On a humid June morning in rural Bihar, 32-year-old Sunita Devi (name changed) cycles seven kilometres to reach the first home on her list. She’s the only Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) for five villages, tasked with everything from checking on expectant mothers to persuading families to vaccinate their children. By mid-morning, she’s rushing to an Anganwadi centre — a one-room space without electricity — to coordinate nutrition for toddlers. She does this six days a week. For her labour, she takes home a base honorarium of ₹2,000 a month from the central government, topped up by small, task-based incentives. There’s no paid leave, no retirement plan, no health insurance.

Yet without Sunita and millions like her, India’s public health and nutrition system — especially in rural areas — would collapse.

India’s first responders, without the recognition

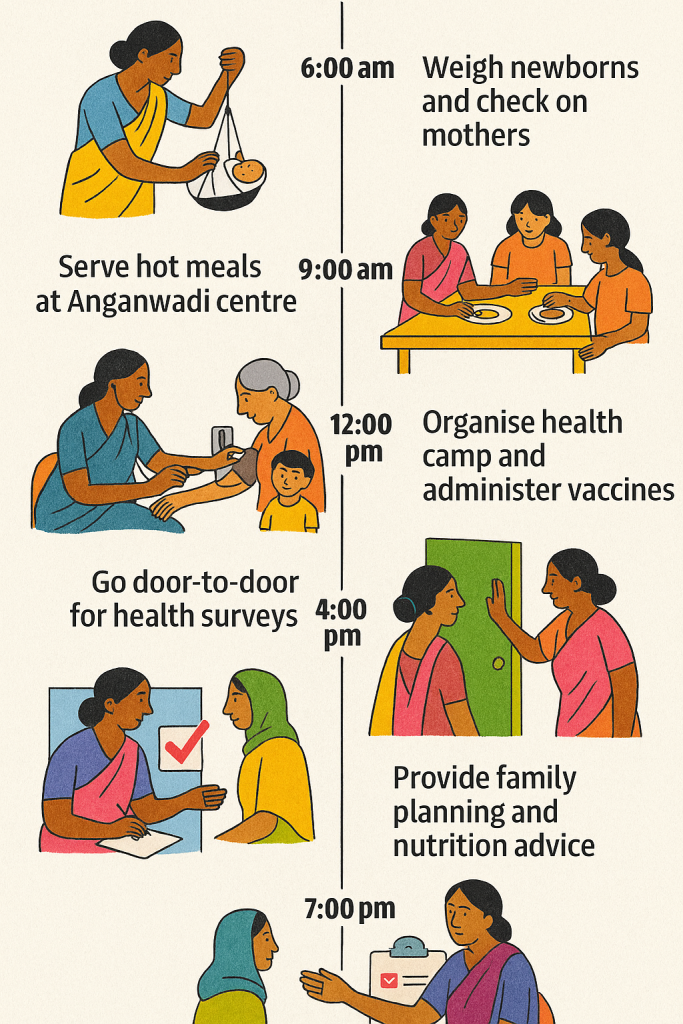

India’s ASHA programme, launched in 2005 under the National Rural Health Mission, is the world’s largest volunteer health workforce. As of June 2022, more than 1.05 million ASHAs were serving across the country. In the remotest hamlets, they are often the first and only point of contact with the formal health system. Their roles span maternal care, facilitating institutional births, ensuring immunisation, promoting hygiene, distributing medicines and contraceptives, and sometimes handling emergencies with little more than determination and community trust.

But the work is relentless: 8–12 hours a day, often without protective gear, without job security and with pay that would barely cover a week’s groceries in a city. The model relies on a gendered and caste-based assumption — that care is “natural” for women, and therefore doesn’t deserve the wages or protections of “real” work.

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed this contradiction. ASHAs became frontline warriors — delivering medicine, raising awareness, tracking cases, escorting patients to hospitals. Many contracted the virus; hundreds died. A few states paid token bonuses. For most, their status as “volunteers” meant no compensation to their families.

The Parallel Pillar of public health: Anganwadi workers

Alongside ASHAs are Anganwadi workers — the educators, caregivers and nutrition providers for millions of children under six and their mothers. India’s 13.9 lakh Anganwadi centres (AWCs) operate under the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) scheme, offering early childhood care, meals, health check-ups and preschool education.

But here too, systemic neglect is rife. According to Poshan Tracker data from June 2025, 10,868 AWCs across the country functioned for less than 20% of working days in that month — mostly in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Arunachal Pradesh and Manipur. That’s an improvement from June 2024, when nearly 30,000 centres failed to open regularly, but it’s still unacceptable for a service that underpins early childhood development.

The disparities are stark: Delhi, Goa and Chandigarh report almost full functionality, while large rural states struggle to keep doors open. The reasons range from inadequate infrastructure to chronic underfunding, to workers juggling multiple roles without support. In many villages, Anganwadi centres operate in borrowed spaces with no toilets, unsafe drinking water, no play materials and no storage for food.

The costs of public health neglect

The economic argument for investing in these frontline systems is unassailable. Neglecting them means higher maternal and infant mortality, greater malnutrition, more children starting school at a disadvantage and heavier long-term burdens on the healthcare system.

The social costs are just as severe. These centres are often the only spaces where rural women can gather, learn and exercise leadership. When they decay, so does the community’s sense of collective welfare. The undervaluation of ASHAs and Anganwadi workers is part of a broader, global pattern in which women’s unpaid or underpaid care labour props up entire economies — while remaining invisible in national accounts.

What needs fixing — Now

The fixes aren’t rocket science, but they require political will.

- Recognise their work as work

ASHAs must be recognised as part of India’s formal health workforce, with salaries that reflect their essential role. Calling them “volunteers” while expecting them to deliver professional-level outcomes is unjust and unsustainable. Anganwadi workers should have structured pay scales, pensions and benefits. - Upgrade infrastructure

Every Anganwadi centre needs a permanent, safe building with electricity, clean water, functional toilets and space for learning and play. ASHAs need secure transport, basic equipment and facilities for their community health duties. - Capacity building

Ongoing training is critical — whether for using digital tools, counselling on nutrition, tracking child growth or managing emergencies. Better-trained workers produce better health outcomes and training has a proven multiplier effect on community resilience. - Protective gear and safety protocols

COVID-19 made clear the dangers of leaving frontline workers unprotected. Gloves, masks, sanitisers and first-aid kits should be non-negotiable basics. - Mental health and grievance redressal

These jobs are emotionally and physically taxing. Support systems, peer groups and accessible complaint mechanisms must be institutionalised.

Proof that targeted interventions work in public health

Smile Foundation offers a glimpse of what’s possible when investment meets intent. Working with corporate partners like PepsiCo and Mars Wrigley, we have strengthened Anganwadi capacity and supported ASHA networks in multiple states.

- Punjab: The Nutrition Enhancement Programme improved maternal and child nutrition for over 60,000 people. Initiatives included kitchen gardens, 260 health camps and skills training for Anganwadi workers.

- Maharashtra: Upgrades to 13 Anganwadi centres brought solar lighting, toilets, furniture and water filters — directly benefiting nearly 5,000 people.

- Mathura, Uttar Pradesh: The Pink Smile initiative delivered anaemia screening and treatment to over 4,000 women and children via mobile medical units.

These projects are modest in budget compared to mega-infrastructure schemes, yet their impact is profound and immediate.

The global context

Globally, frontline community health workers are increasingly recognised as cost-effective public health investments. Studies in sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America show that every dollar spent on community health yields multiple dollars in economic benefits through improved productivity, reduced disease burden and higher educational attainment.

India’s demographic and geographic scale means it stands to gain even more — but only if these roles are professionalised, funded and supported. Otherwise, the cycle of underinvestment and attrition will continue, weakening the country’s human development indicators.

A matter of justice

This is not just about efficiency. It’s about justice. India’s ASHAs and Anganwadi workers are overwhelmingly women from marginalised backgrounds. They navigate gender discrimination, caste hierarchies and bureaucratic indifference — yet remain the face of the state in millions of homes. They are the ones who knock on doors, carry vaccine coolers in the heat, comfort sick children and weigh newborns on hanging scales.

To continue exploiting their labour without recognition or protection is to betray the very principles of equity and dignity that the public health system claims to uphold.

The smartest investment India can make for public health

In the coming years, India will spend billions on new hospitals, AI health platforms and biomedical research. All of that will be undermined if the base of the pyramid remains fragile. Strengthening ASHA and Anganwadi capacities is the smartest, most cost-effective public health investment India can make. It builds healthier mothers, stronger children and more resilient communities.

The question is not whether we can afford to pay them fairly and equip them properly. The question is whether we can afford not to.