materials).

In sum, Smile Foundation’s Mission Education programme illustrates the multi-pronged NGO approach: infrastructure + pedagogy + community. The combination of digital classrooms, teacher training and grassroots outreach helps mitigate the effects of teacher shortages. For example, a village primary school supported by Smile may still have only 2 government teachers, but those teachers are backed by smartboards and local teaching aids; they have received fresh training in FLN methods; and enthusiastic mothers’ groups keep children engaged. This integrated support has led to anecdotal improvements: Smile reports higher attendance and rising reading scores in its partner schools.

Other NGOs play similar roles on different scales. For instance, Pratham’s TaRL volunteers and Learning Links Foundation’s Sambal Shiksha programme also supplement regular teaching with tailored FLN camps and training. Tech-focused NGOs (or CSR initiatives) provide tablets loaded with offline reading apps to thousands of rural schools. Meanwhile, community mobilisers like Teach For India alumni or Rural Volunteers help run bridge classes.

Across these varied interventions, the thread is clear: NGOs are filling the chasm left by structural teacher shortfalls. They do so by multiplying adult presence in schools (through volunteers and community teachers), enriching what each teacher can do (through training and tech) and bringing learning resources directly to children. While government reforms aim to systemically improve FLN, on-the-ground change often hinges on such NGO action. By tailoring solutions to local challenges – and continuously adapting to on-site realities – NGOs ensure that even in hard-hit regions, children have a fighting chance at basic reading and math.