For decades, India has been cast in a global role shaped by its comparative advantage in low labour costs: call-centres, back-office support, basic manufacturing. This “cheap labour” label boosted jobs and foreign investment, but it also locked in constraints — low wages, limited mobility, under-production of high-value skills and a global perception hard to shake off. As automation, artificial intelligence, global supply-chain reconfiguration and shifting trade dynamics reshape opportunity, India faces a pressing question: can it pivot from being the world’s low-cost labour pool to being recognised for high-value skills and innovation?

The Promise: What India Has On Its Side

India has several strengths that suggest this pivot is feasible, even urgent.

- Demographics and Young Talent Pool. India is set to have the world’s largest working-age population by 2030. This offers not just numbers, but potential — if young people are trained and matched with the right opportunities.

- Rise of Innovation & Start-ups. The start-up ecosystem has grown dramatically. India now hosts unicorns in fintech, edtech, health tech, deep tech; investors are increasingly interested in India not just as a low-cost base but as a source of innovation. Enhanced infrastructure like better internet connectivity, improved logistics, growing digital literacy supports this.

- Policy Support & Skill Programmes. Several government schemes aim to upskill India’s workforce:

- Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana (PMKVY): Designed to provide industry-recognised skills to millions.

- National Apprenticeship Promotion Scheme (NAPS): Encouraging firms to take on apprentices, bridging formal vocational training and workplace practice.

- Skill India Digital Hub, Skill India International Centres: Efforts to bring global standards, digital tools and cross-border collaboration into India’s skilling framework.

These programmes show intent. But intent must translate into structural change. Otherwise, India risks being left behind in the global economy, where high-value skills, automation and quality matter more than just labour cost.

The Evidence: Where India Stands Now

To assess whether the move from low-cost labour to high-value skills is happening, or even possible, it helps to look at recent data:

- Female Labour Force Participation (FLFPR): In the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) 2023-24, the female LFPR rose to 41.7%, up from about 23.3% in 2017–18. (Press Information Bureau) Still, formal wage or salaried employment among women remains low; many are in self-employment or unpaid work. (Reuters)

- Prevalence of Low-Competency Occupations: The Institute for Competitiveness (IFC) report, Skills for the Future: Transforming India’s Workforce Landscape, found nearly 88% of India’s workforce in 2023-24 is in low-competency occupations. Only small shares are in high-skill (Skill Levels 3 & 4) jobs. (The Economic Times)

- Training Gaps: According to PLFS and related reports, only ~4.1% of those aged 15-59 have received formal vocational training. Approximately 30-odd percent have training of some kind, often informal or on-the-job; but over 60% have no formal or informal training. (SPRF)

- Mismatch between Training & Employability: Even among those who receive training, many find their skills don’t match what employers want. A 2025 report noted that formally trained individuals see unemployment rates around 17%, higher than for some informally trained workers in certain contexts. (India Development Review)

These statistics show that while there is momentum, much of the current participation is in lower skill, lower value work — not yet a structural shift toward high-value skills. Unless addressed, this mismatch threatens both social inclusion and economic competitiveness.

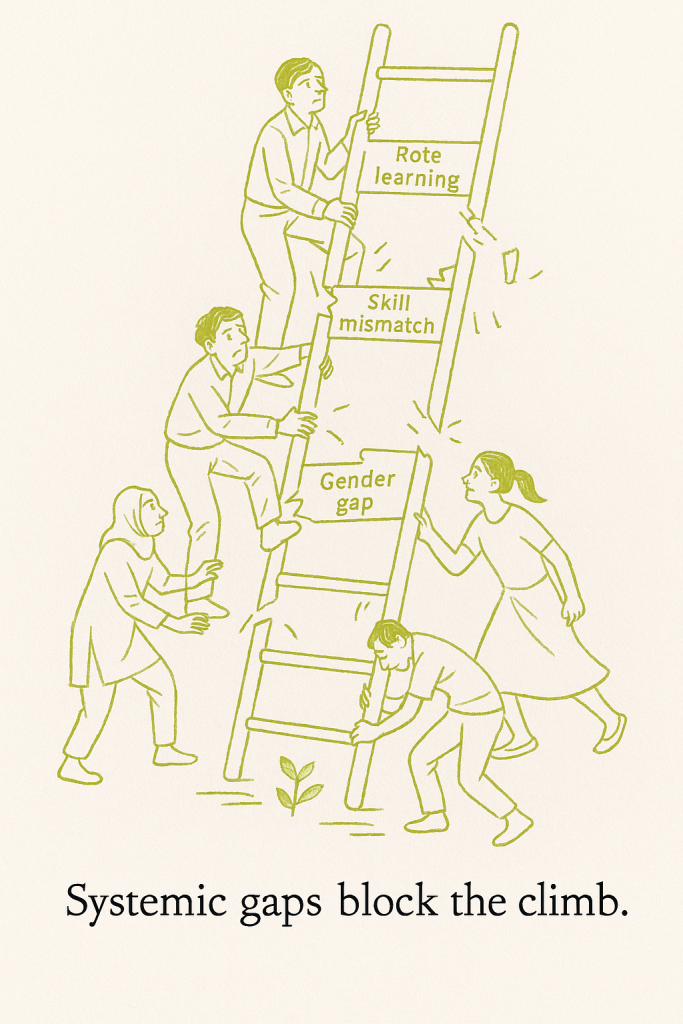

Barriers to Moving Up the Value Chain

Bridging the gap from low-cost labour to high skill is about reworking multiple structural and cultural barriers.

- Education System Limitations. Schools still focus heavily on rote learning, standardised exams and theory. Skills like critical thinking, communication, creativity, problem solving in context are often neglected. Employers frequently report that graduates lack those soft and adaptive skills.

- Limited High-Skill Job Creation. Many job openings remain in semi-skilled or low-skilled sectors. Employers may be reluctant to invest in higher-skill roles if labour remains cheap; sometimes automation or overseas sourcing appears cheaper at scale, but this risks India losing out on high-margin work.

- Inadequate Industry–Academia Linkages. Vocational curricula don’t always map to what industries actually require. Internships, apprenticeships, hands-on training remain uneven in quality and reach.

- Inequality & Exclusion. Women, rural youth, disadvantaged caste groups and those in informal sectors often are last to receive quality training, last to gain access to formal employment. Female participation remains low in many states, and when women work, pay gaps are persistent. Added constraints: safety, mobility, care responsibilities.

- Cultural & Perceptual Barriers. Persistent perception that high-value skills are only for elite institutions; risk aversion among poor families who favour tried-and-tested low-skill work over uncertain investment in training or entrepreneurship. Social norms, especially around gender, can restrict who goes to which training, or travels for work.

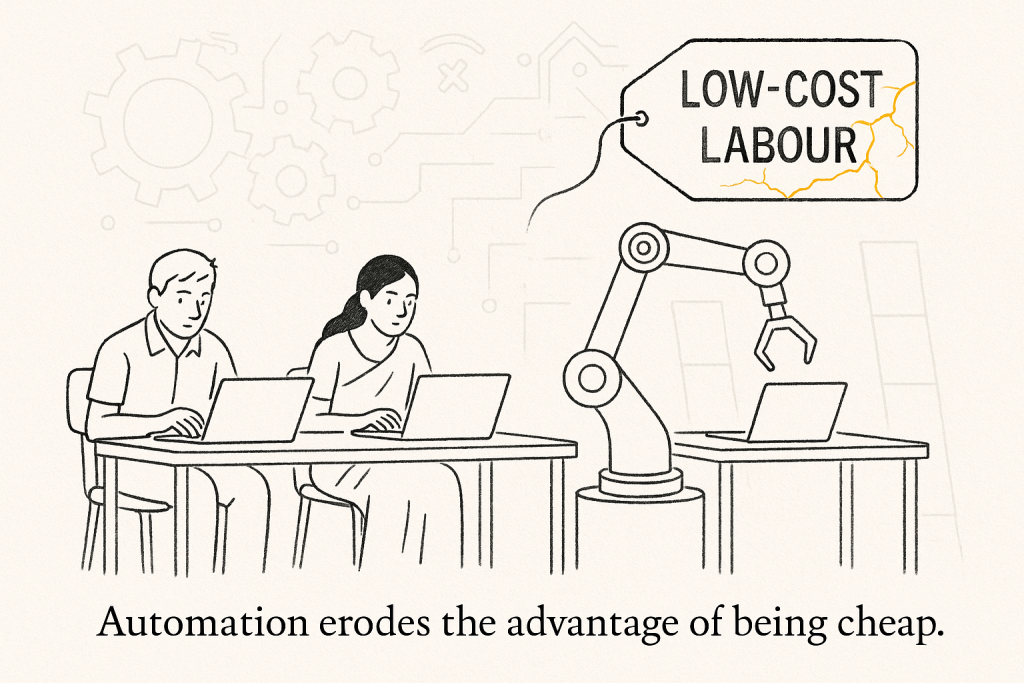

- Technology Displacement & Automation Risk. As routine or repetitive tasks are automated (e.g. basic call centre roles, manual assembly), low-cost advantages erode. Without upgrading skills, many workers risk displacement.

What a High-Value Skill India Needs

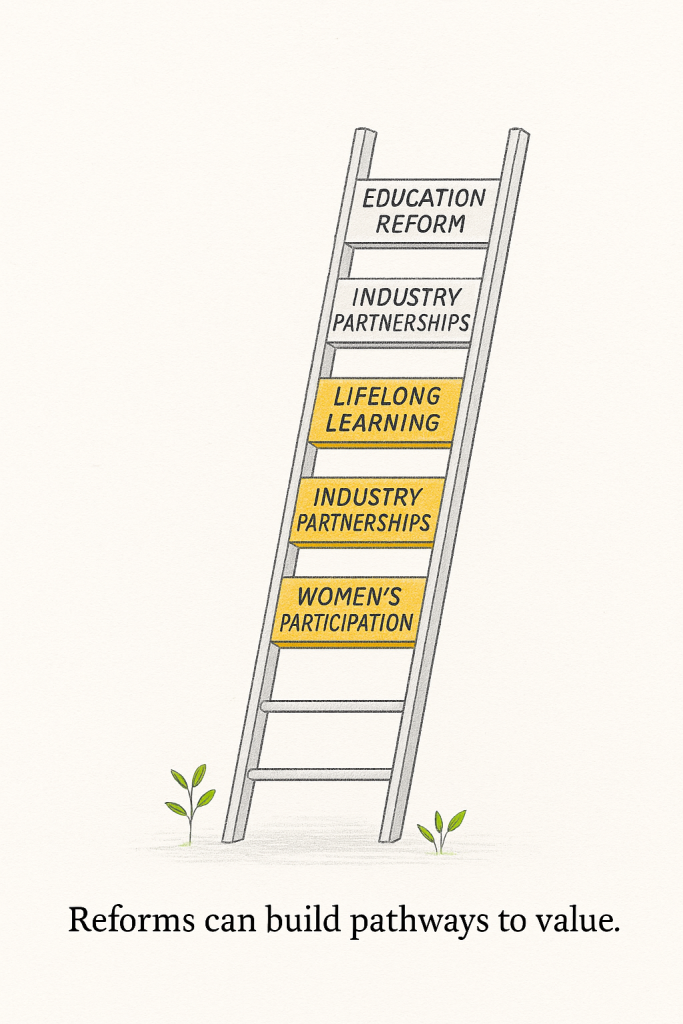

If India is to transcend its low-cost labour label, it needs a strategy that is multi-pronged: policy, finance, culture and delivery must align.

- Revamp Education & Vocational Training.

- Curriculum redesign: Integrate problem-solving, critical thinking, digital literacy from early schooling.

- Expand formal apprenticeship programmes: NAPS and related schemes should be scaled, with incentives for firms to absorb apprentices into meaningful roles.

- Standardise competency levels: Clear, transparent frameworks (e.g. what “Skill Level 4” means in different sectors) so employers trust the skills certificate.

- Strengthen Industry Partnerships.

- Sector councils or boards that include employers, training institutions, government, to jointly map future demand.

- Co-design curricula; embed internships, project-based learning and live exposure.

- Encourage firms to invest in employee upskilling, through tax incentives, CSR or public matching funds.

- Promote Lifelong Learning & Micro-credentialing.

- Digital platforms, modular short courses, stackable credentials can allow workers to upskill in small increments.

- Encourage continuous upskilling especially in emerging fields: AI/ML, cybersecurity, renewable energy, advanced manufacturing, biotech.

- Support for Women, Rural & Marginalised Youth.

- Remove barriers: affordable childcare, accessible transport, safe workplaces.

- Gender‐sensitive training programmes; outreach in rural and semi-urban areas.

- Scholarships, stipends and connectivity support (internet, devices) for remote or hybrid learning.

- Policy & Regulatory Incentives.

- Encourage foreign direct investment (FDI) in high-value sectors with stipulations for local skill transfer.

- Incentivise companies to raise job quality, not just job numbers: formal contract work, wage parity, social protection.

- Reinforce enforceable standards: for training quality, accreditation, worker safety, gender equity.

- Culture & Mindset Change.

- Media, universities, community leaders should promote narratives of high-value work not just in urban or elite areas.

- Career guidance in schools that shows students the possibility of high-value careers in different geographies and for different kinds of backgrounds.

- Role models: showcasing success stories of individuals (especially from rural/underprivileged backgrounds) who have made the leap.

Smile Foundation’s Role

To illustrate what is possible, the work of Smile Foundation and its various employability and training initiatives provides both hope and lessons.

- STeP (Skill Training & Employability Programme): Focused on connecting low-income setup youth to jobs in sectors with growth and higher value — retail, digital marketing, healthcare, BFSI (banking, financial services, insurance). Beyond hard technical skills, STeP places emphasis on soft skills: spoken English, interview readiness, customer service. These are precisely the skills employers say they need but often do not find.

- iTrain on Wheels: By bringing training into underserved areas (rural or semi-urban) and in more practical trades (painting, electrical, etc.), this reduces costs and accessibility barriers. This helps people gain directly employable skills rather than just theoretical knowledge.

- Partnerships & Scale: Smile Foundation works with hundreds of organisations to ensure training aligns with real job opportunities. Aligning with government initiatives (Skill India etc.) helps leverage scale. The combination of local outreach, hands-on skill training and linkages to employment gives its programmes high potential.

These models show that credible pathways exist. But current reach is limited relative to the scale of the challenge; many more millions still do not receive formal training or do not find jobs commensurate with what they learn.

What the Data Suggests for the Near Term

- According to the PLFS (2023-24), only about 50.2% of workforce has education at or above secondary level.

- A disturbing trend: in 22 of 36 states and union territories, the growth rate of highly skilled individuals (Skill Levels 3 & 4) has declined by more than 5% between 2017 and 2022.

- Only ~2-3% of the workforce is at the highest skill levels. Most have low to semi-skills.

- For women, despite growth in participation, most of the increase is in informal/self-employment or in sectors with lower earnings and weaker social protection. Formal wage/salaried jobs remain elusive for many.

Why This Shift Matters: Beyond GDP Growth

Moving from low-cost labour to high-value skills is not merely an economic ambition — it has deep implications for equity, resilience and India’s global standing.

- Better incomes, less inequality. High-value skills tend to command higher wages, more stable employment, social protection. This helps reduce income inequality and poverty, especially in rural areas or among marginalised groups.

- Global competitiveness and moving up value-chains. In sectors like electronics, pharmaceuticals, AI, renewable energy, supply chains reward precision, innovation, regulatory compliance. India must produce work that is not just cheap, but of high quality and high trust.

- Resilience to automation and shocks. As routine jobs are automated, those with only low skills are most vulnerable. High-value skills create adaptability: ability to shift fields, to move into roles that machines can’t easily replace.

- Social transformation. Skills and work are not only sources of income but of status, agency, dignity. For women, achieving high-value skills means more autonomy, greater voice in households, better health and education outcomes for families.

India stands at a crossroads. It can continue leveraging its cost advantage, keeping its labour market saturated by low-value jobs or it can shift decisively toward developing, certifying and scaling high-value skills. The cost of inaction is high: slower growth, persistent inequality, vulnerability to global shifts.

To succeed, India will need:

- Focused investment in formal and informal training, especially for women and marginalised communities.

- Strong partnerships between government, private sector, civil society.

- Incentives not just for job creation, but for job quality and upward mobility.

- Cultural shifts: acceptance of lifelong learning; respect for vocational and technical work; breaking stereotypes about what fields are “prestigious”.

If India makes this shift thoughtfully, inclusively, and ambitiously, it can move from being “the world’s low-cost labour provider” to being its trusted source of high-value, cutting-edge talent. The journey is challenging — but it is not beyond reach. And the payoff will be not just economic growth, but a more just, resilient and future-ready society.