Where do women stand in India’s social and political landscape today? The answer is a story of both inspiring progress and ongoing struggle. For generations, Indian women have fought to claim their space in society – from legendary freedom fighters in the Independence movement to modern lawmakers shaping the nation.

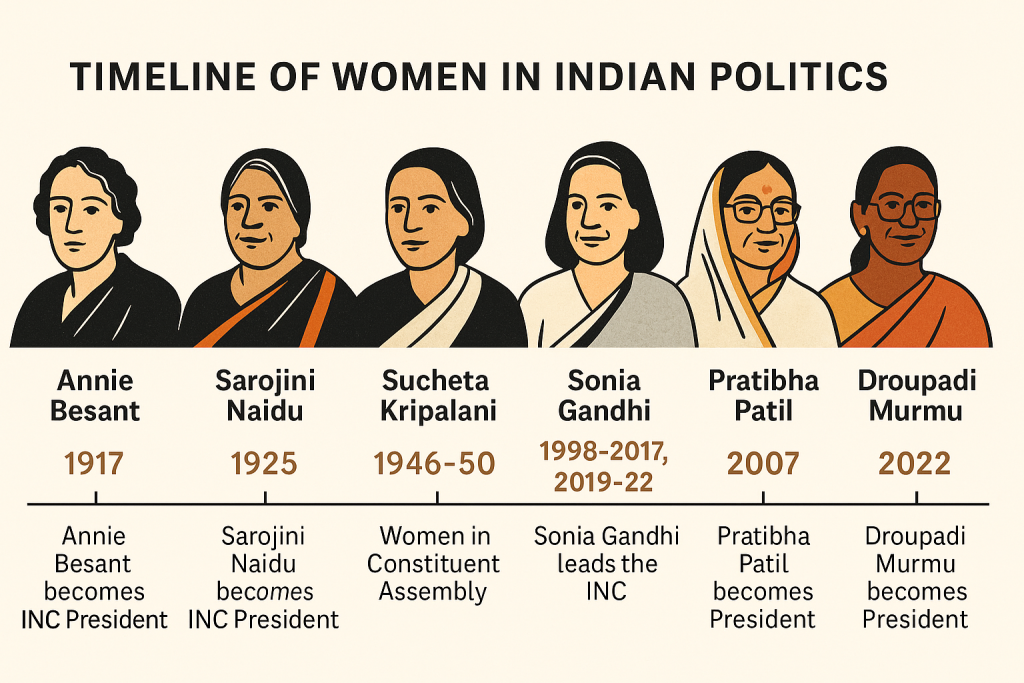

A legacy of women leaders in Indian politics

When we look back, women’s participation in Indian politics is anything but static – it’s been a dynamic force growing stronger each decade. Even during the freedom struggle against British colonialism, women played crucial roles: from Sarojini Naidu raising her voice for equality to the fierce leadership of Sucheta Kripalani and Aruna Asaf Ali. These trailblazers proved that women’s leadership was integral to India’s destiny. After independence, India broke global norms by granting universal suffrage to women and men alike from the very first election – a historic step that many Western democracies took decades to achieve. In fact, it was only in 1950 – with the birth of the Republic of India – that all women in India finally won the unconditional right to vote. This early commitment set the stage for women to enter public life as equals in principle, if not always in practice.

Over the years, women have risen to some of the highest offices in the country, shattering glass ceilings that once seemed impenetrable. India was one of the first nations in the world to elect a woman Prime Minister – Indira Gandhi took office in 1966, showing that a woman could lead the world’s largest democracy. Since then, we’ve seen women become Presidents (like Pratibha Patil), powerful Chief Ministers (from Jayalalithaa to Mamata Banerjee) and influential opposition leaders.

At the grassroots too, change was set in motion by progressive policies: the 73rd Constitutional Amendment (1992) reserved one-third of seats in village panchayats for women, a quota later increased to 50% in many states. This means millions of women in rural India have had a chance to serve as village council heads (sarpanchs) and local representatives. From village councils to Parliament, more women than ever before are stepping into leadership roles, determined to shape their communities and country.

Yet alongside these shining examples, the reality for most Indian women remains a mix of advancement and adversity. Today, far more girls attend school and university than in previous generations, and many more women join the workforce and community leadership roles than before. The very sight of women gathering in village meetings or contesting elections – once a rarity – is gradually becoming commonplace. Women in India continue to raise their voices for equal rights and social change, whether on the streets in protest or within the halls of policymaking. But despite this active participation, deep-rooted challenges persist and the journey toward true equality is far from over.

Women representatives participate in a local governance meeting in India, highlighting the growing (if still limited) presence of women in grassroots politics. Over the decades, the numbers tell a story of both progress and disparity. Indian women have proven their resolve by increasingly exercising their right to vote and contest office, but they still struggle to secure a fair share of actual power. In the following sections, we’ll dig into the data on women’s political participation, examine the barriers that continue to hold women back and explore the efforts – from legal reforms to grassroots initiatives – that aim to bridge the gender gap in Indian politics.

By the numbers: Women’s political participation today

In recent years, data shows that women’s political participation in India has been steadily rising, even if representation in power remains skewed. Consider the act of voting – the most fundamental expression of democracy. Women’s voter turnout has climbed dramatically since the early decades of independence. In 1962, only about 46.6% of eligible women cast their ballots, reflecting both social barriers and an enduring gender gap. Fast forward to the latest national election in 2024 and nearly 65.8% of women voters turned out to vote. This surge in female voter participation signifies an important cultural shift.

In fact, the once-wide turnout gap between men and women has virtually evaporated. For the first time in India’s history, women matched or even slightly surpassed men in voting rates in the 2010s – notably in 2019, female voter turnout actually exceeded male turnout (women made up roughly 49.5% of voters that year). Indian women, even in rural and traditionally conservative areas, are increasingly claiming their political voice at the ballot box, often outnumbering men in polling booths and defying anyone who doubts their commitment to democracy.

This growing assertiveness isn’t limited to voting. More women are also stepping forward to contest elections – to not just vote for leaders, but to be the leaders. The change from the past is striking. Back in 1957 (India’s second general election), only 45 women in the entire country ran as candidates for Parliament. At that time, seeing a woman’s name on the ballot was like spotting a unicorn. Fast forward to the 17th and 18th Lok Sabha elections in 2019 and 2024 and the number of women candidates swelled into the hundreds.

In the 2024 general election, 797 women candidates entered the fray out of 8,337 total candidates. That’s a seventeen-fold increase in women’s participation as candidates since the 1950s. It’s an encouraging sign that more women want to run for office and serve, even if many face an uphill battle in the male-dominated arena of electoral politics. For context, women’s share among all candidates was about 9.5% in 2024 – a slight rise from 9% in 2019. Clearly, political parties are still overwhelmingly fielding men, but the needle is slowly moving as women push into these spaces.

Now, how about representation in the legislatures – the people who actually win and hold office? Here too, the trend is upward, though the pace has been agonisingly slow. In 1952, women made up just about 5% of the Lok Sabha, India’s lower house of Parliament. Only 22 women were elected in that first Lok Sabha of independent India, out of 489 MPs. Fast forward over 70 years: in the current Lok Sabha (elected in 2024, the 18th Lok Sabha), 74 women MPs were elected, comprising 13.6% of the house. This is the highest number of women Parliament has ever seen – yet it’s still only one out of every seven MPs.

In fact, women’s representation dipped slightly in 2024 compared to 2019 (when there were 78 women MPs, about 14.4%), reminding us that progress is not always linear. The upper house, Rajya Sabha, has seen a similar gradual rise – from roughly 7% women in the 1950s to about 13% in 2023. These figures underscore a sobering reality: even in 2025, Indian women are vastly underrepresented in the highest corridors of power. A country that had a woman Prime Minister over fifty years ago still hasn’t cracked the code to gender balance in its Parliament.

At the state level and local levels, however, there are some bright spots. Several state assemblies have seen increases in women MLAs (Members of Legislative Assembly), though none have anywhere near parity. But it’s at the level of local governance – the panchayats and municipalities – where India has made a quantum leap, thanks to constitutional quotas. Today, women form almost half of all local government representatives. As of 2023, about 46.6% of the 3.23 million panchayat representatives are women. That’s roughly 1.5 million women leading village councils, sitting in block committees and making decisions for their communities. This is a stunning transformation from a few decades ago when village leadership was almost entirely male.

In many local bodies, reserved seats for women have normalised the presence of sarpanchnis (women village heads) and council members – creating a pipeline of experienced female leaders at the grassroots. In 2022, women made up about 44% of local government representatives nationwide and that share has only grown. This means the face of local governance in India is increasingly female, which could, over time, change attitudes about women in leadership and create bottom-up pressure for greater representation in higher offices.

The data points to an optimistic conclusion: women in India are more politically engaged than ever before – they are voting in massive numbers, contesting elections in greater frequency and gradually winning more positions of power. Each percentage gain represents millions of women’s voices being heard. However, numbers alone don’t tell the full story. A rising graph of participation doesn’t automatically equal real empowerment. To truly understand where women stand in India’s socio-political spaces, we must also confront the harder question: what obstacles are women still facing, and why – despite greater participation – do they remain so underrepresented in actual decision-making? The next section delves into these challenges.

The gender gap and ongoing challenges

For all the gains women have made, stark gender gaps and deep-rooted barriers continue to define their political journey – in India, as in much of the world. It’s a bitter truth that while women make up nearly half of India’s population and voters, they occupy only a small fraction of its power structures.

Globally, women remain underrepresented at all levels of decision-making and India is no exception. According to the World Economic Forum’s latest analysis, at the current rate of progress it will take an estimated 123 years to achieve full gender parity worldwide. (This bleak figure is actually an improvement – it was 132 years as of 2024, so the world inched 9 years closer in the past year.) Still, 123 years is far too long to wait for equal representation. And for many Indian women, the pace of change feels glacial, especially when their daily reality includes discrimination, safety concerns and unequal access to resources.

Let’s talk about Indian politics on the ground – a realm still dominated by men, where women who dare to enter often face hostility or condescension. One major challenge is sheer cultural inertia and patriarchal attitudes. For decades, politics was seen as a “man’s domain,” and vestiges of that mindset linger. Female politicians frequently have to work twice as hard to be taken seriously. They are subjected to sexist remarks, their competence questioned, their private lives scrutinised.

The idea of a woman wielding authority can provoke backlash in a society where many still expect women to be deferential. The system wasn’t built with women in mind and sometimes it shows its teeth to those trying to change it. Indeed, women who speak up or step out of “their place” often face disproportionate criticism and even abuse. It’s not uncommon to see outspoken women leaders being trolled on social media or heckled in legislatures with misogynistic jibes. This toxic environment can discourage women from pursuing public life – yet many persist, fuelled by a desire to change the very system that marginalises them.

One of the most pernicious manifestations of patriarchy in Indian politics is the phenomenon of “proxy women” or Pradhan Pati (literally, “husband of the chief”). This refers to situations – particularly in rural local bodies – where a woman is elected to a position (often due to a reserved seat), but the real power is wielded by her husband or a male relative.

In some village councils, the elected woman sarpanch is essentially a figurehead while her husband (jokingly dubbed the sarpanch pati) sits in on meetings, makes decisions, and signs documents on her behalf. It’s the oldest trick in the patriarchy playbook: satisfy the letter of women’s reservation laws by installing a woman in the seat, but preserve male control behind the scenes. This “proxy politics” undermines the very purpose of empowering women through reservations and unfortunately it’s widespread in certain areas.

As one government report noted, women constitute nearly 46% of panchayat representatives, “however, their effective participation remains low, especially in northern states like Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Haryana, and Rajasthan, where male relatives often control decision-making”. The term Pradhan Pati has entered the political lexicon to name and shame this practice. It highlights how deeply entrenched gender norms can subvert progressive laws – families and communities may feel uncomfortable with women in power, so they enforce the old norms by propping up the men in the shadows.

Women serving in local office often face immense pressure from family and community to act as rubber stamps. Interference by husbands or male kin not only robs women of agency but also robs the community of genuine female leadership. As a result, many women representatives struggle to exercise their authority. They are talked over in meetings, excluded from important discussions or simply ordered by their family on how to vote or govern. It’s common to hear anecdotes of a villager approaching the husband of a woman pradhan to get things done – because everyone “knows” he’s the real boss. This is profoundly disempowering for women who genuinely want to lead. It also shows that changing laws (like introducing quotas) is not enough on its own; social attitudes have to evolve so that a woman leader is respected in her own right.

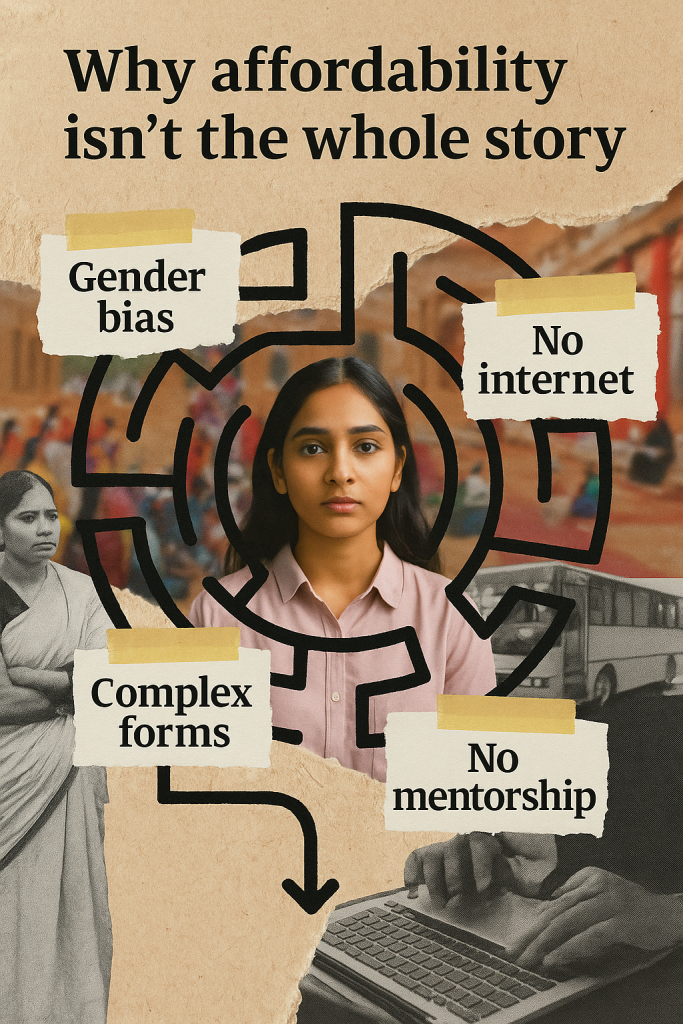

Additionally, lack of support and resources holds many women back. Politics is a game that often runs on money, connections and the old boys’ network. Women, who historically have had less access to financial resources and public networks, find it harder to fund their campaigns or connect to mentors. Political parties – the gatekeepers of electoral tickets – often hesitate to nominate women in winnable seats. Some party leaders still harbour biases that women are “weak candidates” or won’t be able to handle the rough-and-tumble of electoral combat. This results in women being passed over for party tickets or being fielded in unwinnable constituencies as token candidates.

The old prejudiced question, “Can she win?” still hangs over women aspirants, even when data shows women legislators perform as well or better than their male counterparts when given a chance. There’s also a networking gap – many male politicians groom their sons or younger male colleagues to succeed them, whereas women often lack similar patronage. The absence of adequate support systems – from funding to security to mentorship – means women entering politics must often blaze a trail on their own.

Another harsh reality: violence and safety concerns. Politics in some parts of India can be violent and women candidates have faced harassment, threats and even physical assault. In areas with intense political rivalries, a woman canvassing door-to-door might fear for her safety in ways her male colleagues don’t. Online violence is another modern scourge – women in public life are routinely subjected to trolling, abuse and threats on social media, with attacks often targeting their gender or personal life. This creates a chilling effect, as some women decide the mental toll of a public role is simply too high.

Finally, the double burden of domestic responsibilities cannot be ignored. Society still largely expects women to be primary caregivers and homemakers. Thus, a woman in politics often juggles multiple roles – managing her household and children alongside a demanding public career. The long hours and travel that political life entails can strain family life, and without supportive partners or infrastructure (like childcare), many women simply cannot afford to devote themselves fully to politics. It’s a classic Catch-22: we need more women in leadership to push for policies (like childcare, flexible work, parental leave) that would help ease these burdens, but the burdens themselves make it harder for women to ascend to leadership.

One might imagine the everyday heroism of women who persist despite these challenges: the young woman sarpanch who studies government manuals at night because her husband never lets her speak in meetings; the female MP who endures jeers in Parliament with steely grace; the first-time candidate who campaigns with a baby on her hip because she has no alternative. These stories exemplify both the resilience of Indian women and the unfair weight placed upon them.

The Indian government and civil society are aware of many of these issues, and there have been efforts to address them. For instance, a government panel in 2023 recommended “exemplary penalties” for those caught engaging in proxy leadership, to crack down on the Pradhan Pati culture. They suggested measures like publicly swearing in women leaders in open village assemblies (to affirm that she holds the office), appointing women-only ombudspersons to hear complaints and even creating support networks and training for elected women. The logic is clear: it’s not enough to reserve seats for women; we must ensure women can actually exercise the power of those seats.

Similarly, activists and NGOs are conducting leadership workshops for women in local government, teaching them about their legal powers, budgeting and public speaking, and crucially, how to push back when someone tries to usurp their role. These efforts, though on a modest scale, are vital sparks of change.

The United Nations and other international bodies have also emphasised the importance of women’s equal participation. UN Women has repeatedly stated that women’s underrepresentation in decision-making is a loss for society and achieving gender parity in political life is a prerequisite for true democracy and sustainable development.

The World Economic Forum’s Gender Gap Report ranks countries on political empowerment – and India currently ranks low (in 2023, India was 127th out of 146 countries on overall gender gap, with particularly poor scores in political representation). This is a reminder that India, despite being the world’s largest democracy, has much work to do to ensure that its democracy is inclusive of all its citizens.

In summary, women in India stand at a crossroads of change. They have made significant strides in participation and visibility, yet they continue to battle systemic sexism and structural barriers that men do not face. The gender gap in politics is about power, attitude and culture. Bridging it requires a transformation in how we as a society view women as leaders.

Pushing forward: Reforms and the road ahead

The challenges are steep, but they are not insurmountable. History shows that change is possible when pushed by collective will and bold reforms. To truly elevate women’s position in India’s political sphere, a multi-pronged approach is needed – combining legal mandates, institutional reforms and social initiatives. This means tackling the problem at all levels: from Parliament down to the village and from political parties to households.

A critical step that has long been discussed, and finally saw a breakthrough, is the idea of reservations (quotas) for women in state and national legislatures. For decades, activists and progressive politicians campaigned for a Women’s Reservation Bill that would reserve 33% of seats in the Lok Sabha and State Assemblies for women (similar to the quota in panchayats). After many false starts, this historic reform was passed by Parliament in 2023. The Constitution (106th Amendment) Act, 2023 – often hailed as the Nari Shakti Vandan Adhiniyam – became law, aiming to ensure that one-third of all seats in the national and state legislatures will be earmarked for women. If implemented, it could swiftly raise women’s representation in the Lok Sabha from the current ~14% to at least 33% – the biggest leap in history. It’s as if the political map of India is being redrawn with women at the centre.

However, the bill comes with its own caveats and timeline (its provisions will be enacted after the next delimitation of constituencies, which means it may not take effect until a future general election, possibly 2029). The journey from 13.6% to 33% representation will still take time and political will to realise. Activists are urging that the implementation be expedited and not lost in procedural delays. Passing a law is only half the battle; enforcing it is the next. Still, the very passage of the Women’s Reservation Bill marks a paradigm shift. It’s an official acknowledgment that extraordinary measures are required to correct the historical imbalance.

It is turning the slow drip of progress into a fire hose – forcing open the gates for women to enter en masse into decision-making roles. If one out of every three lawmakers in India is a woman in the near future, it could profoundly change not just legislation on women’s issues, but the very culture of policy-making (potentially making it more collaborative and inclusive, as some studies suggest happens with more women at the table).

Yet, quotas alone won’t solve everything. Political empowerment must be accompanied by social, economic and cultural empowerment. There’s a saying: “Give a woman a seat at the table and then watch to ensure she isn’t on the menu.” Women who enter politics need an environment that allows them to thrive and lead effectively. This is where capacity-building and support systems become crucial. We need robust programmes to train and mentor aspiring women leaders.

Imagine leadership development workshops across the country, where experienced women politicians and professionals coach younger women in public speaking, navigating party structures, crafting policy and running effective campaigns. Some of this is already happening in pockets – for instance, the government committee on Panchayati Raj recommended creating federations of women panchayat leaders for peer support and partnering with educational institutions to provide leadership training for women in local office.

Similarly, civil society organisations are running “campaign schools” for women, teaching them practical skills like filing nominations, fundraising and using social media for outreach. Expanding these training programmes nationally could massively boost women’s confidence and competence in the political arena. When a woman knows her stuff – knows the rules, the procedures, the tricks of the trade – it’s much harder for others to sideline her.

Mentorship is another key. Every successful person in politics often has a mentor or a guide. Creating mentorship networks that pair young female political aspirants with seasoned women leaders can help transfer knowledge and create solidarity. Senior women who have broken barriers can lend a hand to the next generation, advising them on handling both policy issues and bias they will inevitably face.

In an ideal scenario, each political party would have a structured mentorship and training wing for women – identifying promising talent at the grassroots and grooming them for larger roles. This is not wishful thinking; some parties have started women’s wings and leadership programs, but these efforts need to be more than symbolic. Parties must also walk the talk when it comes to candidate selection. One concrete ask from activists is for parties to voluntarily field women in at least 33% of the constituencies, even before the reservation law compels them to. This means winnable seats, not just token contests.

A few parties in recent state elections have indeed given 40–50% tickets to women (with notable success – women candidates often have a higher win ratio). It’s time this becomes the norm, not the exception, across the political spectrum. Voters, too, can play a role by demanding their parties put forward more women and by supporting women candidates at the polls.

Another area of focus should be strengthening laws and mechanisms to ensure women’s safety and dignity in politics. This includes stricter action against those who harass or assault female candidates and better enforcement of codes of conduct to prevent sexist hate speech during campaigns. The Election Commission of India could consider guidelines to rein in candidates who make misogynistic comments or attempts to intimidate women opponents.

On the logistical side, providing facilities like childcare or flexible meeting times can make it easier for women (especially young mothers) to participate in politics. Some local bodies have experimented with creches at panchayat meeting venues – small steps like these send a powerful message that women are welcome and accommodated in these spaces, not just reluctantly tolerated.

Education and awareness campaigns at the community level are also vital. If a village’s elders understand that a woman sarpanch has the same authority as any man, they might be less likely to default to the husband for decisions. Public campaigns to celebrate women leaders or community dialogues about the value of women’s leadership, can slowly chip away at societal biases. The media, too, has a role: representation of women politicians in media should move beyond focusing on what they wear or their family background and instead highlight their work and impact. Visible success stories of women leaders can inspire others and change perceptions.

The road ahead requires a coalition of stakeholders – government, civil society, communities and women themselves – pushing together. It means not just top-down reforms, but bottom-up societal change. Revolutions don’t happen by waiting politely; they happen by persistent pressure and rebellious hope. Indian women and their allies must keep the pressure on – to implement the reservation law quickly, to hold parties accountable, and to challenge sexist norms wherever they see them. Each barrier knocked down creates momentum for the next.

Women as agents of change

Amid these systemic efforts, it’s important to remember that women are not just beneficiaries of change – they are often the drivers of change themselves. Across the globe and in India, women have proven themselves indispensable agents of change, activism and social transformation. Whenever society has moved forward – whether in movements against colonialism, fights for civil rights or struggles for environmental justice – women have been on the frontlines, leading with courage and compassion. They have organised communities, challenged oppressive systems and advocated for the marginalised.

In India, think of the Chipko movement in the 1970s where village women literally hugged trees to prevent deforestation or the anti-liquor agitations led by women that spurred social reform in states like Andhra Pradesh. From grassroot activism to policy innovation, women’s contributions have been game-changing. They bring perspectives that prioritise community well-being, inclusivity and long-term thinking – qualities the world desperately needs in leadership.

Women activists and leaders also often embed storytelling in their approach to change. They use the power of personal narrative and empathy to rally others. Whether it’s a mother advocating for better sanitation in her village by recounting how lack of toilets affected her daughters or a young parliamentarian sharing her journey to inspire schoolgirls, these stories break through cynicism and inspire action. Stories have the power to transform hearts and transformed hearts change the world.

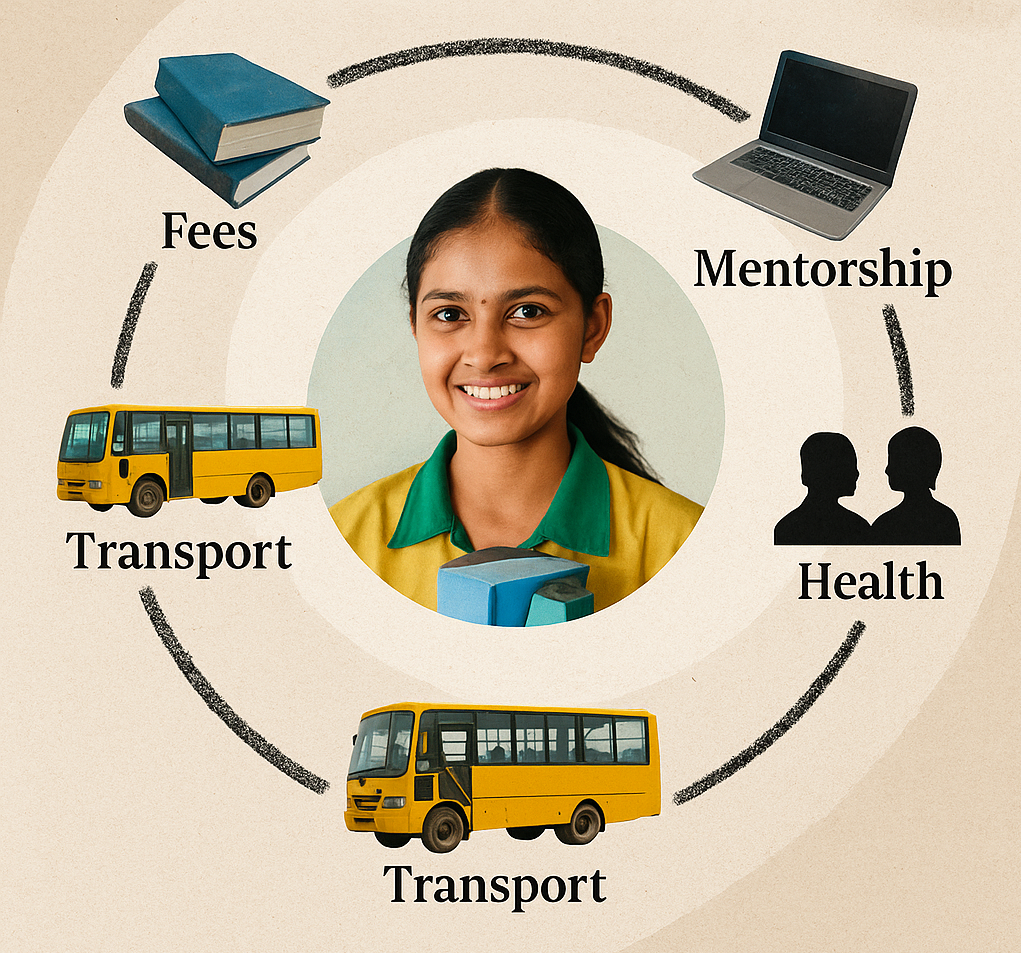

While discussing activism, it’s crucial to highlight that women’s empowerment is not just a political issue, but a social one that touches education, health and economic independence. Empowerment is holistic: a woman who is educated, healthy and financially independent is more likely to participate in politics and community leadership. Recognising this, many organisations in India are working at the grassroots to enable women to stand on their feet and raise their voices. One such initiative is the Swabhiman programme by Smile Foundation – a flagship women’s empowerment program that epitomises the idea of change starting from within communities.

Swabhiman (meaning “self-respect” or “pride”) was launched in 2005 to bridge the very gaps that hold women back, especially in underserved communities. The philosophy is equip women with the resources, knowledge and skills they need to become self-reliant change-makers. This involves ensuring access to education, because knowledge truly is power. The programme helps girls and young women pursue schooling and vocational training – whether it’s computer courses, tailoring or financial literacy – opening up economic opportunities for them.

Economic independence is a game changer for women. When a woman earns her own income, she gains confidence, bargaining power in her family and the freedom to make life choices. Swabhiman focuses on exactly this, helping women get job-ready or start small enterprises so they can support themselves and their families. Over the years, tens of thousands of women have received vocational training through Swabhiman, turning their talents into livelihoods.

Equally important is health and nutrition, an often overlooked facet of empowerment. A woman who is chronically ill or malnourished cannot participate fully in public life. Swabhiman’s community health workers visit neighbourhoods to educate women about reproductive health, maternal care and nutrition. They organise health camps and connect women to medical services, ensuring they and their children stay healthy. This not only improves quality of life but also frees women from the constant worry of illness, allowing them to focus on personal growth and civic engagement. As an example, through health and nutrition counselling, thousands of women have learned about family planning and child healthcare, leading to better outcomes for entire communities.

What’s truly inspiring is how Swabhiman fosters leadership at the grassroots level. The programme forms women’s groups and community networks. Women who once rarely stepped out of their homes are now attending weekly meetings, voicing their concerns and learning to solve problems collectively. They discuss issues like local sanitation, girls’ education or domestic violence, and they approach local authorities as a united front to demand action.

In essence, these women are practising politics at the micro level – getting a taste of advocacy and governance in their own communities. Many have gone on to become community leaders, such as members of school committees or health volunteers, and a few have even contested local elections, emboldened by the confidence and support system they developed.

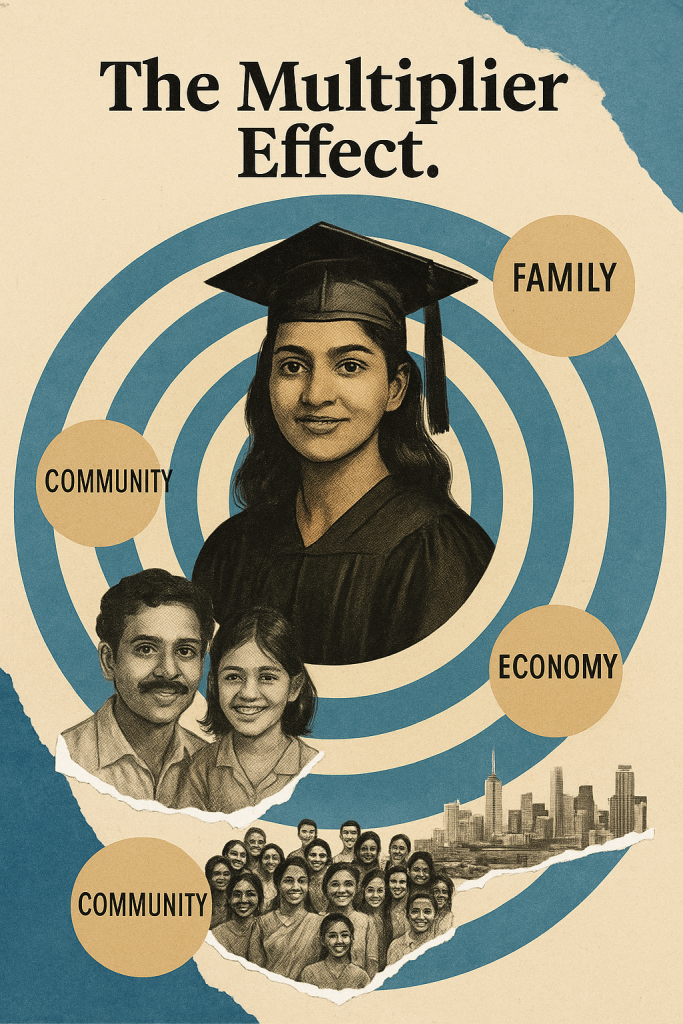

The ripple effects of empowering one woman are immense. Take, for instance, the story of Shyama from Haryana (one of the women highlighted by Swabhiman’s Stories of Change). During the COVID-19 pandemic, Shyama’s husband lost his job and her family was pushed to the brink. Through Swabhiman, Shyama accessed a vocational course in tailoring and was provided initial support to start a small tailoring business at home. She not only earned income to sustain her family through the crisis, but she also gained a newfound confidence.

Today, Shyama trains other village women in stitching and together they’ve formed a self-help group to sell handcrafted garments. Her journey from a housewife with no say in family finances to an entrepreneur and mentor is a testament to what empowerment programmes can achieve. There are countless such stories – of Yashoda in Bengaluru, who used health workshops to become a community health advocate after seeing her family struggle or Ishwati in Maharashtra, who transformed from a daily wage laborer to a savvy small business owner with a micro-loan and training. Each story echoes the truth that when women are given knowledge and opportunity, they uplift not only themselves but everyone around them.

Programmes like Swabhiman illustrate the power of investing in women at the grassroots. They address the interconnected challenges of gender inequality – education gaps, lack of skills, poor health, social norms – in a holistic way. By doing so, they create a pathway to dignity and equality for women who have been on the margins. An educated, skilled, healthy woman with self-confidence is far more likely to assert her rights, participate in local governance or even pursue a political career.

In other words, the seeds of future women leaders are being sown in these community programmes today. The women who learn to raise their voice in a community meeting might tomorrow raise their voice in a state assembly.

These women are living proof that empowerment is not a top-down gift but a bottom-up revolution. When women stand up for themselves, they inevitably stand up for broader social progress, be it in fighting poverty, improving healthcare or demanding justice. We see this in how empowered women invest in their children’s education, campaign against social evils like child marriage and form the backbone of grassroots movements. They are the unsung heroes making daily revolutions in homes and neighbourhoods, which eventually ripple out to transform society.

In conclusion, where do women stand in India? They stand at the forefront of change – as voters, leaders, activists, mothers, workers, dreamers and doers. They stand on the shoulders of the giants who came before (the freedom fighters, the pioneers in politics) and they stand arm-in-arm with each other, forging a path where none existed. India’s socio-political landscape is being slowly reshaped by their hands. Every additional percentage of women voting, every new woman elected to office, every girl who finishes school, every woman who learns a skill and gains confidence – these are the foundation blocks of a more just and equal India.

Women’s participation is growing, their voices getting louder. But the work is far from finished. The halls of power are still largely male, and centuries-old patriarchal attitudes don’t vanish overnight. The promising laws and policies (from reservations in Panchayats to the new Women’s Reservation Bill) now need faithful implementation and societal support. The challenges of proxy power, gender bias and violence must be met with firm resolve and innovative solutions.

Yet, if there is one thing to be optimistic about, it is the indomitable spirit of Indian women. They have shown that they will not be passive or silent. Whether it’s a village woman asserting herself in a Gram Sabha or the women’s movements that have swept urban streets on issues of safety and equality, there is a relentless energy pushing forward. Each generation of women builds on the victories of the last and breaks new ground for the next.

It is the hope that keeps a woman contesting an election she’s told she can’t win, the hope that fuels activists demanding a seat at the table and the hope passed to a young girl that she can be anything she wants – even the Prime Minister. And it is collective action that will turn that hope into reality: action by women and men, by communities and leaders, to ensure women are not just standing, but thriving and leading in every arena of Indian life.

In the final reckoning, empowering women is not a zero-sum game – it uplifts entire families, communities and the nation. As more women take their rightful place in India’s socio-political spaces, India’s democracy itself becomes more vibrant, responsive and just. The road to equality may be long, but with each step taken by strong women (and supportive allies), the destination draws nearer. Where do women stand in India? They stand resolutely on the frontlines of change and if we listen to their voices and support their rise, they will lead India to a brighter, more equitable future for all.

Sources:

- Firstpost – Women in Indian Politics: A story that has changed little over the years

- Indian Express – From 1951-2019: How women voters outnumbered men in Lok Sabha polls

- Indian Express – Govt panel proposes ‘exemplary penalties’ for husband proxies running panchayats

- Drishti IAS – Issue of Pradhan Pati in Panchayats (analysis of proxy leadership in local bodies)

- World Economic Forum – Global Gender Gap Report 2025: Key Findings

- NextIAS Current Affairs – Women’s Political Participation in India (summary of female voter turnout trends)

- Shankar IAS Parliament – Women’s Participation in Politics (historical Lok Sabha representation data and global comparison)

- Hindustan Times – 22 in 1951 to 78 in 2019: How has India fared in electing women? (historical data on women MPs in Lok Sabha)

- Smile Foundation – Women Empowerment Programme – Swabhiman (programme description and impact statistics)