Imagine a community where one child is too weak from malnutrition to play, while next door another is battling childhood obesity and early diabetes. It sounds like a plot twist in a dark comedy, but it’s reality in many parts of the world today. This “double burden of malnutrition” means the paradoxical coexistence of undernutrition (not getting enough healthy food) and overnutrition (eating too much of the wrong foods).

How did we end up with such a nutritional yin-yang? More importantly, what’s being done about it, let’s dig in.

In India, conversations on nutrition always peak during Poshan Maah, the national nutrition month. It’s the perfect time to spotlight this paradox and ask: how can a country simultaneously struggle with malnutrition and obesity? And more importantly, what can be done about it – especially for mothers and children, the most vulnerable groups?

What is the “Double Burden” of malnutrition?

In the not-so-distant past, the word “malnutrition” conjured images of skinny, stunted children with not enough to eat. That’s still a critical problem – millions of children worldwide are undernourished – but now we have a plot twist. The double burden of malnutrition refers to situations where undernutrition and overnutrition exist together. Think of it as malnutrition’s way of hedging its bets: if lack of food doesn’t get you, excess junk might!

According to the World Health Organization, this double burden can occur within populations, households or even individuals. For example:

- Within a population: A country might have a high rate of childhood stunting and a growing rate of adult obesity at the same time.

- Within a household: One family could have an underweight child and an overweight parent living under one roof – a perplexing dinner table scenario where one person needs more calories and the other needs fewer (and healthier) calories.

- Within an individual: Yes, a single person can experience both forms of malnutrition. For instance, someone can be overweight but deficient in essential vitamins and minerals (a phenomenon sometimes called “hidden hunger”). Picture someone who lives on soda and chips – they may be heavy on the scale but still malnourished in nutrients.

In all its forms, malnutrition is basically an imbalance – either not enough nutrients or too many (especially too many empty calories). It’s like your body is Goldilocks, searching for the “just right” diet, but constantly getting either a porridge that’s too little or too much cake instead.

The global paradox: Undernourishment vs. obesity

If this sounds like a strange paradox, the numbers confirm it. Globally, malnutrition now has two faces. On one side, we have chronic undernutrition; on the other, rising overweight and obesity. Consider these eye-opening statistics:

- Under-nutrition by the millions: As of 2022, about 149 million children under five worldwide are stunted (too short for their age due to chronic undernutrition) and 45 million are wasted (dangerously thin from acute undernutrition). Nearly half of all deaths in under-five children are linked to undernutrition – a sobering fact that mostly hits low-income countries.

- Over-nutrition catching up: Meanwhile, 37 million children under five are overweight globally. And it’s not just kids – about 2.5 billion adults were overweight in 2022, including 890 million classified as obese. On the flip side, 390 million adults were underweight. Yes, you read that correctly: there are hundreds of millions of underweight people and billions overweight, all at the same time on the same planet.

This is the very definition of the double burden – stubborn undernutrition and soaring obesity co-existing worldwide. It’s as if the global community is on a see-saw where one side of malnutrition won’t budge without the other tipping over. To put it more bluntly, we live in a world where some people are dying because they can’t get enough food, while others are dying because they can’t stop eating unhealthy food. It’s a nutritional irony of our times.

Double trouble in India and other developing countries

The double burden is especially evident in countries undergoing rapid economic and lifestyle changes. Take India as a prime example – a country often highlighted in discussions of malnutrition. India has long battled high rates of undernutrition and despite progress, it still has staggering numbers of undernourished children. In fact, roughly one in every three malnourished children in the world lives in India. According to national surveys a few years back, about 38% of Indian children under 5 were stunted, 46% underweight and 16% wasted – contributing to India’s unfortunate distinction of having the largest number of malnourished kids globally.

But here comes the double burden twist: even as undernutrition persists, over-nutrition is rising in India. The same nation with widespread malnutrition is also seeing growing obesity, especially in adults. Recent data show that about 24% of Indian women (15–49 years) are overweight or obese. Urban areas in India are witnessing more cases of childhood obesity and diabetes, even as rural areas struggle with underweight children. Talk about an identity crisis – India’s nutritional profile ranges from severe calorie deficit to calorie surplus depending on where you look.

This pattern isn’t unique to India. Many developing countries – from parts of Africa to South-East Asia and Latin America – now deal with a “two-front war” on malnutrition. As economies grow and diets shift from traditional foods to processed, high-calorie foods, waistlines expand even among populations that still face poverty and micronutrient deficiencies. Health experts call this the nutrition transition, where lifestyles move from active, whole-food diets to sedentary lifestyles with processed foods. The result? Grandma might be undernourished, while her grandchild is overweight. Or an overweight, anaemic mother may give birth to an underweight baby – thus continuing a vicious cycle.

It’s a bit like a tale of two meals: one meal is too meagre to sustain a child and the very next meal is a sugary soda and chips contributing to obesity. Both are lacking the quality nutrition needed for health and both can occur in the same community. No wonder public health officials sometimes scratch their heads – and then roll up their sleeves to tackle both problems together.

Why does the double burden happen?

How on earth do we end up with malnutrition at both extremes? There are several underlying causes fueling this double burden and (warning) some are on the serious side – but we’ll try to explain in digestible bites:

- Poverty and inequality: In many regions, economic growth has been uneven. So you get pockets of prosperity alongside extreme poverty. Wealthier (often urban) populations start consuming more high-fat, high-sugar foods and become less physically active – leading to weight gain. Meanwhile, poorer communities still struggle with undernutrition. It’s not unusual to find, say, an urban slum where a few residents can afford fast food (and become overweight) while their neighbours cannot afford enough food (and remain undernourished). Poverty also means limited access to diverse, healthy foods, driving both malnutrition and reliance on cheap junk calories.

- Changing diets (Nutrition transition): Globally we are witnessing a shift from diets rich in fibre, fruits and vegetables to diets high in processed foods, oils, sweetened beverages and meats. These foods are often calorie-dense but nutrient-poor. They fill the stomach (and add weight) but don’t provide the vitamins or minerals a body needs. So someone might get overweight on a diet of white rice, fried snacks and sugary drinks, yet become deficient in iron or vitamin A. As one study noted, as countries develop economically, undernutrition tends to decrease – but obesity increases markedly at the same time. We’re basically swapping one problem (not enough food) for another (too much unhealthy food) unless nutrition education keeps up.

- Urbanisation and lifestyle: City life often means less physical activity (desk jobs, anyone?), more stress and greater exposure to fast food outlets than fresh farm produce. The result is a recipe for weight gain. At the same time, rural areas might still lack access to sufficient food or healthcare. Also, urban poor might fill up on cheap street foods that are high in carbs/fats but low in nutrients, leading to a condition humorously dubbed “skinny-fat” – normal weight or overweight but malnourished in nutrients. It’s like being overfed and undernourished simultaneously.

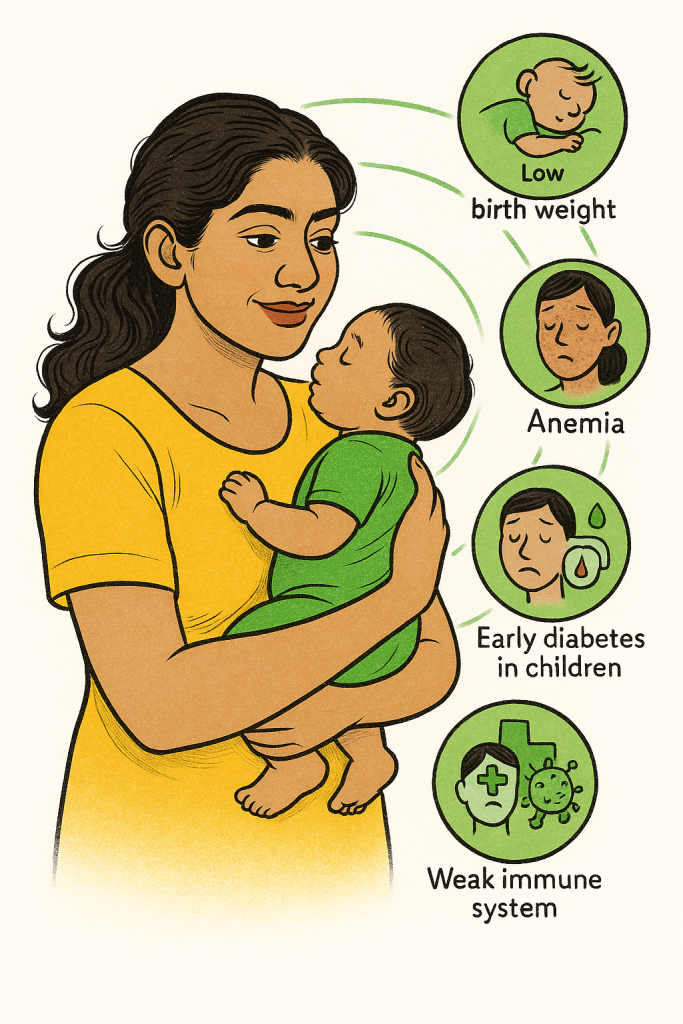

- Generational cycle: Here’s a less funny fact – an undernourished child can grow up with health problems that make them prone to obesity later. For instance, if a foetus doesn’t get enough nutrition (say the mother was undernourished during pregnancy), the child’s body might become super efficient at storing fat (a survival mechanism). Later in life, if that child eats a high-calorie diet, they might easily become overweight or develop heart disease. Meanwhile, women who become overweight (yet nutrient-deficient) can have complications in pregnancy and risk giving birth to babies who are underweight or have developmental issues. This intergenerational cycle means undernutrition and overnutrition can feed into each other across a family’s timeline.

- Lack of nutrition education: Sometimes, people simply don’t know what eating right means – especially if they’ve transitioned from food scarcity to having more food available. It’s easy to equate “chubby child” with “healthy child” in some cultures, so diets heavy in fried foods or sweets might be seen as a sign of prosperity. Conversely, parents might not realise that an inexpensive local vegetable is more nutritious than an expensive packet of noodles. When education levels are low, even relatively well-off families can make poor nutrition choices, leading to obesity and micronutrient deficiencies. As one research finding intriguingly noted, even higher maternal education in India doesn’t always protect against the double burden – possibly because education is not translating into better nutrition knowledge or lifestyle (an educated working mom might have a sedentary job and rely on convenient processed foods). In short, knowing how to eat healthy is as important as having access to food.

So, the double burden is essentially malnutrition in stereo – one channel is poverty and lack of food, the other is dietary excess and poor quality food. The two can play simultaneously. The challenge is that tackling just one side (for example, just eliminating undernutrition) without guarding against the other (like unhealthy eating) can backfire. Countries that successfully reduced famine have seen spikes in obesity and diabetes if diets became too rich in sugars and fats. It’s like a see-saw that needs balancing – focusing only on undernutrition might accidentally tip the population into an obesity epidemic. The goal has to be finding the healthy middle ground – ensuring everyone gets enough and the right kind of food.

Impact on mothers and children: The 1-2 punch

The double burden of malnutrition hits hardest where vulnerability is already high – especially among mothers and children. This duo has a special place in nutrition discussions because a mother’s health directly affects her child’s, starting even before birth.

Mothers: Consider an expectant mother in a low-income community. If she’s undernourished (perhaps anaemic and underweight), her baby might be born underweight or premature, immediately at risk of growth and developmental problems. Now imagine another mother who is overweight but nutrient-deficient (yes, that’s possible – living on polished rice and maybe sugary tea, for instance). She might face gestational diabetes or hypertension and her baby could grow larger than normal in the womb or conversely also face malnutrition if the quality of her diet is poor. In both cases, the child’s future is impacted. In India, over 52% of pregnant women are anaemic (low in iron) – that’s a form of malnutrition that can cause fatigue, complications in childbirth and affect the baby’s growth. At the same time, rising obesity among women means more cases of diabetes and C-sections, which interestingly have been linked to higher odds of mother-child double malnutrition (one study found mothers with C-section births had higher risk of an undernourished child combined with maternal overweight). It’s a lose-lose situation we must turn into a win-win.

Children: Now zoom in on the kids, the most visibly affected by malnutrition. Undernourished children (stunted, wasted, etc.) face impaired immunity, frequent illnesses and struggles in school. They’re the kids who might be too tired to play or concentrate. Meanwhile, an overweight child (yes, those exist in poorer communities too, often due to cheap junk food) faces a different set of issues: risk of early onset diabetes, joint problems and social stigma. And here’s the kicker – these problems can be neighbours. It’s not uncommon in, say, an urban Indian slum or an African city, to see a skinny child and an overweight child in the same playground. Undernutrition in early life can also prime a child’s body to store fat more efficiently if food becomes abundant later – leading to adult obesity. It’s almost cruel: a child who survives undernutrition might later in life succumb to an obese-unhealthy lifestyle if diets aren’t improved. As the Smile Foundation team observes, “The children most affected by malnutrition are the ones whose mothers are themselves victims of ill health.” It’s a cycle of weak moms, weak babies and a weak future – unless we intervene decisively.

To paint a more optimistic picture: improving a mother’s nutrition is like a two-for-one deal – you get a healthier mom and a healthier child. That’s why many nutrition programmes (including Smile Foundation’s, which we’ll discuss next) focus on maternal and child nutrition together, often termed “MCH” in development jargon. It targets that critical 1000-day window from pregnancy to the child’s second birthday, where the right interventions can prevent both stunting and future obesity. In a way, ensuring balanced nutrition for women and kids is an antidote to the double burden: it prevents undernutrition early on and establishes healthy eating patterns that ward off overnutrition later.

Smile Foundation’s approach for Poshan Maah 2025: Tackling malnutrition from all angles

Enough about problems – let’s talk solutions! This is where organizations like Smile Foundation roll up their sleeves to combat malnutrition in all its forms. We have been actively addressing nutrition through a variety of programmes. And the secret sauce to our approach is integration – recognising that food quantity and food quality must go hand in hand.

Smile Foundation’s nutrition initiatives are linked with education, health and women’s empowerment, creating a holistic model. For instance, one of our nutrition campaigns, “Plate Half Full,” was designed to ensure children not only attend school but also receive a nutritious meal every day. After all, what good is schooling on an empty stomach? As Mr. Santanu Mishra, co-founder of Smile Foundation, aptly put it, “Plate Half Full is a programme designed to address the challenge of nutrition and education in young children. It comes with a promise of nutritious food along with regular school education, encouraging more kids to attend school in the lure of wholesome meals.”

In other words, feeding children well is a strategy to both improve health and boost learning outcomes – a win-win that tackles undernutrition (by providing food) and helps prevent future overnutrition (by instilling healthy eating habits early).

But Smile’s work goes beyond just school meals. Here are some key ingredients in our recipe for fighting malnutrition:

- Daily nutritious meals & health check-ups: Through our Mission Education centres, Smile Foundation provides underserved children with at least one wholesome meal every day and regular health camps every quarter. For kids like six-year-old Kiran in Maharashtra, India, this was life-changing. Kiran was visibly malnourished when she joined a Smile education centre – she was weak, undersized and so hungry that she had developed a habit of eating mud (yes, actual mud!) to fill her stomach. Her parents, daily-wage labourers, could barely afford one meal a day and Kiran’s health was failing. Once enrolled, she started receiving nutritious meals each day and basic medical care. The result? Over time, Kiran’s health improved, she became more active in class, and her attendance and learning ability shot up. Proper nutrition literally put the “smile” back in her childhood. Her story is not unique – thousands of children in Smile’s programmes show better growth and school performance once their bellies (and brains) are fed with the right nutrients.

- Nutrition education for families: You can’t fix malnutrition by food aid alone; mindset and knowledge have to change too. Smile Foundation knows this, so we conduct regular awareness sessions for parents and communities about health, hygiene and balanced diets. Imagine interactive street plays and catchy songs in villages about washing hands and eating your greens – that’s how Smile engages people without scolding or boring them. We hold workshops for mothers on how to grow kitchen gardens and cook low-cost nutritious recipes. Many parents in marginalised communities simply never learned what a balanced meal is – they might fill a child’s stomach with plain rice or bread, not realising the child also needs proteins and vitamins. By teaching mothers that a little bit of dal (lentils) or a few leafy vegetables can make a huge difference, Smile Foundation empowers families to fight undernutrition and prevent diseases. One fun example: mothers are shown how to make “power porridge” or other local dishes more nutritious by adding ingredients like peanuts or moringa leaves. Such education ensures that even when resources are scarce, they’re used smartly to maximise nutrition. And critically, this education also warns about the pitfalls of junk food, so as communities become economically better, they hopefully won’t trade malnutrition-by-undernutrition for malnutrition-by-junk-food.

- Community-based programmes and campaigns: Smile’s approach often involves the entire community. For example, we initiated “Cook for Smile” contests where top chefs and corporate leaders literally don an apron and cook healthy meals to raise awareness and funds. Involving celebrities and influencers like renowned Chef Vikas Khanna has added creative twists – Chef Khanna even developed a special nutritious laddoo (an Indian sweet) recipe for adolescent girls suffering from anemia. The laddoo, made of local ingredients like jaggery and sesame, was a big hit in Gujarat: over 15,000 of these iron-rich sweet balls were distributed to a thousand girls over 10 months, alongside iron supplements. More than 70% of those girls showed significant improvement in haemoglobin levels and BMI (a key indicator of healthy growth). Now that’s a sweet victory against malnutrition – literally!

- Integrated health and nutrition camps: In tackling maternal and child malnutrition, Smile Foundation often complements government initiatives. For instance, through projects like Nutrition Enhancement in Punjab and “Pink Smile” in Uttar Pradesh, they set up mobile health camps to screen women and children for anaemia and malnutrition on the spot. These camps don’t just screen – they treat and educate. If a child is found underweight, they might get referred for medical care and the mother gets counselling on feeding practices. If a woman is found anaemic, she’ll receive iron supplements and a lesson in cooking iron-rich meals. In one district (Sangrur, Punjab), Smile Foundation helped establish community kitchen gardens and added iron supplements to school meals; within six months, anaemia rates among schoolchildren plunged from about 40.6% to just 2.7% – virtually eliminating anaemia in some schools. That’s the power of an integrated approach: combine government resources (like mid-day meals and health workers) with community engagement (gardens, nutrition classes) and you get dramatic results. It’s like hitting malnutrition with a one-two punch.

- Focus on women and adolescent girls: Since mothers are key to breaking the malnutrition cycle, Smile runs targeted programmes under our women’s empowerment and health initiatives. We provide one-on-one counselling for expecting and new mothers on diet (what to eat when pregnant or breastfeeding), encourage exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months, and teach families about proper child feeding practices. In adolescent girls, who are future mothers, interventions like the laddoo project (called Project Sampoorna in Banaskantha, Gujarat) address anemia so that these girls don’t carry ill-health into motherhood Through peer education and school-based programmes, girls learn about nutrition, menstrual health and the importance of a balanced diet. The goal is to ensure that when these girls become women and have children, neither they nor their babies fall prey to undernutrition. It’s a preventative strike on the double burden: healthy girl today, healthy mother tomorrow, healthy baby the day after.

In summary, Smile Foundation’s work on nutrition is comprehensive, addressing immediate undernutrition while also promoting long-term healthy habits. They’re essentially performing “double-duty actions,” a term used by experts to describe interventions that address multiple forms of malnutrition at once. For example, feeding a child at school (addresses undernutrition) and educating that child about healthy foods (helps prevent obesity later) is a double-duty action. Distributing iron tablets (treats micronutrient deficiency) and teaching a community to grow spinach (provides sustainable source of iron) is another double-duty move. By complementing government schemes like the public food distribution, mid-day meals or the Anaemia Mukt Bharat (Aanemia-Free India) campaign with these community-driven efforts, Smile Foundation ensures that policies on paper translate to food on plates and knowledge in minds.

It’s not just about giving out food but about changing behaviour and systems. And sometimes, it’s about making nutrition fun – be it through a local recipe contest or a celebrity cook-off – so that people want to be a part of it. After all, fighting malnutrition is serious, but it doesn’t all have to be grim. A dash of humour or a community celebration can make people more receptive, whether it’s kids learning through a puppet show that vegetables are heroes or moms laughing in a workshop as they learn how to sneak pumpkin into parathas (flatbread) to up the vitamin A content.

Success stories: From Plates Half Empty to Plates Half Full

No article on this topic would be complete without a few inspiring stories of change. We’ve already met Kiran, the little girl who went from eating mud to enjoying hearty school meals and thriving. But there are many Kirans and countless more subtle transformations happening every day through sustained efforts.

Take the case of a village in Banaskantha, Gujarat, where adolescent girls used to commonly faint in school due to anaemia. Before Smile Foundation intervened, a whopping 78% of girls aged 14–19 were anaemic in that region (far above the national average). These girls started receiving the special laddoos, nutrition classes and supplements. One of the beneficiaries, let’s call her Rekha, shared in a community meeting that earlier she felt tired just walking to school, but after a few months on the programme, she could concentrate in class and even convinced her mother to cook the family’s lentil soup with the greens from their kitchen garden – a habit they learned in the programme. Over 70% of the girls improved their health status and they carried those lessons home, turning it into a family and community improvement.

Or consider Sangrur, Punjab, where the Nutrition Enhancement Programme mentioned earlier turned things around dramatically in 23 villages. Here, a school principal noticed that ever since the kitchen garden produce (like spinach and fenugreek) started appearing in school lunches and children were taking iron syrup mixed in meals, absenteeism dropped. Kids weren’t falling sick as often. One mother commented (half in jest) that her son used to hate green veggies but once he learned in the school sessions that “Popeye was strong because of spinach,” he started eating it thinking he’ll get muscles! It may sound funny, but such creative education made kids eat better, which made them healthier. In just six months, anaemia in some schools nearly vanished. It’s almost like a magic trick but backed by very real science and a lot of hard work on the ground.

In Mathura, Uttar Pradesh, the “Pink Smile” project (in partnership with a corporate donor) set up regular health camps in 10 villages. A local health worker, Sunita, recounts how they discovered dozens of women with moderate anaemia who had never been diagnosed. “They just thought it’s normal to feel dizzy and look pale,” Sunita said. After enrolment in Pink Smile, these women got treatment and learned simple diet tweaks (like adding a handful of leafy greens to their daily curry). A few months later, many of these women reported higher energy levels. One woman even said she finally had the strength to start a small tailoring business from home now that she wasn’t constantly fatigued. Empowerment can start with something as basic as not being anaemic.

Battling malnutrition is about enabling people to live their lives to the fullest. A well-nourished child can focus in class, play and dream of a better future. A well-nourished teenager can pursue skills and opportunities instead of being held back by illness. A well-nourished mother can earn, care and contribute to her family without the drag of constant weakness. In short, nutrition is the foundation upon which individuals and communities build better lives.

Poshan Maah 2025: From double burden to double victory

Addressing the double burden of malnutrition may sound like chasing two rabbits at once. But the truth is, the solutions for undernutrition and overnutrition are two sides of the same coin: ensure everyone has access to balanced, nutritious food and the knowledge to choose healthy lifestyles. It’s not as out-of-reach as it seems, especially with the spirit of Poshan Maah 2025 around. Here are a few broad strokes of what’s needed (and happening) to turn this double burden into an opportunity for double victory:

- “Double-Duty” policies: Governments and organisations are increasingly adopting double-duty actions, meaning strategies that tackle both ends of malnutrition simultaneously. For example, fortifying staple foods with vitamins (like adding iron to flour or vitamin A to cooking oil) can help undernourished populations and ensure those who eat a lot of these staples don’t become micronutrient deficient. School meal programmes now often emphasise not just giving calories but giving diverse food (protein, veggies, etc.) to prevent undernutrition and obesity. Nutrition programmes are aligning with agriculture to promote crops that are climate-resilient and nutrient-rich, so communities don’t resort to just rice or wheat but have millets, legumes, fruits, etc. readily available. The idea is to end undernutrition without inviting obesity – growth without the growing pains.

- Education and behaviour change: Perhaps the most powerful tool is knowledge. When a community understands nutrition – truly grasps why a carrot is better than a candy – they become active participants in their health. This is where Smile Foundation’s model can be replicated and scaled. Imagine every village having a nutrition champion or every school including basic nutrition in the curriculum. It sounds mundane, but these are lifelong lessons. Kids who learn to snack on fruit instead of fried chips carry that habit into adulthood and to their own kids. Many countries are now running public health campaigns about the dangers of sugary drinks and ultra-processed foods (some with humorous jingles because who doesn’t remember a funny ad?). Empowered consumers will demand healthier options and make better choices cutting off malnutrition at both ends.

- Strengthening health systems: Early detection is key. A child shouldn’t have to become severely wasted or an adolescent morbidly obese before action is taken. Training health workers to monitor growth, check for anaemia, counsel on diet – all these make the healthcare system a frontline fighter against malnutrition. Initiatives like India’s Poshan Abhiyaan (National Nutrition Mission) are using technology (smartphone apps for health workers) to track every child’s nutrition status. If something is off, interventions kick in sooner. It’s much easier to course-correct early – give a malnourished toddler supplemental food before stunting becomes irreversible or advise an overweight teen before they develop diabetes. Health systems also need to treat malnutrition in all its forms as part of routine care (e.g., diabetes clinics that also screen for undernutrition and vice versa). A holistic approach means whether someone comes to a clinic for weight loss or weight gain, they get guided towards balance.

- Community engagement and empowerment: As the Smile Foundation experience shows, involving the community creates lasting change. Women’s self-help groups learning about nutrition, youth clubs doing healthy cooking competitions, local leaders being nutrition advocates – these social approaches make good nutrition a community value. In places where malnutrition was once accepted as “fate” or simply not noticed, community-led monitoring can spur action. For example, villagers in some areas have started their own nutrition kitchens or co-ops to ensure everyone gets at least one nutritious meal. When communities are empowered, they also hold governments accountable ensuring food programs are delivered, demanding clean water and sanitation (which are critical to prevent disease-related undernutrition) and so on. Think of it as crowd-sourcing good health.

- A touch of innovation: The fight against malnutrition is also getting innovative. From bio-fortified crops (like zinc-enriched wheat) to mobile apps that teach mothers recipes, the arsenal is growing. Even the humour and creativity seen in campaigns like cartoons explaining the food plate or the use of local comedians to spread messages are forms of innovation. Chef Vikas Khanna’s healthy laddoo is a small innovation that paid off big. There are also policy innovations like taxes on sugary drinks (to reduce consumption) and subsidies on fruits and veggies (to encourage healthy eating). Each context will require a tailored mix of these innovations, but the encouraging part is that we humans are quite resourceful when we recognise a problem and malnutrition in all its forms is finally being recognised as a problem that every country must address.

In closing, it’s worth reminding ourselves why all this matters. Combating the double burden of malnutrition isn’t just a numbers game or a box to tick for the Sustainable Development Goals. It’s about people – the child who can grow tall and smart because she got the right nutrition, the mother who survives childbirth and raises a healthy family because she overcame anaemia, the community that thrives because its members are strong and productive, not held back by illness. There’s a saying that “a healthy mind in a healthy body” is the key to a happy life. We need to create conditions for both minds and bodies to be healthy which means ending undernutrition and promoting healthy eating.

The double burden of malnutrition might seem like a daunting double villain. But with integrated efforts, it can be defeated with a double dose of common sense and compassion. One part is ensuring food security – no one should go to bed hungry or wake up unsure of their next meal. The other is ensuring nutrition security – that people’s diets actually contain the nutrients needed for a healthy life, not just any calories. Organisations like Smile Foundation exemplify this dual approach by filling plates and educating palates at the same time. As we often emphasise, food is a basic necessity and proper nutrition is a fundamental right. When we help fulfil that right, we’re not only saving lives – we’re also adding joy and productivity to those lives, empowering the next generation and building a healthier nation and world.

So, whether you’re a policymaker, a donor, a health professional or a concerned member of the general public, remember that solving malnutrition is everyone’s cup of (fortified) tea. It can be as simple as supporting a school meal programme, spreading the word about healthy eating or contributing to NGOs like Smile Foundation that are on the frontlines. The burden may be double, but so can be our resolve. With a bit of teamwork – and perhaps a healthy laddoo in hand – we can ensure every child and adult has the right kind of weight on their shoulders (like the weight of a schoolbag or a bright future) and not the weight of malnutrition. And that outcome would truly be something to smile about.

Where Poshan Maah 2025 fits in

Every September, India observes Poshan Maah – a campaign to improve nutrition awareness, promote healthy practices and encourage community action. Poshan Maah 2025 is particularly relevant because it stresses convergence: linking food security, health, sanitation and education to fight malnutrition in all its forms. That aligns perfectly with Smile Foundation’s approach. Whether through daily meals at Mission Education centres, kitchen gardens for families or anaemia screening for adolescent girls, Smile’s interventions are real-life examples of how awareness plus action can turn the tide against both undernutrition and obesity.

So, while Poshan Maah provides the annual rallying cry, organizations like us ensure the momentum carries on all year. Together, they help India tackle malnutrition not just in headlines, but in households.

Sources:

- WHO Fact Sheet on Malnutrition (2024) – key global stats on undernutrition and obesity

- Smile Foundation Blog – “Let’s Fight Malnutrition in Children Together” (2019)

- Smile Foundation Blog – “Nutrition support for better learning outcomes” – Kiran’s story of improved health through daily school meals

- Scientific Reports (2023) – Study on India’s double burden (NFHS-5 data: 24% women overweight; ~7% mother-child pairs facing DBM)

- Smile Foundation Press Release (2019) – Chef Vikas Khanna’s nutritious laddoo initiative, with 70% of 1,000 girls improving hemoglobin & BMI

- WHO EMRO – Definition of double burden of malnutrition (coexistence of undernutrition with overweight/obesity or diet-related NCDs).

- Smile Foundation Blog – “Focus on Nutrition, Not Hunger” (2023) – discusses importance of balanced diets vs just filling stomachs

- Additional data from WHO and research articles on the need for double-duty actions in nutrition policy